THE SAVOY

AN ILLUSTRATED MONTHLY

NO. 4

CHISWICK PRESS:—CHARLES WHITTINGHAM AND CO., TOOKS COURT,

CHANCERY LANE, LONDON.

LITERARY CONTENTS

PAGE

BEAUTY’S

HOUR. A Phantasy By O. SHAKESPEAR. (In

Two

Parts) .

11

WILLIAM BLAKE AND HIS

ILLUSTRATIONS TO THE DIVINE

COMEDY.

II. His Opinions on

Dante. (The Second of Three Articles by

W.B.

YEATS)

. .

. .

. .

. .

. 25

“VENITE,

DESCENDAMUS.” A Poem by ERNEST

DOWSON . .

.

41

TWO FOOLISH HEARTS.

A Scene of Rustic

Life By GEORGE

MORLEY .

45

IN PIOUS

MOOD. A Translation by OSMAN EDWARDS into English Verse

of EMILE VERHAEREN’S Poem

“Pieusement”

.

. .

. . 56

FRIEDRICH

NIETZSCHE—III. (The

Third of Three Articles by

HAVELOCK ELLIS)

.

. .

. .

. .

. .

57

STELLA

MALIGNA. A Poem by ARTHUR SYMONS

. . .

. 64

THE DYING OF FRANCIS

DONNE A Study.

By ERNEST DOWSON

. 66

THREE

SONNETS. (Hawker of Morwenstow.—Mother Ann: Foundress of

the

Shakers.—Münster: A.D. 1534.) By LIONEL JOHNSON .

. . 75

THE GINGERBREAD FAIR AT

VINCENNES. A Colour

Study.

By ARTHUR SYMONS

.

. .

. .

. . .

79

THE SONG OF THE

WOMEN. A Wealden Trio.

By FORD MADOX

HUEFFER

. .

. .

. .

. .

. .

85

DOCTOR AND

PATIENT. An Story by RUDOLF

DIRCKS .

. .

87

A LITERARY

CAUSERIE:—On a Book of

Verses. By ARTHUR

SYMONS .

91

NOTE

. . .

. .

. .

. .

. .

.

94

ART CONTENTS

PAGE

COVER

. . Designed by AUBREY BEARDSLEY

. .

.

1

TITLE

PAGE

. . Designed by AUBREY BEARDSLEY

.

. 5

THE

NOVEL. A Lithograph by T.R. WAY

. .

.

. .

9

DANTE AND

UBERTI. After an unpublished Water-Colour Drawing by

WILLIAM

BLAKE .

. .

. .

. .

. .

27

THE CIRCLE OF

THIEVES. After the rare Engraving by

WILLIAM

BLAKE

. .

. .

. .

. .

. .

. 31

DANTE AND VIRGIL CLIMBING THE

FOOT OF THE MOUNTAIN OF

PURGATORY.

After an

unpublished Water-Colour Drawing by WILLIAM

BLAKE

. 35

DANTE, VIRGIL, AND

STATIUS

After an

unpublished Water-Colour Drawing by WILLIAM

BLAKE .

39

A FRONTISPIECE TO BALZAC’S “LA

FILLE AUX YEUX D’OR.”

A

Wood-Engraving after an unpublished Crayon Drawing by CHARLES

CONDER .

.

. .

. .

. .

. .

. 43

A FAIR AT

CHARTRES. After a Pen-and-Ink Drawing

by JOSEPH

PENNELL 78

A VIGNETTE By WILLIAM T. HORTON

.

. .

. .

. 85

A

CUL-DE-LAMPE By WILLIAM T. HORTON

.

. .

. .

86

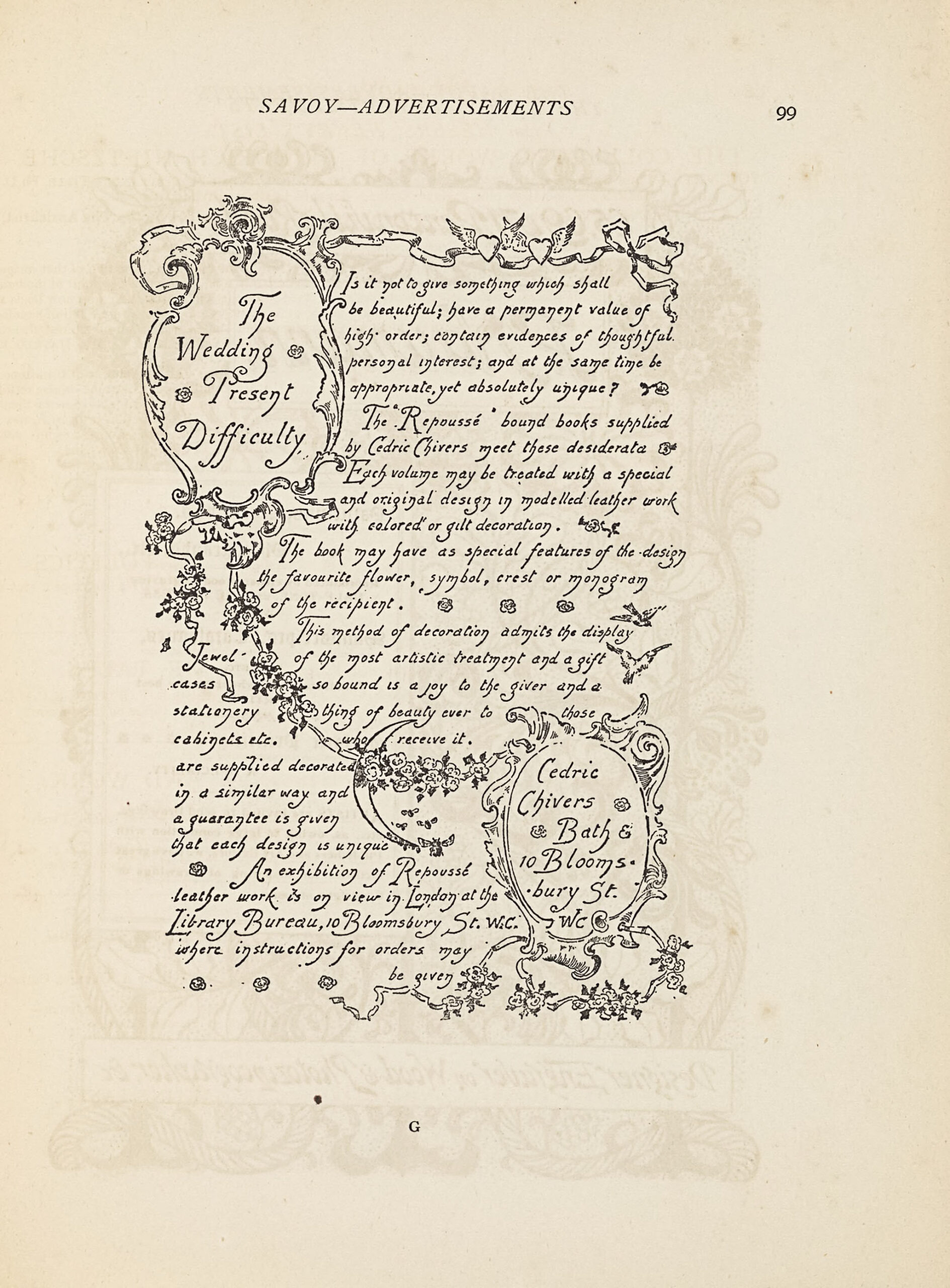

ADVERTISEMENTS . .

. .

. .

. .

. .

. 95

The

Whole of the Reproductions in this Volume, in line and half-tone blocks, and

the

Wood Engraving, are by MR. PAUL

NAUMANN.

BEAUTY’S HOUR

A PHANTASY

CHAPTER I

I REMEMBER very well the first time the strange thing

happened to me : on a winter’s day in January. I reached

home tired, and sat down in front of the looking-glass to

take off my hat ; and remained looking, as I so often do, at

my own unsatisfactory face.

Gerald Harman had come up to his mother’s study

that afternoon, while I was at work after lunch ; ostensibly on business ;

really, because there was a frost which had driven him from Leicestershire

to London, leaving him with nothing to do ; and we had begun talking

of irrelevant matters.

“A woman must be good,” he said reflectively.

“Only a plain woman,” said I. “Who has been behaving ill now?”

“I was generalizing ; or, to be frank, I was thinking of Bella Sturgis.”

“So am I. You surely don’t expect her to possess all the virtues, and

that face ?”

“To be sure, the face is enough,” answered he ; and sat staring full at

me ; but thinking, as I knew, of Bella Sturgis.

