XML PDF

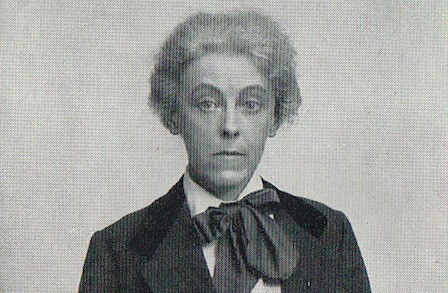

Charlotte Mew

(1869 – 1928)

Charlotte Mary Mew was born on London’s Doughty Street in November 1869. Her father, Frederick Mew (1832–1898), son of farmers, moved to London to become an architect under the training of H. E. Kendall (1805-1885), and married Kendall’s daughter Anne (1837–1923). Mew was the third of seven children, of which three died in childhood, and two were institutionalized in a mental hospital. Mew and her sister Anne (1873–1927), the only long-surviving siblings, remained close until Anne’s death. Although she was known as an enthusiastic figure amongst her social circle, Mew was haunted by her family’s history of mental illness and death, which would become evident in some of her writings. Following her sister Anne’s death in 1927, Mew’s mental health deteriorated, and she was admitted into a nursing home in February 1928, where she committed suicide within a month.

Most of Mew’s life was spent in the intellectually rich Bloomsbury district in London, which granted her access to cultural circles that would become valuable for her literary career. She attended Lucy Harrison’s School for Girls on Gower Street, and became a boarder at the headmistress’ house. The works of Harrison’s favourite authors, which included Robert (1812–1889) and Elizabeth Barrett Browning (1806–1861), Dante Gabriel (1828–1882) and Christina Rossetti (1830–1894), would become an influence on Mew’s own writings (Fitzgerald, Charlotte Mew and her Friends, 31–2). Indeed, poems such as “The Farmer’s Bride” and “Madeleine in Church,” included in The Farmer’s Bride (1916)—the only poetry collection published during Mew’s lifetime—are composed as dramatic monologues, a form popularised by Robert Browning. The theme of the fallen woman, explored in works such as Elizabeth Barrett Browning’s Aurora Leigh and Dante Gabriel Rossetti’s “Jenny,” can be found in Mew’s “She was a sinner” and “At the Convent Gate,” both included in her posthumous second collection, The Rambling Sailor (1929). Additionally, some of Mew’s poems resemble Christina Rossetti’s in tone and subject-matter. For instance, “Saturday Market,” also included in her collection of 1929, is reminiscent of “Goblin Market,” as both explore the dynamics formed within a market, particularly as it pertains to temptation, with a female subject as the protagonist. Similarly to Christina Rossetti’s “Remember me when I am gone away,” the speaker in Mew’s “A Farewell,” published posthumously later on in the twentieth century, faces and embraces death as an inevitable, yet not necessarily tragic fate, as the lyrical subjects of both poems remind others to “smile” as they remember them. Due to Mew’s adoption and adaptation of Christina’s wintriness, especially concerning love, as well as the thematic presence of loss, death, and womanhood in her works, Mew can be read as a successor to Christina Rossetti’s poetic legacy.

After moving from Doughty Street to Gordon Square in 1888, close to University College London, Mew began to attend talks and lectures at the university. She also visited art galleries, and attended Henry Harland’s evening gatherings, also frequented by prominent fin-de-siècle figures such as Arthur Symons, George Moore, Henry James, and Kenneth Grahame. Though reserved regarding her private life, Mew was not secluded from the literary social circle of her time. Jessica Walsh highlights this relation between privacy and popularity by explaining that whilst Mew adopted mannerisms that aligned her with the contemporary New Woman (“swearing, smoking, and rather mannish dress”), she was not outspoken regarding her views on politics and social causes, such as women’s suffrage. Walsh adds that her discreet homosexuality could have prevented her from being vocal about certain issues, as Mew “could not suppress her feeling of difference long enough to become part of any community or group” (222).

Notwithstanding her repression of her sexual preferences, Mew’s queerness manifested itself through her literary engagements. Mew fell in love with Ella D’Arcy, who, despite not returning Mew’s passion, became a close friend and admirer of her works. D’Arcy’s role in The Yellow Book ’s editorial board brought Mew closer to the literary circle to which she would soon belong. Mew also developed feelings for the writer May Sinclair (1863-1946), who read Mew’s poetry and offered advice. It was also Sinclair who introduced Mew’s poetry to Ezra Pound (1885–1972), who became an admirer of her work, thereby further expanding Mew’s literary network.

