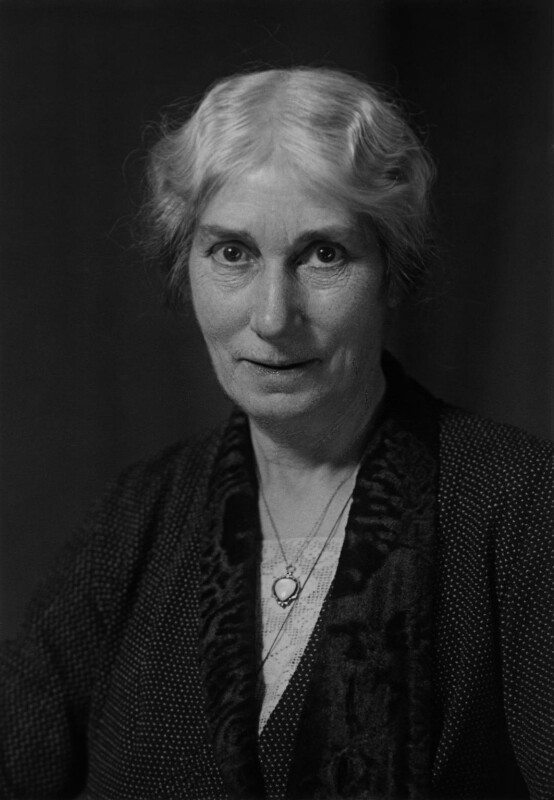

The ninth of Jane Bloyd Sharp and James Sharp’s 11 children, writer and suffragist Evelyn Sharp was born on 4 August 1869. After a year traveling in continental Europe, the Sharp family returned to London and settled in a middle-class neighborhood, later moving to Buckinghamshire. In her autobiography, Unfinished Adventure (1933), Sharp’s childhood memories reflect a frustration with the gendered restrictions placed on her education and play that would inform her later writings for children.

Sharp’s most formational childhood experience, in her own estimation, was attending the progressive Strathallan House girls’ boarding school, which she attended as a day boarder. The separation from her family afforded her both new independence and the opportunity to develop her writing skills. She later would credit the instruction at Strathallan for forming the foundation of her militant suffragist beliefs. Her experiences there also provided the groundwork for her girls school novels, The Making of a School Girl (1897) and The Youngest Girl in the School (1901). After Strathallan, Sharp’s formal education ended. To her enormous frustration, Sharp did not have familial support to pursue a college education, a regret that would continue throughout her life, accompanied by a bitter notation that only her gender precluded her from the experience afforded her brothers ( Unfinished Adventure 40). Her brother, Cecil Sharp (1859-1924), achieved fame as a folk music and dance expert, and shared his sister’s interest and participation in Fabian socialism.

Having left Strathallan at 16, Evelyn Sharp returned to her family’s home for a short time before moving in January 1894 to London, where she took up lodging in Bloomsbury and supported herself by tutoring the orphaned child of architect John D. Sedding. Within the year, she submitted a short story to The Yellow Book and a novel to The Bodley Head, both of which were accepted. Henry Harland (1861-1905), the magazine’s literary editor, and John Lane (1854-1925), its publisher, subsequently introduced her to The Yellow Book writers circle, which would include lifelong friends Laurence Housman (1865-1959), Netta Syrett (1865-1943), William Watson (1858-1935), and Joseph Clayton (1868-1943). The friendships with Housman and Clayton also had connections, through Christian Socialism, to Sharp’s friend and illustrator, Mabel Dearmer (1872-1915). Dearmer illustrated two collections of Sharp’s fairy stories: Wymps and Other Fairy Tales (1897) and All the Way to Fairyland (1898). After meeting fellow Yellow Book contributor and war correspondent Henry W. Nevinson (1856-1841), Sharp embarked on a lifelong love affair with him, though he was married and had multiple other partners. Although not conventional by the bourgeois standards of Edwardian society, the relationship was not unusual among the literary and socialist circles in which the two circulated.

A sharp critic of strict attitudes toward gender and sexuality, Sharp repeatedly centred both her adult fiction and her children’s stories on protagonists’ struggle with and confrontation of social gender expectations, which Sharp portrayed as cruel and marginalizing. Her early writing for The Yellow Book included the story “In Dull Brown” (January 1896), which draws attention to women’s mobility as an advantage, but additionally shows how heterosexual male desire is constructed around a passive and helpless image of femininity. Sharp’s authorial critique extended profoundly into her fiction for children. She depicted child protagonists negotiating punishing constructions around gender, but allowed her characters to confront and dismantle these constructions, which was groundbreaking in fin-de-siècle children’s fiction. Her acquaintance Edward Carpenter (1844-1929) produced critical writing on gender (including transgender, termed “the intermediate sex”), providing an additional framework for Sharp’s own analyses of gender roles and identities. In her story “The Boy Who Looked like a Girl” from her collection Wymps and Other Fairy Tales , Sharp depicts a boy struggling with repeated misgendering as a result of his nursery smock. Certainly influential for Sharp, too, was Carpenter’s 1894 essay “Marriage in a Free Society,” in which he dismisses the possibility of connubial bliss within Victorian England’s gender stratification.