“Does she amuse you ?” I asked.

“Amuse me?” said Gerald. “I’m sure I can’t say. One doesn’t think

about being amused when one is with her.”

“She just exists, and that’s enough,” I suggested.

Possibly my voice was ironical ; for Gerald looked at me then, with a

sort of jerk.

“She’s not intellectual, and she’s not really sympathetic, and I don’t like

her one quarter as much as I do you, Mary,” said he.

Now it is an understood thing that he is not to call me Mary ; and so I

reminded him ; but he only answered that we had been over the ground

12 THE SAVOY

before, and that it was time I owned myself defeated. I was beginning to

remark that nothing short of death would induce me to do so, when Lady

Harman came in, and Gerald was somewhat abruptly dismissed.

“I wish that idle, mischievous boy would marry Bella, and settle down,”

said she.

“Yes,” said I, and went on writing.

“Why, Mary, how ill you look!” she cried then. “Is anything the

matter ?”

I hate being told I look ill ; it only means that I look ugly : but I

answered cheerfully, “Nothing in the world ;” and she, being easily satisfied,

went off to another subject, which lasted till it was time for me to go away.

The post of secretary to Lady Harman was not altogether a bed of roses :

she has a wide range of interests, and a soft heart ; but her other faculties are

not quite in proportion. I was generally weary, by the time I reached home,

with the endeavour to reconcile her promises and her practice in the eyes of

the world—that most censorious of worlds, the philanthropic.

I repeated Gerald’s words as I sat before the glass in my bedroom. “To

be sure, the face is enough,” he had said.

My own face, pale, with no salient points to make it even impressively

ugly, gave me back the speech as I uttered it. I have neither eyelashes, nor

distinction ; I do not look clever, or even amiable ; my figure is not worthy

of the name ; and my hands and feet are hopeless.

The concentrated bitterness of years swept over me ; I loved Gerald

Harman, as Bella Sturgis, with her perfect face, was incapable of loving ; but

my love was rendered grotesque by the accident of birth which had made me

an unattractive woman. Given beauty, or even the personal fascination, which

so often persuades one that it is beauty, I could have held my own against

the world, in spite of my poverty, my lack of friends, or of social position.

As things were, I saw myself condemned to a sordid monotony ; ever at a

disadvantage ; cheated of my youth, and of nearly all life’s sweeter possi-

bilities. I was considered clever, by the Harmans, it is true ; but the world

in general, had it noticed me at all, would have refused to believe that such a

face as mine could harbour brains. Gerald, I knew, had proclaimed in the

family that Mary Gower had wits ; and looked on me as his own special

discovery : for though I had but a plain head on my shoulders, it was an

accurate thinking machine ; and could occasionally produce a phrase worthy

of his laughter.

I have a certain dreary sense of humour which prevents my being, as a

BEAUTY’S HOUR 13

rule, quite overwhelmed by this aspect of my life ; but on the January after-

noon of which I write, I was fairly mastered by it ; and when Miss Whateley

came up to light the gas, which she generally did herself, she found me with

my head on the dressing-table, in an attitude of abject despair. Miss Whateley

was my landlady ; and had been my governess in better days.

“My dear,” said she, “what ‘s the matter ?”

“Only my face,” said I.

“Glycerine is the best thing,” said she, and began pulling the curtains.

She knew perfectly well what I meant.

“Whatty,” said I, musingly, “how different my life would be if I were a

pretty woman—though only for a few hours out of the twenty-four.”

“Oh, yes,” she answered. “Yet you might be glad sometimes when the

hours were over.”

I only shook my head ; and fell to looking into my own eyes again,

with the yearning, stronger than it had ever been before, rising like a passion

into my face.

Then something unforeseen happened : Miss Whateley, standing behind

me, saw it ; and I saw it myself as in a dream. My reflected face grew

blurred, and then faded out ; and from the mist there grew a new face, of

wonderful beauty ; the face of my desire. It looked at me from the glass,

and when I tried to speak, its lips moved too. Miss Whateley uttered a

sound that was hardly a cry, and caught me by the shoulder.

“Mary—Mary—” she said.

I got up then and faced her ; she was white as death, and her eyes

were almost vacant with terror.

“What has happened ?” said I.

My voice was the same ; but when I glanced down at my body, I saw

that it also had undergone transformation. It struck me, in the midst of my

immense surprise, as being curious that I should not be afraid. No explana-

tion of the miracle offered itself to me ; none seemed necessary : an effort of

will had conquered the power of my material conditions, and I controlled

them ; my body fitted to my soul at last.

“I’m going mad !” cried poor Miss Whateley.

“We can’t both be mad,” said I. “Don’t be afraid ; tell me what I look

like.”

“You are perfectly beautiful,” she gasped.

I began walking up and down the room : I was much taller, and my

dress hung clear of my ankles ; when I noticed that, I began to laugh.

14 THE SAVOY

“Whatty, I’ve grown,” I cried out.

She sat down. “Do you feel strange ?” she asked.

“Just the same ; only a little larger for my clothes. What are we going

to do ? Will it last ?”

“I think you had better just sit down again, and wish yourself back.”

“Never, never. If beautiful I can be, beautiful I will remain. Let us

put down the hour and the date.”

I took up my diary, and made a great cross against the day ; then

I noticed that the sun set at twenty-seven minutes past four ; it was now

twenty-five minutes to five.

“I wonder what we can do to prove to ourselves that we’ve not been

dreaming, if I go back again ?” I questioned.

“Let us first spend the evening as usual,” answered Miss Whateley.

“I will tell Jane that you are out, and that a young lady is coming to supper

with me.”

Jane was our one servant : her powers of observation were limited ; and

we did not think it would be difficult to deceive her. So the stranger, whose

appearance seemed to bereave her of even her usual small allowance of

sense, sat that night at Miss Whateley’s table ; at ten o’clock we slipped up to

my bedroom ; and when Jane’s tread was heard in the room above, we

breathed freely.

“She’s gone to bed,” said I. “Now we can brew tea, and keep ourselves

awake. We must not sleep ; that is imperative.”

We did not sleep ; though to poor Miss Whateley, who had no sense of a

triumphant new personality to sustain her, the task must have been difficult.

Then, suddenly, at the hour of sunrise, I felt a sensation as of being in

darkness, in thick cloud ; from which I emerged with my beauty fallen from

me like a garment.

We neither of us said anything. I was conscious only of a physical

craving for rest and sleep, which overpowered me : I think Miss Whateley

was struck dumb in the presence of a wonder she could not understand. We

kissed one another silently ; and I went to bed and slept for a couple of hours,

a dreamless sleep.

BEAUTY’S HOUR 15

CHAPTER II

When I reached Lady Harman’s that morning, I found the two girls, Clara

and Betty, alone in their mother’s study.

Betty, with the face of a Romney, and the manners of an engaging child,

is wholly attractive : Clara is handsome too ; she rather affects a friendship

with me on intellectual grounds, which bores me : her theories are the terror

of my life, being always in direct opposition to my own, for which I have to

try and account.

But on this particular morning she had nothing more momentous on her

mind than a dance, which her mother was giving the next evening.

“You must come to it,” Betty cried. “It will be such fun talking it over

afterwards. Onlookers always see most of the game, you know.”

“You are very kind, Betty,” I said. They had long ago insisted that I

should call them by their Christian names. “Has it ever struck you that

onlookers would sometimes like to be in the game, instead of outside it ?”

Betty looked a little confused.

“Well, somebody must look on,” said she. “And it’s lucky when they

see how funny things are ; as you always do, Mary.”

“Is there any particular game going on just now ?” I inquired. “Can I

be of any use ?”

“There’s Bella,” said both girls.

I was very anxious to know the precise sum of Bella’s iniquities. I

shoved away my papers with an entire lack of conscience ; and sat expectant.

“Of course Bella is very young,” Clara began : she being about twenty-

one herself. “One mustn’t judge her too hardly.”

“Has she been doing anything you would not have done yourself?” I asked.

Betty looked at me, and raised her eyebrows. Clara was apt to pose as an

example to her younger sister.

“Well,” said Clara, “if I were engaged to someone as nice as Gerald, and

handsome, and well off, and all the rest of it, I don’t think I’d encourage a little

wretch like Mr. Trench.”

Clara’s social ethics are of a wonderful simplicity.

“Because you’d think it wrong ?” I suggested.

“Well—so silly,” said Clara.

“I think Bella has a perfect right to do as she likes,” broke in Betty.

16 THE SAVOY

“She ‘s not engaged to Gerald ; he hasn’t proposed to her ; and he ought to, for

she ‘s awfully fond of him.”