Also illustrative of Mew’s guarded queerness is her contribution to The Yellow Book, specifically the short story “ Passed,” published in the magazine’s second number of July 1894. The story narrates a woman’s experience wandering in the streets of London one night, until she encounters a girl. The physical attraction between the two is then thoroughly described, as both women are magnetically and inexplicably drawn to each other. The girl guides the narrator to her house, where the girl’s sister dies. Months later, the protagonist encounters the same girl walking in the streets of the city, this time accompanied by a man. The girl, however, does not seem to recognise the narrator. It was with “Passed” that Mew made her public debut, as this was her first literary work to be published. Most of Mew’s following publications were stories and essays in magazines such as Pall Mall (1893-1914), Temple Bar (1860-1906), and The Englishwoman (1909-1921). These included the stories “Some Ways of Love” ( Pall Mall Magazine, September 1901) and “An Open Door” ( Temple Bar, January 1903), and the essays “The Poems of Emily Brontë” ( Temple Bar, August 1904) and “Mary Stuart in Fiction” ( The Englishwoman, April 1912). Although a few of her poems, such as “The Fête,” had been individually published in periodicals (see list of selected publications below), her first collection of poems only appeared in 1916 with The Farmer’s Bride , re-published in 1921 in the United States with an additional eleven poems. Despite the admiration of Mew’s fellow writers and their efforts to promote her work, her poetry was not as successful as her prose publications. A year following her death, a new collection of poems titled The Rambling Sailor was published with a memoir by Alida Monro (1892–1969), wife of the poet Harold Monro (1879–1932), and one of the first figures to promote Mew’s work after her death. Mew’s complete collected works would not be published, however, until the last decades of the twentieth century.

Nevertheless, it is Mew’s poetry, rather than her prose, that continues to fascinate and intrigue scholars today. Whilst her poetry starts from elements drawn from Romantic and early to mid- Victorian poetry, these are distinctively combined with Decadent and Modernist features. Her interest in being part of The Yellow Book, for instance, specifically with a story that conveys the cosmopolitanism and queer sexual undertones that reflect not only the progressiveness of the magazine, but also the sexual transgression of the fin-de-siècle cultural milieu, emphasises her links to Decadence. Her experimentation with poetic forms, particularly free verse, and the alienation manifest in poems such as “The Forest Road,” first published in The Farmer’s Bride edition of 1916, on the other hand, allude to Modernism. As a result, Angela Leighton includes Mew in her discussion of the affective tradition of Victorian Women Poets: Against the Heart (1992), whereas Elaine Showalter considers her a “daughter of Decadence” (xvii), and Elizabeth Black places her alongside T. S. Eliot (1888-1965) in The Nature of Modernism (2017).

It is not only regarding literary movements that her works are challenging to position. Her poetry conveys a constant uncertainty, whether that is through the exploration of life and death, passion and loss, or the inclusion of problematic autobiographical details. For instance, Nunhead Cemetery in south London, where Mew’s brother Henry (1865-1901) was buried, becomes the subject and title of a poem. Mew’s complicated relationship with sexuality would also transpire in poems such as “She was a sinner,” only published after the author’s death, and earlier poems such as “Madeleine in Church,” already included in The Farmer’s Bride in 1916, where pursuing the body’s desires leads to sorrow and devastation. A pact that Mew made with her sister helps to illustrate the extent of her concerns. The sisters swore to “never marry for fear of passing on the mental taint that was in their heredity” (Monro xiii). Whilst this reluctance towards marriage can be partially understood through Mew’s homosexuality, refusing to marry would also eliminate the possibility of motherhood, and of continuing what Mew considered to be the cursed legacy of her family’s mental illness.

At her wish, Mew was buried in the same grave as her sister Anne in Hampstead Cemetery. As the inscription for their tombstone, Mew chose a verse from Dante’s Purgatorio, “Cast down the seed of weeping, and attend” (Canto 31), alluding to Beatrice’s confrontation with Dante for having yielded to the sirens’ temptation. Given Mew’s suppressed desire, this inscription can be read as her self-inflicted, eternal punishment for sins not committed, but by which she was tempted. On the other hand, considering that this passage inscribes her joint grave with Anne, who shared Mew’s aversion to bodily reproduction, it may allude to their mutual commitment to purity as a way of avoiding perpetuating their family’s history. The inscription sustains Mew’s mysterious character.

Though scholars and readers are increasingly invested in decoding Mew’s writings, it is their enigmatic nature that makes them historically, literarily, and poetically unique. Although the general public may have overlooked her poetic abilities during her lifetime, she did not go unnoticed by her contemporary cultural figures. While Virginia Woolf considered her “unlike anyone else” (Fitzgerald, Charlotte Mew and her Friends, 1), Mew’s friend and admirer Thomas Hardy, whose Sue in Jude the Obscure has been considered to be based on Mew’s life and character (Davidow 441), commented in her lifetime that “she is far and away the best living woman poet, who will be read when others are forgotten” (Fitzgerald, Charlotte Mew and her Friends, 1).