Through her affiliation with the Bodley Head, Sharp briefly came into contact with Oscar Wilde (1854-1900). Although having met Wilde on only two occasions, she, along with many others of The Yellow Book circle, watched his trial for “gross indecency” with horror. In her one autobiographical observation of Wilde, she notes how the trial raised national anxiety about masculinity and male sexuality:

When the Oscar Wilde trial shocked society into an extreme of prudishness never exceeded in the earliest days of the good Queen, one London daily started a shilling cricket fund to which panic-stricken citizens hastened to contribute lest their sexual normality should be doubted—the connection was subtle but felt at the same time to be real—the idea gained ground that the “Yellow Book” had stood in some way or another for everything that was the antithesis of cricket. (Unfinished Adventure 57)

For the rest of her writing career, Sharp’s storytelling drew readers again and again to themes of radical injustice and gender inequality such as she witnessed before, during, and in the wake of Wilde’s trial and incarceration. Her short story “The Little Queen and the Gardener” (1900) begins with Prince Dandytuft being magically punished with field labour in condemnation of his effeminacy. Sharp’s novel The Other Boy (1902) contains a boy obsessed with renouncing the feminine to buoy his own sense of masculinity. Subsequently, he behaves antagonistically toward the “other boy” of the title who is feminine and wishes to pursue a career in the arts. Also combating reductive gender roles are a child called Charley (née Charlotte) who repeatedly expresses the wish to be identified and treated as a boy, and a New Woman governess who arrives by bicycle. Sharp’s stalwart refusal to romanticize children or their experiences differentiated her from many of her contemporaries. Instead, she insisted that “Childhood, at its worst, is unhappy; at best, it is uncomfortable” ( Fairy Tales 1).

During her early years in London, Sharp became increasingly engaged with political activism. She joined the Fabian Society, which espoused a socialist state achieved through reform of existing law rather than outright revolution. Unlike fellow Fabian and children’s book writer E. Nesbit (1858-1924), who expressed concern that suffrage would draw attention away from the broader socialist cause, Sharp made suffrage the keystone of her political agitation. She joined the Women Writers’ Suffrage League. Selling copies of the Women’s Social and Political Union’s Votes for Women and participating in civic disruption led to friendships with writer Beatrice Harraden (1864-1936) and pioneering mathematician and engineer Hertha Ayrton, (1854-1923) whom Sharp later celebrated in a biography, Hertha Ayrton 1854-1923: A Memoir (1926). She brought her writing talents to the cause, producing the short story collection Rebel Women (1910) in order to highlight the diverse lives of suffragettes, rather than the offensive caricatures that dominated the contemporary press.

Concerned about upsetting her family, Sharp initially limited her suffragist work to activities that would avoid arrest or imprisonment. However, after a 1911 letter from her mother acknowledging the need for strident action, Sharp felt at liberty to pursue riskier political demonstrations. Subsequent agitating for the vote led to several imprisonments for Sharp beginning in November 1911, even as she took on an editor position at Votes for Women. By 1915, she directed some of her political resistance to taxes, refusing to pay them on the basis that, without the vote, she was not a citizen and did not believe in taxation without representation. The result was a subsequent period spent in constant movement to avoid arrest and using a network of friends for the purpose of forwarding her mail.

Although the majority of Sharp’s activism focused on suffrage, she also protested the death penalty and advocated pacifism leading up to and throughout World War I. Her socialist and pacifist beliefs infuse the tales in her short story collection The War of All the Ages (1915), which depicts a socialist vicar striving to deal with social reality versus idealism (“The Memorial Service”); civilian deaths as a result of war rationing (“The Casualty”); and tenement poverty (“A Million a Day”). One story, “Our Club,” contains a pointed critique of George Gissing’s women characters. The story’s narrator notes, “Then there is the ‘odd’ woman who might have stepped straight out of Gissing’s imagination, except that she carries a high hope and courage in her frail little body that in Gissing’s women were yet unborn” (56).

By the 1920s, Sharp shifted primarily to producing non-fiction and political pamphlets. She started working in conjunction with Quakers, with whom she shared pacifist principles. Sharp traveled extensively during this time; journeys included trips to Germany, Ireland, and Russia. In addition to her biography of Ayrton, she wrote about humanitarian crises in Russia and Germany and produced work for the Women’s Co-operative Guild.