“I agree with you both,” said I. “Miss Sturgis is silly, but not altogether

to be blamed. Am I to observe her and Mr. Trench together, and report the

phases of the flirtation to you ?”

Yes : that was what they wanted.

“Do you seriously think I’m coming to your dance ?” I went on. “Why,

I haven’t got a dress, or a face fit to show in a ball-room ; and I’ve not been to

a ball for years.”

They fought this statement inch by inch : they would lend me a dress ;

my face didn’t matter ; and after all, I was only twenty-eight, not really old.

I ended the discussion by promising to go ; for an idea had flashed into my

mind, that made me dizzy.

Supposing the other, the beautiful Mary, renewed her existence again that

evening, might she not enjoy a strange, a brief triumph? Would there not be a

perfect, though a secret pleasure in seeing the look in Gerald Harman’s eyes,

in surprising the altered tones of his voice? For beauty drew him like a

magnet.

I fell into such a deep silence over this thought, that Clara and Betty grew

weary, and went away ; and I did not see them again till luncheon-time.

There were three visitors : the man who was in love with Betty, and the

man with whom Betty was in love ; the juxtaposition of the two always

delighted me : I don’t believe they hated one another ; but each believing him-

self to be the favoured lover, had a fine scorn for the other’s folly. The third

guest was Bella Sturgis.

Gerald sat at the end of the table, opposite his mother. As I have said,

the frost kept him from hunting, and he was disconsolate. With him, as with

many finely bred, finely tempered Englishmen, sport was a passion ; more,

a religion. He put into his hunting, his shooting, his cricket, all the ardour,

all the sincerity that are necessary to achievement : I respected this in him,

even while it moved me to a kind of pity ; for I felt instinctively that though

he might have skill and courage to overcome physical difficulties or danger, he

was totally unfitted to cope with the more subtile side of life ; and would be

helpless in the face of an emotional difficulty. On this day of which I write,

he was evidently suffering from some jar to the even tenour of his life ; of which

the continued frost was a merely superficial aggravation.

By his side sat Bella Sturgis : I looked at her with a more critical eye than

usual : she had a great air of languid distinction ; everything about her was

BEAUTY’S HOUR 17

perfect ; from the pose of her head to the intonation of her voice. She very

rarely looked at me, and I don’t think she had ever clearly realized who I was :

I felt sure Gerald had not imparted his discoveries to her with regard to my

wits. I never spoke at luncheon when she was there.

But to-day, the memory of that face in the glass the night before, made me

reckless and audacious.

“I’ve been constituted the girl’s special reporter to-morrow night,” said I

to Gerald. ” I am to observe the faces, and the flirtations.”

“Then you may constitute yourself my special reporter too,” said he,

gloomily.

“It will be the next best thing to dancing,” I went on.

“Why don’t you dance ?” Miss Sturgis asked, lifting her eyes, and

looking at me for an instant.

I confess I was a little surprised at the cleverness of her thrust

“Because nobody asks me,” I said, with a smile.

My candour had no effect on her : she turned to Gerald with an air that

dismissed the whole subject. I noticed that he would hardly answer her ; and

I supposed that the breach between them had widened. So she addressed her-

self to the man with whom Betty was in love ; thereby throwing the table into

a state of suppressed agitation ; with the exception of Lady Harman, who

professed to notice none of the details of domestic life : she left such things to

the girls, or the servants ; and devoted herself to the care of people in Billings-

gate, or in the Tropics, who had need of her, she said. But she was really kind ;

and always had a joint for lunch, “because it was Mary’s dinner ;” and though

I often yearned for the other more interesting dishes, I never dared to suggest

any deviation from beef and mutton : to-day it was mutton.

“Won’t you have some more ?” said Lady Harman. “I can’t help

thinking how much we waste. Some of my poor families would be so glad of

this, and here ‘s only Mary touches it.”

“Oh, mother,” said Betty, “your poor people are always starving ; and a leg

more or less wouldn’t make much difference.”

“What ‘s an arm or a leg, compared with a face ?” said the young man who

was in love with Betty, with his eyes fixed on her. His remark had no direct

bearing on the subject, which he had but half followed ; and it sent her into

a fit of suppressed laughter, with which Clara remonstrated in an under-

tone.

“I don’t care,” said the rebellious Betty. “It ‘s Gerald’s house, and as

long as he doesn’t mind my giggling, I shall giggle.”

18 THE SAVOY

“I mind nothing,” said the master of the house. His mood was obviously

overcast. I saw Bella throw a look at him out of her deep eyes ; the eyes of

a woman who has always lived under emotional conditions. I began to realize

dimly what such conditions might be like.

He got up, and pushed his chair from the table.

“Will you excuse me,” said he. “I have an engagement.”

“Do go,” said Lady Harman, “you are always late, Gerald. I’m sure you

ought to go at once.”

Bella held out her hand to him.

“It ‘s au revoir, not good-bye,” said he, and did not take it.

That evening my transformation took place again ; under the same con-

ditions of ardent desire on my part.

“To-morrow,” said I to Miss Whateley, “I shall go to the Harman’s ball

in the character of Mary Hatherley.” Hatherley had been my mother’s maiden

name.

“But you have no dress,” said Miss Whateley. “And how can you

account for yourself?”

“I must do it,” I cried. “You must think of some plan.”

“Let us go,” said she, “to Dr. Trefusis.”

CHAPTER III

Dr. Trefusis was the only man who had ever loved me. He was my

father’s great friend ; but I feel sure he must once have been in love with my

mother ; at least, I can only account for his great affection for myself, on some

such sentimental hypothesis. When my father died, four years ago, and I

was involved in money difficulties, it was Dr. Trefusis who took me in, and

eventually got me my secretaryship with Lady Harman. He wanted me to

share his home ; but this I refused to do ; believing that his affection for me

would not stand the test of losing his liberty, and his solitude.

When we reached his house, he was out ; and we waited some time in the

library.

“He won’t believe us,” Miss Whateley kept saying ; and this seemed so

likely, that I was shivering with nervousness when he at last came in.

“You won’t believe it,” said Miss Whateley, “but this is Mary Gower.”

BEAUTY’S HOUR 19

He looked very blank ; but recovering his presence of mind, turned to me

and said,

“A cousin, I presume, of my old friend, Mary Gower ?”

“Oh, Dr. Trefusis,” cried I, “we have come to you with the most extra-

ordinary story : don’t you know my voice ? I am Mary ; but I have got into

another body.”

“The voice is Mary’s,” said he, in the tone of one balancing evidence.

Then Miss Whateley began telling him what had happened : while I sat

in silence, watching the mixture of wonder and scepticism on his face. I

noticed also another look, when his eyes met mine, a look that was almost

devout—he had always been a worshipper of beauty.

When the story was done, he began asking questions : my answers seemed

unsatisfactory : we sat at last without speaking, while he looked at me, and

drummed on the table.

“You are very plausible people,” he said, at length ; “but you can’t expect

me to believe all this ; though I’m at a loss to imagine why you should take

the trouble to play such a practical joke on a poor old fellow like myself.

Still, I’ll not be ungracious, and grumble ; for it has given me a great deal of

pleasure to see anything so charming in this dull place.”

He got up, as though he wished to end the interview.

I was in despair : his determination not to recognize me struck like a

blow at my sense of identity : then the thought came : could I, by a supreme

effort of will, induce a transformation under his very eyes ?

I held out my right hand—long and beautiful ; with delicate fingers, that

yet were full of nervous strength.

“That,” said I, “is not the hand of Mary Gower.” He shrugged his

shoulders.

“It is not,” said he.

“Look at it,” I cried.

Then came an awful moment during which I concentrated my whole will

in a passion of energy ; the room went black ; I was dimly conscious that Dr.

Trefusis had fallen on his knees by the table ; and was watching the hand I

held under the lamp, with suspended breath : for it had begun to change ;

some subtile difference passed over it, like a cloud over the face of the sun :

its beauty of line and colour faded ; the long fingers shrunk, and widened ; the

blue-veined whiteness darkened into a coarser tint ; the fine nails lost their

shape, and grew ugly, stunted, and opaque.

Dr. Trefusis spoke no word : I felt his fingers were ice-cold as he turned

20 THE SAVOY

up my sleeve, and noted how the coarsened wrist grew into the perfect arm ;

he held my hand, and swung it to and fro ; then he left the room abruptly,

saying “don’t move.”

I sat still at the table : Miss Whateley came and stood by me.

“Mary,” she said, “it must be wrong ; it is playing with some terrible

power you don’t understand.”

“Probably we’ve all got it,” I answered dreamily. “It is perhaps a spark

of the creative force—but Dr. Trefusis and all his science won’t be able to

explain it.”