© 2021, Catia Rodrigues, PhD Candidate, Royal Holloway, University of London, UK

Catia Rodrigues is a PhD candidate at Royal Holloway, University of London, funded by the AHRC/TECHNE DTP. Her research is on the networks formed by women associated with the Pre-Raphaelite movement as artists, poets, patrons, models, art-critics, exploring their collective artistic identity, and their impact on the artistic direction of the Pre-Raphaelite label.

Selected Publications by Charlotte Mew

- “A Fatal Fidelity.” Cornhill Magazine, vol. 167, Autumn 1953, pp. 67-80.

- “A Reminiscence of Princess Mathilde Bonaparte.” Temple Bar , vol. 129, May 1904, pp. 541-48.

- “A White Night.” Temple Bar, vol. 127, May 1903, pp. 625-39.

- “An Old Servant.” New Statesman, vol. 2, October 1913, pp. 49-51.

- “An Open Door.” Temple Bar, vol. 127, January 1903, pp. 71-91.

- Charlotte Mew: Collected Poems & Prose, edited by Val Warner. Virago Press, 1982.

- Collected Poems of Charlotte Mew, edited by Alida Monro. Macmillan, 1953.

- “In the Curé’s Garden.” Temple Bar, vol. 125, June 1902, pp. 667-80.

- “Mademoiselle.” Temple Bar, vol. 129, January 1904, pp. 90-101.

- “Mark Stafford’s Wife.” Temple Bar, vol. 131, January 1905, pp. 67-94.

- “Mary Stuart in Fiction.” The Englishwoman, vol. 14, April 1912, pp. 59-73.

- “Men and Trees I.” The Englishwoman, vol. 17, February 1913, pp. 181-88.

- “Men and Trees II.” The Englishwoman, vol. 17, March 1913, pp. 311-19.

- “Miss Bolt.” Temple Bar, vol. 122, April 1901, pp. 484-93.

- “Notes in a Britany Convent.” Temple Bar, vol. 124, October 1901, pp. 238-47.

- “Passed.” The Yellow Book, vol. 2, July 1894, pp. 121-41. The Yellow Book Digital Edition, edited by Dennis Denisoff and Lorraine Janzen Kooistra, 2010-2014. Yellow Nineties 2.0, Ryerson University Centre for Digital Humanities, 2019. https://1890s.ca/YBV2_mew_passed/

- “Péri en mer (Cameret).” The Englishwoman, vol. 20, November 1913, p. 136.

- Saturday Market. Macmillan, 1921.

- “Some Ways of Love.” Pall Mall Magazine, vol. 24, September 1901, pp. 301-10.

- “The China Bowl.” Temple Bar, vol. 118, September 1899, pp. 64-90.

- “The Country Sunday.” Temple Bar, vol. 132, November 1905, pp. 598-600.

- The Farmer’s Bride. Poetry Bookshop, 1916.

- “The Governess in Fiction.” The Academy, vol. 57, August 1899, pp. 163-4.

- “The Hay-Market.” New Statesman, vol. 2, February 1914, pp. 595-97.

- “The London Sunday.” Temple Bar, vol. 132, December 1905, pp. 703-7.

- “The Poems of Emily Brontë.” Temple Bar, vol. 130, August 1904, pp. 153-67.

- The Rambling Sailor. Poetry Bookshop, 1929.

- “The Smile.” Theosophist, vol. 35, May 1914, pp. 274-82.

- “The Wheat.” Time and Tide, 20 February 1954, pp. 237-8.

- “To a Little Child in Death.” Temple Bar, vol. 124, September 1901, p. 55.

- “V.R.I.” Temple Bar, vol. 122, March 1901, p. 290.

Selected Publications about Charlotte Mew

- Black, Elizabeth. “‘Bury Your Heart’: Charlotte Mew and the Limits of Empathy.” Humanities, vol. 8, no. 4, 2019, p. 1-10., doi:10.3390/h8040175.

- —. The nature of modernism: ecocritical approaches to the poetry of Edward Thomas, T.S. Eliot, Edith Sitwell and Charlotte Mew . Routledge, 2017.

- Bristow, Joseph. “Charlotte Mew’s Aftereffects.” Modernism/modernity, vol. 16, no. 2, 2009, pp. 255-280, doi:10.1353/mod.0.0084.

- Copus, Julia. This Rare Spirit: A Life of Charlotte Mew . Faber, 2021.

- Davidow, Mary C. “Charlotte Mew and the Shadow of Thomas Hardy.” Bulletin of Research in the Humanities, vol. 81, 1978, pp. 437-447.

- Denisoff, Dennis. “Grave Passions: Enclosure and Exposure in Charlotte Mew’s Graveyard Poetry.” Victorian Poetry, vol. 38, no. 1, 2000, pp. 125-140, https://jstor.org/stable/40004296.