Finally, in 1933, she wrote her autobiography, the last major literary output of her career. Concurrently, she wrote a libretto for a comic opera, The Poisoned Kiss (1933), with composer Ralph Vaughn Williams, with whom, as with her deceased brother Cecil, she shared an interest in traditional English dance and music. The year also witnessed her marriage to Nevinson (whose wife Margaret died in 1932), with whom Sharp remained until his death in 1941. By 1948, Sharp had taken up residence in a nursing home, where she stayed until her death on 17 June 1955.

© 2019 Amanda Hollander

Amanda Hollander holds a doctorate in Victorian literature from the University of California, Los Angeles. Her essay on Evelyn Sharp and Oscar Wilde was published in Oscar Wilde and the Cultures of Childhood (2017). She is an independent scholar and works as an opera librettist and children’s book writer.

Selected Publications by Evelyn Sharp

- All the Way to Fairyland. The Bodley Head, 1898.

- At the Relton Arms: A Novel. The Bodley Head, 1895.

- “In Dull Brown.” Yellow Book, vol. 8, January 1896, pp. 180-204.

- “The End of an Episode.” Yellow Book, vol. 4, January 1895, pp. 255-74.

- Fairy Tales: As They Are, as They Were, and as They Should Be . D. B. Friend, 1889.

- Here We Go Round: The Story of the Dance. Gerald Howe, 1928.

- “The Little Queen and the Gardener.” Lippincott’s Monthly Magazine , vol. 66, 1900, pp. 938-47.

- The Making of a School Girl. The Bodley Head, 1897.

- “A New Poster.” Yellow Book, vol. 6, July 1895, pp. 123-66.

- The Other Boy. Macmillan, 1902.

- “The Other Anna.” Yellow Book, vol. 13, April 1897, pp. 170-93.

- The Other Side of the Sun. The Bodley Head, 1900.

- Rebel Women. John Lane, 1910.

- “The Restless River.” Yellow Book, vol. 12, January 1897, pp. 167-90.

- Unfinished Adventure: Selected Reminiscences from an Englishwoman’s Life . The Bodley Head, 1933.

- The Victories of Olivia and Other Stories. Macmillan, 1912.

- The War of All the Ages. Sidgwick & Jackson, 1915.

- Wymps and Other Fairy Tales. The Bodley Head, 1897.

- The Youngest Girl in School. Macmillan, 1901.

Selected Publications about Evelyn Sharp

- Green, Barbara J. “Mediating Women: Evelyn Sharp and the Feminist Networks of Suffrage Print Culture.” The History of British Women’s Writing, Volume 7, 1880-1920 , edited by Holly Laird, Palgrave Macmillan, 2016, pp. 72-82.

- Hollander, Amanda. “Oscar Wilde, Evelyn Sharp, and the Politics of Dress and Decoration in the Fin-de-Siècle Fairy Tale.” Oscar Wilde and the Cultures of Childhood, edited by Joseph Bristow, Palgrave Macmillan, 2017, pp. 119-44.

- John, Angela. Evelyn Sharp: Rebel Woman, 1869-1955 . Manchester UP, 2009.

- Ledger, Sally. “Wilde Women and The Yellow Book : The Sexual Politics of Aestheticism and Decadence.” English Literature in Transition, 1880-1920, vol. 50, no. 1, 2007, pp. 5-26.

- Liddington, Jill. Vanishing for the Vote: Suffrage, Citizenship and the Battle for the Census . Manchester UP, 2014.

- Liggins, Emma. Odd Women?: Spinsters, Lesbians and Widows in British Women’s Fiction, 1850s–1930s . Manchester UP, 2014.

- Miller, Jane Eldridge. Rebel Women: Feminism, Modernism and the Educational Novel . Virago, 1994.

- Oakley, Ann. Women, Peace and Welfare: A Suppressed History of Social Reform, 1880-1920 . Bristol UP, 2018.

- Tosi, Laura. “Children’s Literature in No-Land: Utopian Spaces and Gendered Utopias in Evelyn Sharp’s Fairy Tales.” Children’s Books and Child Readers: Constructions of Childhood in English Juvenile Fiction , edited by Christiane Bimberg and Thomas Kullmann, Shaker, 2006, pp. 35-46.

- Windholz, Anne M. “The Women Who Would Be Editor: Ella D’Arcy and the Yellow Book.” Victorian Periodicals Review , vol. 29, no. 2, Summer 1996, pp. 116-30.

MLA citation:

Hollander, Amanda. “Evelyn Sharp (1869-1955),” Y90s Biographies. Yellow Nineties 2.0, edited by Lorraine Janzen Kooistra, Ryerson University Centre for Digital Humanities, 2019, https://1890s.ca/sharp_e_bio/.