Then the doctor came back, with instruments, and microscopes, and I

know not what, and began to examine the miracle. At last he looked

up at me.

“I can make nothing of it,” said he. “But it is the hand of Mary Gower.

That is beyond dispute. Now let it go back.”

He held it in his own : this time the change was quicker ; and he dropped

it with a shudder.

“Now do you believe me ?” I asked.

He answered, “yes ;” and sat lost in thought.

“You had better go home now,” he said presently. “I must think over

all this ; there must be some hypothesis—miracles don’t happen—you must let

me see you every day.”

I never have understood, and never shall understand, the scientific theories

which he had first built up, in order to account for what had happened to me.

I was grateful for the curiosity and interest that my case roused in him,

because they led him to help me in practical ways ; but any attempt at

a scientific explanation of the mystery struck me as being irrelevant, and not

particularly interesting. This attitude on my part at once amused, and

irritated him ; he gave up trying to make me understand the meaning of his

investigations ; and of the experiments which he made me try ; for it was not

till later, that he came to look upon the matter as beyond any scientific solu-

tion ; and only to be accounted for on grounds which he would at first have

rejected with scorn.

I pass these things over ; because I could not write of them intelligibly,

and I might be doing Dr. Trefusis some injustice by an imperfect exposition.

On this occasion, I burst in suddenly, and scattered his reflections by

declaring that I must go to the Harman’s ball the next night, in my new

character.

The idea seemed to divert him.

BEAUTY’S HOUR 21

“Ha !” said he. “Mary Gower wants to taste the sweets of success,

does she ! Upon my soul, it would be worth seeing you, my dear. But

it would be difficult to account for the sudden rising of such a star.”

“Not if you took me, and chaperoned, and uncled me,” I said.

He took a turn or two in the room.

“Why not ?” he said then, with a laugh.

“Oh, Dr. Trefusis, would you really !” I cried out, and seized him by

both hands.

He held them and looked at me oddly ; he is a man of nearly sixty, and

my old friend ; so I could not be angry when he bent down and kissed me.

“I would do anything for a pretty woman,” said he.

I felt a sudden pang : this was the first tribute offered to my beauty,

and it hurt. Was Mary Gower beginning already to be jealous of Mary

Hatherley ?

We settled the matter, with jests and laughter. Dr. Trefusis has the

spirit of a child, and the capacity for making abrupt transitions from the

serious to the absurd ; and he now entered into the plot as though it were

a game ; as though nothing had happened to unnerve and startle him but

a short time before. I was to be his niece, a niece from the country ; if further

inquiries were made, and my non-appearance during the day had to be

accounted for, I was to be a devoted art student ; an eccentric ; who gave her

days to painting, and her evenings to pleasure. Miss Whateley’s faint

objections were soon silenced : we parted with a promise to meet the next

morning ; when the Harman household would be upset and I should not

be wanted ; to choose a ball dress.

“Not that that face of yours needs any artificial setting,” were his last

words.

“I only hope you won’t repent all this,” were Miss Whateley’s, as

we went up to bed.

CHAPTER IV

My father had taken me, as a young girl, to balls: I had sat out unnoticed,

but observant ; and it had seemed to me that, under apparently artificial con-

ditions, women grouped themselves into three distinct types ; which were

almost primitive in their lack of complexity. The beauty ; the woman

whose claims to beauty are not universally acknowledged ; and the plain

woman.

22 THE SAVOY

The beauty always pleased me the most: she was unconscious; using her

divine right of sovereignty with a carelessness only possible to one born in the

purple ; experience had bred in her a certainty of pleasing that made her

indifferent to the effect she produced ; which indifference made her the more

effective. That she had her secret moments of scorn, I never doubted ; a scorn

of that lust of the eye which held her beauty too dear ; and I wondered

whether any such woman had ever felt tempted in some moment of outraged

emotion, to curse the loveliness that men loved, careless of the heart, or head.

The woman with disputable claims annoyed me : she seemed to me like

a queen dependent on the humour of the mob, from whose brows the uneasy

crown might be torn, and trampled under foot ; and then replaced at a caprice.

She was uncertain of herself; too much affected by the opinions of others to be

easy or unconscious. I was sorry for her too; I felt sure that she often married

the man who thought her beautiful, out of gratitude ; for she was always

unduly grateful ; her attitude towards the world being one of mingled

depreciation and assertion.

As for the plain woman, had I not stood hand in hand with her outside

the gates of Paradise all my life, the angel with the two-edged sword looking

on us, with eyes that held both pity and satire ! Oh, kind angel—stand aside,

and let us look through the bars, and see gracious figures going to and fro ;

and listen to strange music, and to the sound of voices moved by a keen,

sweet passion. We look ; we fall back ; and know the angel by his several

names : Fate : Injustice : Mercy.

I had always recognized the subtile emotional intoxicant that is distilled

from the atmosphere of a ball-room. It seemed to come in great waves about

me, as I walked up the Harman’s ball-room, followed by Dr. Trefusis.

He had written for permission to bring his niece, and they were prepared

to see me. No, I am wrong ; they were not prepared. Lady Harman was

visibly taken aback ; and Clara and Betty had something deferential in their

manner, which showed a desire to be unusually pleasing. Then Gerald came

forward. His eyes met mine, with the look of one who sees something he has

long sought, and despaired of finding.

“Can you spare me a dance—” he asked, pausing at the name.

“My name is Hatherley,” said I.

My voice struck him ; he glanced at me with a puzzled expression, and

hesitated—for a moment.

“I must have more than one,” he said.

BEAUTY’S HOUR 21

That was so like Gerald, I nearly laughed.

“The page is blank, you see,” I answered.

He took advantage of my remark, and wrote his name several times in

my programme. I have the programme still.

Dancing had begun again : a crowd had emerged from the stairs

and the anterooms. A number of men were introduced to me ; some of

whom I had already seen at the house. The first with whom I danced was a

Colonel Weston ; I knew him, on Betty’s authority, to be a beautiful dancer,

but he was a head shorter than I, and I smiled involuntarily when he said,

“Shall we dance ?”

He caught my smile.

“Why are you so divinely tall, O daughter of the gods ?” said he.

“And from what Olympian height have you descended this evening? Why

have I never met you before ?”

“I will answer no questions,” said I, “till we have danced. My feet ache

to begin.”

“Then they don’t dance on Olympus ?”

“The gods must come among the mortals to make merry,” I said.

“For which thing let us be thankful,” he answered. Then we moved

away : I had been hitherto a bad dancer, but to-night I felt a spirit in my

feet ; and realized, for the first time, the mysterious joy of perfect motion. As

we paused near the door, I saw Bella Sturgis coming slowly up the stairs.

She did not take her eyes off me ; I saw her question the man on whose arm

she was leaning ; but he looked at me, without answering. It was a revelation,

that look in their eyes ; I saw it repeated, in other faces, over and over again,

as I walked slowly across the ball-room after the dance was over.

The next was with Gerald : my pulses beat thickly, and I was hardly

conscious of the outside world, till we stopped dancing, and he led me into a

little room, which I did not at the moment recognize as Lady Harman’s study.

“And so I have met you at last,” he said ; and I asked him what he

meant.

“Yours is the face I have been looking for all my life,” he answered.

There was a strange simplicity in his voice, and words ; as though he spoke

on an impulse that overruled all conventions, all fear of offence.

“But what of the woman behind the face ?” I questioned.

“Can I ever hope to know her ?”

“If you know her, you will be disappointed : she is like any other

woman.”

24 THE SAVOY

He shook his head.

“I don’t believe it. Tell me what she is really like.”

I looked round vaguely, my thoughts intent on what I should say to him :

then I suddenly noticed the pictures on the walls, and remembered that this

was the room in which Mary Gower sat every day.

“She is not without heart, and she has a head that can think,” said I.

“That is not like every other woman.”

“Would you credit her with either, if she had another face ?” I asked him.

Something in my voice struck him, for the second time ; he looked at

me, with a quickened attention.

“The face is an indication of the soul, surely,” he answered.

“That is a lie,” said I. “A lie invented to cover the injustice done alike

to the beautiful woman, and the woman who is not beautiful.”

“Injustice ?” he echoed.

“The thing is so simple,” said I, with a bitterness I could not hide.

“You place beauty on a pedestal ; her face is an index to her soul, you say :

what happens if you find she does not possess the soul, which she never claimed

to have, but which you insisted on crediting her with ? You dethrone her

with ignominy. The case of the other woman is as hard : she has a face that

does not attract you, so you deny her the soul that you forced on the other

one. She goes through life, branded ; not by individuals, I allow, but by

public opinion. The vox populi is the voice of nature, ’tis true ; but nature is

very hard, very ruthless.”