- Fitzgerald, Penelope. Charlotte Mew and her Friends. Collins, 1984.

- —. “Mew, Charlotte Mary (1869–1928), poet.” Oxford Dictionary of National Biography , 2008. Oxford University Press, https://www.oxforddnb.com/view/10.1093/ref:odnb/9780198614128.001.0001/odnb-9780198614128-e-35005.

- Forlini, Stefania. “The Machinic-Human Body and Charlotte Mew’s Aesthetic of (Dis)Embodiment.” Gothic Studies, vol. 5, no. 1, 2003, pp. 111–120., doi:10.7227/gs.5.1.7.

- Fry, Emma-Jane. Marks upon the snow: Transgression in the work of Charlotte Mew . King’s College London University of London, 2007. PhD dissertation. EThOS, https://ethos.bl.uk/OrderDetails.do?uin=uk.bl.ethos.520294

- Griffiths, Joanna Megan. ‘A sort of suicide’: Charlotte Mew (1869-1928) and literary fashion . University of Oxford, 1998. PhD dissertation. EThOS, https://ethos.bl.uk/OrderDetails.do?uin=uk.bl.ethos.326630.

- Gutin, Stanley Samuel. The poems of Charlotte Mew: a critical study . University of Maryland Press, 1956.

- Henderson, K. K. “Mobility and Modern Consciousness in George Egerton’s and Charlotte Mew’s Yellow Book Stories.” English Literature in Transition, 1880-1920, vol. 54, no. 2, 2011, pp. 185-211, doi: 10.1353/elt.2011.0021.

- Howarth, Peter. “Fateful Forms: A. E. Housman, Charlotte Mew, Thomas Hardy and Edward Thomas.” The Cambridge Companion to Twentieth-Century English Poetry , edited by Neil Corcoran, Cambridge University Press, 2007, pp. 59–73, doi: 10.1017/CCOL052187081X.005.

- Hussain, Sarah. “Said to be a writer”: tradition, gender and identity in the poetry of Charlotte Mew . University of London, 2002. PhD Dissertation. Queen Mary, University of London, https://qmro.qmul.ac.uk/xmlui/handle/123456789/1506.

- Leighton, Angela, Victorian Women Poets: Against the Heart. Harvester Wheatsheaf, 1992.

- Merrin, Jeredith. “The Ballad of Charlotte Mew.” Modern Philology, vol. 95, no. 2, 1997, pp. 200-217, https://www.jstor.org/stable/438989.

- Mizejewski, Linda. “Charlotte Mew and the Unrepentant Magdalene: A Myth in Transition.” Texas Studies in Literature and Language, vol. 26, no. 3, 1984, pp. 282-302, https://www.jstor.org/stable/40754759.

- Monro, Alida. Introduction. Collected Poems of Charlotte Mew, by Charlotte Mew, edited by Alida Monro, Macmillan, 1953.

- Newton, John. “Charlotte Mew’s Place in the Future of English Poetry.” New England Review , vol. 18, no. 2, 1997, pp. 32-46, https://www.jstor.org/stable/40243179.

- Raitt, Suzanne. “Charlotte Mew and May Sinclair: A love-song.” Critical Quarterly , vol. 37, no. 3, 1995, pp. 3-17, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8705.1995.tb01066.x.

- Rice, Nelljean McConeghey. A New Matrix for Modernism: A Study of the Lives and Poetry of Charlotte Mew and Anna Wickham . Routledge, 2003.

- Robertson, David A. “Contemporary English Poets: Charlotte Mew.” The English Journal , vol. 15, no. 5, 1926, pp. 344-347, http://www.jstor.org/stable/802165.

- Schenck, Celeste M. “Charlotte Mew.” The Gender of Modernism: A Critical Anthology , edited by Bonnie Kime Scott, Indiana University Press, 1990, pp. 316–322.

- Showalter, Elaine. Daughters of Decadence: Women Writers of the Fin-De-Siècle. Virago. 1993.

- Walsh, Jessica. “‘The Strangest Pain to Bear’: Corporeality and Fear of Insanity in Charlotte Mew’s Poetry.” Victorian Poetry, vol. 40, no. 3, 2002, pp. 217-240, https://www.jstor.org/stable/40004327.

- Warner, Val. Introduction. Charlotte Mew: Collected Poems and Prose, by Charlotte Mew, edited by Val Warner, Virago Press, 1982.

- Weir, Jane. Charlotte Mew: between the dome and the stars. Templar Monograph, 2007.

MLA citation:

Rodrigues, Catia. “Charlotte Mew (1869–1928),” Y90s Biographies. Yellow Nineties 2.0, edited by Lorraine Janzen Kooistra, Ryerson University Centre for Digital Humanities, 2021, https://1890s.ca/mew_bio/.