I stopped : Gerald sat looking at me, with a rapt gaze, but I saw he had

not listened to a word I said. The Hungarian band had begun playing again

in the ball-room. As I listened, and watched the phantastic whirl of the dancers

through the open door, they seemed to me to symbolize the burden of all the

ages : desire and satiety ; illusion and reality ; dancing hand in hand, to a

music wild and tender as love ; sad and stern as life : partners that look ever

in one another’s eyes, and dance on, in despite of what they see.

“Let us go and dance too,” said Gerald.

I have no very clear recollection of the rest of that evening : there was

unreality in the air, and a glamour, and an aching pain. Men and women said

gracious things to me ; yet seemed to watch me with cruel faces ; I was only

conscious, at the last, of an imperative desire to fly, to hide myself, to escape

even from Gerald’s presence ; and to be alone.

O. SHAKESPEAR.

( To be continued.)

WILLIAM BLAKE AND HIS ILLUSTRATIONS TO THE DIVINE COMEDY

II. HIS OPINIONS ON DANTE

AS Blake sat bent over the great drawing-book, in which he

made his designs to “The Divine Comedy,” he was very

certain that he

and Dante represented spiritual states which

face one another in an eternal enmity.

Dante, because a

great poet, was “inspired by the Holy Ghost” ; but his

inspiration was mingled with a certain philosophy, blown

up out of his age, which

Blake held for mortal and the enemy of immortal

things, and which from the

earliest times has sat in high places and ruled the

world. This philosophy was the

philosophy of soldiers, of men of the world,

of priests busy with government, of

all who, because of their absorption in

active life, have been persuaded to judge

and to punish ; and partly also,

he admitted, the philosophy of Christ ; who, in

descending into the world, had

to take on the world ; who, in being born of Mary,

a symbol of the law in

Blake’s symbolic language, had to ” take after his mother,”

and drive the

money-changers out of the Temple. Opposed to this was another

philosophy,

not made by men of action, drudges of time and space, but by Christ

when

wrapped in the divine essence, and by artists and poets, who are taught by

the

nature of their craft to sympathize with all living things, and who, the more

pure and fragrant is their lamp, pass the further from all limitations, to come

at last to forget good and evil in an absorbing vision of the happy and the

unhappy. The one philosophy was worldly, and established for the ordering

of the

body and the fallen will, and, so long as it did not call its “laws of

prudence”

“the laws of God,” was a necessity, because “you cannot have

liberty in this world

without what you call moral virtue” ; the other was

divine, and established for

the peace of the imagination and the unfallen will,

and, even when obeyed with a

too literal reverence, could make men sin against

no higher principality than

prudence. He called the followers of the first

26 THE SAVOY

philosophy pagans, no matter by what name they knew themselves ; because

the

pagans, as he understood the word pagan, believed more in the outward

life, and in

what he called “war, princedom, and victory,” than in the secret

life of the

spirit : and the followers of the second philosophy Christians,

because only those

whose sympathies had been enlarged and instructed by

art and poetry could obey the

Christian command of unlimited forgiveness.

Blake had already found this “pagan”

philosophy in Swedenborg, in Milton,

in Wordsworth, in Sir Joshua Reynolds, in many

persons, and it had

roused him so constantly and to such angry paradox, that its

overthrow

became the signal passion of his life, and filled all he did and thought

with the excitement of a supreme issue. Its kingdom was bound to grow

weaker

so soon as life began to lose a little in crude passion and naive

tumult ; but

Blake was the first to announce its successor, and he did

this, as must needs be

with revolutionists who also have “the law” for

“mother,” with so firm a

conviction that the things his opponents held white

were indeed black, and the

things they held black indeed white ; with so strong

a persuasion that all busy

with government are men of darkness and “some-

thing other than human life” ; with

such a fluctuating fire of stormy paradox,

that his phrases seem at times to

foreshadow those French mystics who have

taken upon their shoulders the overcoming

of all existing things, and say

their prayers “to Lucifer, son of the morning,

derided of priests and of kings.”

The kingdom that was passing was, he held, the

kingdom of the Tree of

Knowledge ; the kingdom that was coming was the kingdom of

the Tree of

Life : men who ate from the Tree of Knowledge wasted their days in

anger

against one another, and in taking one another captive in great nets ; men

who sought their food among the green leaves of the Tree of Life condemned

none but the unimaginative and the idle, and those who forget that even

love and

death and old age are an imaginative art.

In these opposing kingdoms is the explanation of the petulant

sayings he

wrote on the margins of the great sketch-book, and of those

others, still more

petulant, which Crabb Robinson has treasured in his diary. The

sayings about

the forgiveness of sins have no need of further explanation, and are

in contrast

with the attitude of that excellent commentator, Herr Hettinger, who,

though

Dante swooned from pity at the tale of Francesca, will only “sympathize”

with

her “to a certain extent,” being taken in a theological net. “It seems as if

Dante,” Blake wrote, “supposes God was something superior to the Father of

Jesus ; for if he gives rain to the evil and the good, and his sun to the just and

the unjust, he can never have builded Dante’s Hell, nor the Hell of the Bible,

BLAKE’S ILLUSTRATIONS TO THE DIVINE COMEDY 29

as our parsons explain it. It must have been framed by the dark spirit itself,

and so I understand it.” And again, “Whatever task is of vengeance and

whatever

is against forgiveness of sin is not of the Father but of Satan, the

accuser,

the father of Hell.” And again, and this time to Crabb Robinson,

“Dante saw

devils where I saw none. I see good only.” “I have never

known a very bad man

who had not something very good about him.”

This forgiveness was not the

forgiveness of the theologian who has received a

commandment from afar off; but

of the mystical artist-legislator who believes

he has been taught, in a

mystical vision, that “the imagination is the man him-

self,” and believes he

has discovered in the practice of his art, that without a

perfect sympathy

there is no perfect imagination, and therefore no perfect life.

At another

moment he called Dante, “an atheist, a mere politician busied

about this world,

as Milton was, till, in his old age, he returned to God whom

he had had in his

childhood.” “Everything is atheism,” he had already

explained, “which assumes

the reality of the natural and unspiritual world.”

Dante, he held, assumed its

reality when he made obedience to its laws

the condition of man’s happiness

hereafter, and he set Swedenborg beside

Dante in misbelief for calling Nature,

“the ultimate of Heaven,” a lowest rung,

as it were, of Jacob’s ladder, instead

of a net woven by Satan to entangle

our wandering joys and bring our hearts

into captivity. There are certain

curious unfinished diagrams scattered here

and there among the now separated

pages of the sketch-book, and of these there

is one which, had it had all its

concentric rings filled with names, would have

been a systematic exposition of

his animosities, and of their various

intensity. It represents Paradise, and in

the midst, where Dante emerges from

the earthly Paradise, is written,

“Homer,” and in the next circle,

“Swedenborg,” and on the margin these

words : “Everything in Dante’s Paradise

shows that he has made the earth the

foundation of all, and its goddess Nature,

memory,” memory of sensation, “not

the Holy Ghost. . . . Round Purgatory is

Paradise, and round Paradise

vacuum. Homer is the centre of all, I mean the

poetry of the heathen.” The

statement that round Paradise is vacuum is a proof

of the persistence of his

ideas and of his curiously literal understanding of

his own symbols ; for

it is but another form of the charge made against Milton

many years

before in “The Marriage of Heaven and Hell.” “In Milton the Father

is

destiny, the son a ratio of the five senses,” Blake’s definition of the

reason

which is the enemy of the imagination, “and the Holy Ghost vacuum.”

Dante, like the Kabalists, symbolized the highest order of created beings by

the

fixed stars, and God by the darkness beyond them, the Primum

Mobile.

30 THE SAVOY

Blake, absorbed in his very different vision, in which God took always a human

shape, believed that to think of God under a symbol drawn from the outer

world

was in itself idolatry ; but that to imagine Him as an unpeopled im-

mensity

was to think of Him under the one symbol furthest from His essence;

it being a

creation of the ruining reason, “generalizing” away ” the minute

particulars of

life.” Instead of seeking God in the deserts of time and space, in

exterior

immensities, in what he called “the abstract void,” he believed that the

further he dropped behind him memory of time and space, reason builded

upon

sensation, morality founded for the ordering of the world ; and the more

he was

absorbed in emotion ; and, above all, in emotion escaped from the impulse

of

bodily longing and the restraints of bodily reason, in artistic emotion ; the

nearer did he come to Eden’s “breathing garden,” to use his beautiful phrase,

and to the unveiled face of God. No worthy symbol of God existed but the

inner

world, the true humanity, to whose various aspects he gave many names,

“Jerusalem,” “Liberty,” “Eden,” “The Divine Vision,” “The Body of God,”

“The

Human Form Divine,” “The Divine Members,” and whose most intimate

expression

was Art and Poetry. He always sang of God under this symbol :

For Mercy, Pity, Peace, and Love

Is God Our Father dear ;

And Mercy, Pity, Peace, and Love

Is man, His child and care.

For Mercy has a human heart ;

Pity a human face ;

And Love, the human form divine,

And Peace, the human dress.

Then every man of every clime,

That prays in his distress,

Prays to the human form divine—

Love, Mercy, Pity, Peace.

Whenever he gave this symbol a habitation in space he set it in the sun, the

father of light and life ; and set in the darkness beyond the stars, where light

and life die away, Og and Anak and the giants that were of old, and the

iron throne of Satan.

By thus contrasting Blake and Dante by the light of Blake’s

paradoxical

wisdom, and as though there was no great truth hung from

Dante’s beam of

the balance, I but seek to interpret a little-understood

philosophy rather

than one incorporate in the thought and habits of

Christendom. Every

philosophy has half its truth from times and generations ;

and to us one half

BLAKE’S ILLUSTRATIONS TO THE DIVINE COMEDY 33

of the philosophy of Dante is less living than his poetry ; while the truth

Blake preached, and sang, and painted, is the root of the cultivated life, of the

fragile perfect blossom of the world born in ages of leisure and peace, and

never yet to last more than a little season ; the life those

Phæacians—who told

Odysseus that they had set their hearts in

nothing but in “the dance, and

changes of raiment, and love and

sleep”—lived before Poseidon heaped a

mountain above them ; the lives of

all who, having eaten of the tree of life,

love, more than the barbarous ages

when none had time to live, “the minute

particulars of life,” the little

fragments of space and time, which are wholly

flooded by beautiful emotion

because they are so little they are hardly of

time and space at all. “Every

space smaller than a globule of man’s blood,”

he wrote, “opens into eternity of

which this vegetable earth is but a shadow.”

And again, “Every time less than a

pulsation of the artery is equal in its

tenor and value to six thousand years,

for in this period the poet’s work is

done, and all the great events of time

start forth, and are conceived : in such a

period, within a moment, a pulsation

of the artery.” Dante, indeed, taught,

in the “Purgatorio,” that sin and virtue

are alike from love, and that love is

from God ; but this love he would

restrain by a complex external law, a

complex external Church. Blake, upon the

other hand, cried scorn upon the

whole spectacle of external things, a vision

to pass away in a moment, and

preached the cultivated life, the internal Church

which has no laws but beauty,

rapture, and labour. “I know of no other

Christianity, and of no other

gospel, than the liberty both of body and mind to

exercise the divine arts

of imagination, the real and eternal world of which

this vegetable universe is

but a faint shadow, and in which we shall live in

our eternal or imaginative

bodies when these vegetable mortal bodies are no

more. The Apostles knew

of no other gospel. What are all their spiritual gifts

? What is the divine

spirit ? Is the Holy Ghost any other than an intellectual

fountain ? What is

the harvest of the gospel and its labours ? What is the

talent which it is a curse

to hide ? What are the treasures of heaven which we

are to lay up for our-

selves ? Are they any other than mental studies and

performances ? What

are all the gifts of the gospel, are they not all mental

gifts ? Is God a spirit

who must be worshipped in spirit and truth ? And are

not the gifts of the

spirit everything to man ? O ye religious ! discountenance

every one among

you who shall pretend to despise art and science. I call upon

you in the

name of Jesus ! What is the life of man but art and science ? Is it

meat

and drink ? Is not the body more than raiment ? What is mortality but the

things relating to the body which dies ? What is immortality but the things

34 THE SAVOY

relating to the spirit which lives eternally ? What is the joy of Heaven but

improvement in the things of the spirit ? What are the pains of Hell but

ignorance, idleness, bodily lust, and the devastation of the things of the

spirit ? Answer this for yourselves, and expel from among you those who

pretend

to despise the labours of art and science, which alone are the labours

of the

gospel. Is not this plain and manifest to the thought ? Can you think

at all,

and not pronounce heartily that to labour in knowledge is to build

Jerusalem,

and to despise knowledge is to despise Jerusalem and her builders ?

And

remember, he who despises and mocks a mental gift in another, calling it

pride,

and selfishness, and sin, mocks Jesus, the giver of every mental gift,

which

always appear to the ignorance-loving hypocrites as sins. But that

which is sin

in the sight of cruel man is not sin in the sight of our kind God.

Let every

Christian as much as in him lies engage himself openly and publicly

before all

the world in some mental pursuit for the building of Jerusalem.” I

have given

the whole of this long passage, because, though the very keystone

of his

thought, it is little known, being sunk, like nearly all of his most

profound

thoughts, in the mysterious prophetic books. Obscure about much

else, they are

always lucid on this one point, and return to it again and

again. “I care not

whether a man is good or bad,” are the words they put

into the mouth of God,

“all that I care is whether he is a wise man or a fool.

Go put off holiness and

put on intellect.” This cultivated life, which seems to us

so artificial a

thing, is really, according to them, the laborious re-discovery of

the golden

age, of the primeval simplicity, of the simple world in which Christ

taught and

lived, and its lawlessness is the lawlessness of Him “who being

all virtue

acted from impulse, and not from rules,”

And his seventy disciples sent

Against religion and government.

The historical Christ was indeed no more than the supreme symbol

of the

artistic imagination, in which, with every passion wrought to

perfect beauty by

art and poetry, we shall live, when the body has passed away

for the last time ;

but before that hour man must labour through many lives and

many deaths.

“Men are admitted into heaven, not because they have curbed and

governed their

passions, but because they have cultivated their understandings.

The treasures

of heaven are not negations of passion, but realities of

intellect, from which the

passions emanate, uncurbed in their eternal glory.

The fool shall not enter

into heaven, let him be ever so holy. Holiness is not

the price of entering

into heaven. Those who are cast out are all those who,

having no passions of

BLAKE’S ILLUSTRATIONS TO THE DIVINE COMEDY 37

their own, because no intellect, have spent their lives in curbing and governing

other people’s by the various arts of poverty and cruelty of all kinds. The

modern Church crucifies Christ with the head downwards. Woe, woe, woe to

you hypocrites.” After a time man has “to return to the dark valley whence

he

came and begin his labours anew,” but before that return he dwells in the free-

dom of imagination, in the peace of “the divine image,” “the divine vision,” in

the peace that passes understanding, and is the peace of art. “I have been very

near the gates of death,” Blake wrote in his last letter, “and have returned very

weak and an old man, feeble and tottering, but not in spirit and life, not in

the

real man, the imagination, which liveth for ever. In that I grow stronger

and

stronger as this foolish body decays . . . Flaxman is gone and we must all

soon

follow, everyone to his eternal home, leaving the delusions of goddess

Nature

and her laws, to get into freedom from all the laws of the numbers,” the

multi-

plicity of nature, “into the mind in which everyone is king and priest

in his own

house.” The phrase about the king and priest is a memory of the

crown and

mitre set upon Dante’s head before he entered Paradise. Our

imaginations are

but fragments of the universal imagination, portions of the

universal body of

God, and as we enlarge our imagination by imaginative

sympathy, and transform,

with the beauty and the peace of art, the sorrows and

joys of the world, we put

off the limited mortal man more and more, and put on

the unlimited “immortal

man.” “As the seed waits eagerly watching for its

flower and fruit, anxious its

little soul looks out into the clear expanse to

see if hungry winds are abroad with

their invisible array ; so man looks out in

tree, and herb, and fish, and bird,

and beast, collecting up the fragments of

his immortal body into the elemental

forms of everything that grows. … In

pain he sighs, in pain he labours in

his universe, sorrowing in birds over the

deep, or howling in the wolf over the

slain, and moaning in the cattle, and in

the winds.” Mere sympathy for all

living things is not enough, because we must

learn to separate their “infected”

from their eternal, their satanic from their

divine part ; and this can only be

done by desiring always beauty ; the one

mask through which can be seen the

unveiled eyes of eternity. We must then be

artists in all things, and under-

stand that love and old age and death are

first among the arts. In this sense,

he insists that “Christ’s apostles were

artists,” that “Christianity is Art,” and

that “the whole business of man is

the arts.” Dante, who deified law, selected

its antagonist, passion, as the

most important of sins, and made the regions where

it was punished the largest.

Blake, who deified imaginative freedom, held

“corporeal reason” for the most

accursed of things, because it makes the

imagination revolt from the

sovereignty of beautyand pass under the sovereignty

38 THE SAVOY

of corporeal law, and this is “the captivity in Egypt.” True art is expressive

and symbolic, and makes every form, every sound, every colour, every gesture,

a

signature of some unanalyzable, imaginative essence. False art is not expres-

sive but mimetic, not from experience, but from observation ; and is the

mother

of all evil, persuading us to save our bodies alive at no matter what

cost of

rapine and fraud. True art is the flame of the last day, which begins

for every

man, when he is first moved by beauty, and which seeks to burn

all things until

they “become infinite and holy.”

Blake’s distaste for Dante’s philosophy did not make him a less

sympathetic illustrator, any more than did his distaste for the

philosophy

of Milton mar the beauty of his illustrations to “Paradise Lost.” The

illus-

trations which accompany the present article are, I think, among the

finest

he ever did, and are certainly faithful to the text of “The Divine

Comedy.”

That of Dante talking with Uberti, and that of Dante in the circle of

the

thieves, are notable for the flames which, as always in Blake, live with a

more vehement life than any mere mortal thing : fire was to him no unruly

offspring of human hearths, but the Kabalistic element, one fourth of creation,

flowing and leaping from world to world, from hell to hell, from heaven to

heaven ; no accidental existence, but the only fit signature, because the only

pure substance, for the consuming breath of God. In the man, about to

become a

serpent, and in the serpent, about to become a man, in the second

design, he

has created, I think, very curious and accurate symbols of an

evil that is not

violent, but is subtle, finished, plausible. The sea and

clouded sun in the

drawing of Dante and Virgil climbing among the rough

rocks at the foot of the

Purgatorial mountain, and the night sea and spare

vegetation in the drawing of

the sleep of Virgil, Dante and Statius near to

its summit, are symbols of

divine acceptance, and foreshadow the land-

scapes of his disciples Calvert,

Palmer, and Linnell, famous interpreters of

peace.

The faint unfinished figures in the globe of light in the drawing

of

the sleepers are the Leah and Rachel of Dante’s dream, the active

and

the contemplative life of the spirit, the one gathering flowers, the

other

gazing at her face in the glass. It is curious that Blake has made no

attempt, in these drawings, to make Dante resemble any of his portraits,

especially as he had, years before, painted Dante in a series of por-

traits of

poets, of which many certainly tried to be accurate portraits. I

have not yet

seen this picture, but if it has Dante’s face, it will convince

me that he

intended to draw, in the present case, the soul rather than the

BLAKE’S ILLUSTRATIONS TO THE DIVINE COMEDY 41

body of Dante, and read “The Divine Comedy” as a vision seen not in the

body

but out of the body. Both the figures of Dante and Virgil have the

slightly

feminine look which he gave to representations of the soul.

W. B. YEATS.

“VENITE, DESCANDAMUS”

LET be at last : give over words and sighing,

Vainly were all things said :

Better, at last, to find a place for lying,

Only dead.

Silence were best, with songs and sighing over ;

Now be the music mute :

Now let the dead, red leaves of autumn cover

A vain lute !

Silence is best : for ever and for ever,

We will go down to sleep,

Somewhere, beyond her ken, where she need never

Come to weep.

Let be at last : colder she grows, and colder ;

Sleep and the night were best ;

Lying, at last, where we cannot behold her,

We may rest.

TWO FOOLISH HEARTS

SUMMER had passed, the harvest was ingathered, and the days began to close in.

At the Hill Farm was heard the euphonious boom of

the threshing machine. It was music to many in the

neighbourhood, but to none more than to the little boy

Reggie.

He had become a fixture, so to speak, at the Farm. Since the day when

he crept through the hole in the orchard hedge, he had grown to be one of the

family. Everybody liked the boy: two on the farm—Letty and Clem—

had come to love him.

There is so much to love in a child—his smile, his general prettiness, his

bright and often saucy tongue, his way of looking at things, his mode of doing

them, and his highly ingenious plan of obtaining his desires. These are some

of the arts and charms of child life, and they win, yes, they win—often against

the adult’s better judgment.

Letty had grown to love the boy as her own. If he had not made

his appearance on the Farm just after breakfast, she would go out first into the

Croft and then into the Pond Close and call “Reg—gie, Reg—gie,” in the

same cooing sort of way as she used to call Clem in his childhood; and if the

little fellow was within earshot, he would gallop to her and spring into her

open arms with a warbling laugh which did the heart good to hear.

He was the revived sweets of old days to Letty; a new bit of colouring

on her picture. He was more than this to her sometimes—he was Luce in

knickerbockers.

She did not like that fancy so well, though her feeling against Luce was

softening through contact with her child. She had not seen Luce, however.

Though Reggie had been a daily visitor to the farm since the end of June, and

it was now the end of September, the red-haired flame of Clem had not once

put in an appearance.

46 THE SAVOY

Her Rubens-like beauty had blushed unseen by Letty. She bestowed it

chiefly upon her mother in their little cottage in Radbrooke Bottom; it

was only at times—in the silent and long summer nights when few people

were visible—that she went more than a stone’s threw from her home.

The shorter days drew her out more. It was natural that it should

be so, though eminently displeasing that so fair a flower should perforce

have to exist under a cloud. This angered Clem. Luce at Radbrooke,

indoors, and away from him and the farm, was no better than Luce at

Brookington.

Many girls, similarly situated to Luce, would have “brazened it out”

Luce might, perhaps, have felt less the necessity of hiding herself away from

everybody, had she not heard the opinion entertained of her by Letty Martin.

She had heard that—and it was sufficient for her to almost nail herself to the

table leg in her mother’s kitchen.

But now that the days began to be chary of their light towards six o’clock

in the evening, Luce began to be a little more prodigal of her presence. Three

years ago, or rather more, she used to court the sunlight; now she haunted the

shades. To a really pure girl the knowledge of having committed an offence

against society, if not against Nature, is all that is needed to bring the blush to

the cheek at every awkward or trivial meeting. Luce, though a mother, had

by no means lost her purity. In the evening dusk she could blush without

detection.

So she sauntered down the garden path on this warm and calm evening

at the end of September; on the evening of the annual village wake.

“You baint goin’ to the wake, be ye, Luce, lass?” said her mother as

she stepped out.

“I should like to go, mother, for sake of the dancin’; but I donna think

I will.”

“If I was thee, my gel, I should’na. Theer’ll be all the village theer,

besides Brookington folk; an’ summat ‘ull be sure to be said ’bout thee. An’

as for dancin’, Luce—well, you might nor be short o’ partners, my gel; but

I

should’na—no, I should’na.”

“I’ll walk i’ the lane a bit, mother,” replied Luce, slowly. “If Reg cries,

I’ll come in.”

“Donna thee fret about little waxwork, deary; I’ll see to ‘im.”

When Luce was out of hearing, Mrs. Cowland wiped a tear out of the

corner of her eye, and sighed to herself: “The beautifulest peaches be the

fust to goo spect. Poor Luce, beautiful Luce! To think as I should hev ‘ad

TWO FOOLISH HEARTS 47

such a beauty, the envy of all the mothers i’ Radbrooke, an’ then for she

to hev come to this. It breaks me heart when I think on’t.”

True, honest, motherly instinct is not so common that one can afford to

smile at the simple sentiments of Mrs. Cowland. They are rare in humble

spheres, far rarer in higher circles. The lowliest flowers are the tenderest, the

sweetest, the truest, the purest.

Meanwhile, with a full heart, and a set of confusing thoughts, which

seemed born only to be killed, Luce sauntered along the lane.

There were no dwellings eastward beyond Luce’s cottage. There was a

pond, called “The Green Pond” by the children, on account of its entire

surface being covered with a thin green film, on the north side, dangerously

near the footpath, and left open for any luckless child to fall into; there was

also a curve in the lane northward; but no more domiciles.

Beyond Luce’s cottage the lane was a pure lane: hedges each side, com-

posed of hawthorn, blackthorn, buckthorn, blackberry, bramble, and elder;

with, at intervals, a tall elm, ash, or oak, whose spreading branches almost

shut out the sky from above, and made the lane shady even in the strongest

light.

It was a pure lane—a leafy lover’s lane.

To-night it wore an intensely delightful aspect. It was moonlit. Few

trees grew at the west end, and when the moon reached a certain altitude it

shot a ray of effulgence down that avenue-like Warwickshire lane like a light

in a railway tunnel. Luce looked like an animated poppy walking through

the light into darkness, for the moonrays did not penetrate to the lane’s end.

Luce had no intention of going to the wake. There were reasons why

she should not. Yet she had implanted in her the natural rustic longing to

attend the annual festivity on the green waste near the church.

The wake was a great occasion at Radbrooke: a loved occasion, a merry

occasion, and an occasion looked forward to for weeks beforehand. It was the

one time of the year when all the villagers and the occupants of the surround-

ing farms met together for a day’s junketting and pleasantry. There were

shows, merry-go-rounds, shooting galleries, cocoa-nut throwing, and, to crown

all, dancing on the green to the often discordant music of the Brookington

band.

These pleasures are rustic, Bohemian if you will; but they are the natural

pleasures of Strephon and Phyllis, and they attract—yes, they attract. They

are the sole amusements of the peasant, isolated in his own greenwood; and

though the gaily-painted caravan and roundabout are incongruous ex-

48 THE SAVOY

crescences upon the landscape, their coming is an exciting event in the life of

the villager.

The roadway or street of the village ran parallel with Radbrooke Bottom,

and at its eastward end it sloped southward so decidedly that the lane and the

street at that end were not more than twenty yards apart. As Luce stood at

the junction the sounds of the blaring music of the roundabouts floated to her

ear, mingled with the peals of laughter and the shouts of merry-makers.

She was but a young thing, full of life, and with a taste for enjoyment.

She did not intend to take part in the wake, but the alluring sounds of the

pleasures provided there drew her feet round the bend of the road to a point

where it joined the village street, and commanded a fine view of the motley

fair.

What a sight it was, just on the outskirts of silence!

To the contemplative being who stood where Luce was standing, the

contrast between the two scenes would have seemed extraordinary, not to say

terrible. Two distinct worlds, they were separated from each other only by a

few yards. Luce was standing in a silent world, which gave forth no sound;

the world before her blazed with light, colour, and movement, and dinned the

ears with its noise.

And above the flaming oil-lamps, the madly-circling roundabouts, the

wildly dancing people, who seemed never to tire through dance after dance,

above the shouts of the showmen, the scream of the steam-whistle, the laugh

of the light-hearted, looking down on a scene so foreign to the landscape in

which it was set, was the square, lichen-grown tower of the parish church of

Radbrooke; looking down with a calm, dignified, and venerable air through

its eye-like window upon this saturnalia of village life.

Luce was transfixed at her point of vantage. She never moved an inch

more forward, but stood there gazing wistfully at the scene, and especially at

the dancers, like one who would have liked to mingle with them, but was too

shy to enter. If anyone on the edge of the fair and in its full blaze of light,

had looked towards the bend in the road which led downward to Radbrooke

Bottom, they would have beheld a lovely young face framed in a garland of

red hair, looking out through the darkness—Luce’s Rubens-like face.

“Thy partner inna theer, Luce,” said a voice in the shadow behind

her.

Luce turned quickly round, for she was rather startled, and saw beside her

the fine face and large form of Moll Rivers. She, like Luce, was without her

hat, and when she came forward and stood on a level with Luce, so that the

TWO FOOLISH HEARTS 49

light from the fair flashed full upon their faces, the contrast in their appearance

was very striking.

Moll with her superb height and mass of raven black hair might have

passed for the Queen of Night; she was in her element, her latitude, her clime

—lusty-limbed and strong. Luce, with her smaller stature and red hair could

pass for Aurora, the Queen of the Morning. She had the appearance of being

out of her element, her latitude, her clime; she was dainty-limbed and younger

in years than Moll.

Both looked at each other curiously and in some confusion. Moll had a

melancholy look and a rather untidy air; the hooks of her bodice were

undone, showing a portion of her rounded breasts panting beneath. A cloud

of inexpressible weariness sat in her eyes and upon her forehead. She looked

tired of living.

“Thy partner inna theer, Luce,” she repeated, inclining her head towards

the dancers.

“My partner, Molly?” replied Luce, in some surprise.

“Yes, I’ve bin all round the wake, in an’ out the footers, round the dobby

horses, an’ by the shooting galleries, an’ canna find ‘im. Let ‘s go away.”

They turned down the lane into the shadow. Then Luce spoke.

“It seems from what you say, Moll, that you’ve been lookin’ for a partner.

I hanna got no partner, an’ hanna been seeking for one.”

“Maybe you might soon hev ‘ad one, Luce?” returned Moll with a mean-

ing look.

“May be,” said Luce, with some attempt at dignity.

“That is if you hanna left youm behind at Brookington.”

It was one of those deadly thrusts often dealt out by uncultured natures.

If it had been daylight the beholder would have seen the colour rush headlong

into Luce’s face and spread all down her neck; as it was moonlight, the effect

of Moll’s words was not observed in her face, though her voice shook when she

next spoke.

“My business is my business, Moll, if so be it’s at Radbrooke or Brooking-

ton. I donna think you ought to trouble yourself about it.”

“Perhaps not,” said Moll. “I’ve no call to say anything, I hevn’t.

I must see all an’ say nothing. I mun bear all an’ do nothin’.”

“I donna know what you mean.”

“No, nobody knows what I mean. ‘Tis as the parson said in his sarment

on Sunday—yes, Miss Luce, I did go to church on Sunday, an’ you’ve no call

to look so dubersome, for some folks inna so black as they’re painted; he said

50 THE SAVOY

in his sarment as none be so blind as them as wunna see, an’ that’s it. You

know what I mean, you can see what I mean, yet you make believe ye donna

know.”

Luce did not reply. She was burning and trembling at the same time.

She sauntered quietly on, with the commanding figure of Moll at her

side like her elongated shadow. Every now and then they walked out of the

darkness into a thin line of moonlight which came through a gap in the trees;

then it was seen that both their faces were flushed, and that Moll’s in particular

had a cloud of anger growing over it.

“You donna speak, Luce?” she went on. “Perhaps you be ashamed to.

You were such a good little gell once, an’—I wish I may die if I’m tellin’ a lie

—I was very fond on thee. But you’ve turned out a faggot, Luce; yes, a very

faggot.”

“And pray, what hev I done to thee, Moll, to be called a faggot by thee?”

Luce was nearly breaking down; the vehemence of Moll she had not bar-

gained for. Poor girl, she was receiving punishment for her sin all round—

from her own sex. It was first her mother, then Letty Martin, and now Moll.

Why was it, she inwardly inquired, that women are so cruel to women? She

expected pity and obtained punishment.

A ray of moonlight fell upon her while Moll was in shadow. It glorified

her. It even lit up the glistening tears in the corners of her eyes and made

them shine like diamonds. Moll looked out of the darkness at her with great

admiration.

“Thou art a pretty faggot, Luce, a very pretty faggot; but thou’rt a

faggot all the same. I canna wonder at men bein’ fond on thee. Giv’ me

thy hair, Luce, thy bonnie red hair as he be so in love with, an’ I’ll never call

thee a faggot no more.”

She caught hold of Luce’s hair, and held it by her own, comparing the

colours.

“Mine’s longer and thicker nor yourn, beautiful hair, inna it? But not

showy like yourn. Men like showy things. Then you’ve got blue eyes, Luce,

an’ mine be dull an’ dark. You’re altogether more pretty to look at nor I am.

Men like pretty things, little toy things like you, an’ I’m big an’ bold, an dowdy

—no wonder he doesna like me.”

She paused a moment, looking steadfastly at Luce.

“But he might hev come to like me, if you had’na turned up here agen

like the bad penny that you are. Yes,” she added almost fiercely, and with

uncontrollable bitterness, “you are a faggot, Luce, else you’d hev stopped at

TWO FOOLISH HEARTS 51

Brookington with your misgotten brat, an’ not come here agen with your

winnin 1 ways, pretty face, an’ carrotty hair, to ‘ang yourself on Clem agen.”

Luce’s spirit was bent but not broken. She looked at Moll with an

awakening glance and with a flushed and defiant air.

“Oh! I see what you mean now, Molly. You want Clem, an’ because I’ve

come back you think you shanna get him. Well, my home ‘s at Radbrooke. I

came home, not to try and win Clem away from you or anyone else, but to

try and live in peace.”

“You’ve bewitched ‘im—you, another man’s light-o’-love.”

That epithet again! It stabbed Luce to the heart like a knife.

She had done wrong, she had sinned, she had prayed for forgiveness.

Was her punishment never to be completed? Why should she be condemned

to be brow-beaten by this girl? Had she not suffered enough in her own

heart for her folly, but that she must be let down before every villager and

made to ask pardon from them all?

Here was this girl, this Moll Rivers, who was known by all the village to