XML PDF

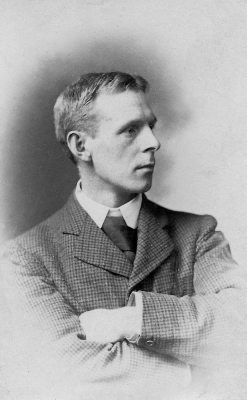

Charles H. Mackie

(1862 – 1920)

Charles Hodge Mackie was a distinguished Scottish painter and illustrator. He was born in Aldershot in 1862, to a military family, and died in Edinburgh in 1920, having been elected a member of the Royal Scottish Academy three years earlier. His career is full of interest, not least because of his friendships with French artists. He also made notable work in Italy, including a powerful coloured woodcut of Bassano Bridge, which drew on his interest in Japanese art. His ability as a graphic artist brought him to work with Patrick Geddes (1854-1932) on The Evergreen. Mackie’s role is immediately evident, as he designed the covers for all four issues (1895–1896). When Geddes called his publishing company “Patrick Geddes and Colleagues,” “Colleagues” was a carefully chosen word. It was meant to refer not simply to a group, but to members of a college, a scholarly and educational collective. Also in this sense, Mackie was a key colleague of Geddes’s in the late 1890s.

Geddes’s magazine title, The Evergreen, was both cultural and biological in reference, and Mackie contributed to both those aspects. His covers are strongly botanical in inspiration. In the first, for The Evergreen: Spring, the stem, leaves and flowers of an aloe curve up from its roots. In a letter written in February 1895 Geddes refers to that design, writing how pleased he is that Mackie has selected an aloe, taking it “as an omen that science and art are going to be better friends than ever” (NLS MS 10508a f 94). Geddes also uses an aloe-based tree of life to structure his own “Arbor Saeculorum,” or tree of the generations, an image that concludes the Spring volume. That design was drawn, to Geddes’s specification, by another artist central to the success of The Evergreen, John Duncan, whose style is unmistakable although he does not sign the work, for he clearly regards it as Geddes’s in conception.

The dense imagery of Mackie’s first Evergreen cover, the number of colours used, and the grade of the leather, caused production difficulties, so Mackie simplified his design to very good effect for the subsequent issues (Clark 39). His cover for the next issue, The Book of Autumn, retains the inspiration of the aloe but it now takes a central place as an unmistakable tree of life motif, closely related to the Geddes/Duncan “Arbor Saeculorum.” Mackie’s subsequent covers build on his design for Autumn. In his use of a Tree of Life motif Mackie echoed what William Morris and Walter Crane had been producing in England. Mackie’s work additionally points forward to the curvilinearity which would soon become a staple of Art Nouveau throughout Europe. By contrast, in its use of repeated thistles and Scottish heraldic lions rampant, Mackie’s recurrent back cover design emphasises The Evergreen’s Scottish place of origin.

Enduring respect for Mackie’s work is reflected in the fact that a version of his Autumn cover was used twenty-seven years after its first appearance. The book was The Wind in the Pines: A Celtic Miscellany, published by T. N. Foulis in 1922 to raise funds for Geddes’s Outlook Tower. It reused numerous illustrations from The Evergreen, including one by Mackie, “Lyart Leaves,” a beautiful woodcut first printed in the Autumn issue in 1895. “Lyart” is a Scots word referring to the fading and streaked leaves of autumn, and the title evokes the first line of Robert Burns’s poem “The Jolly Beggars”: “When lyart leaves bestrow the yird.” Therefore, this contribution has a strong Scots-language poetical reference, very much in the spirit of Burns’s literary predecessor Allan Ramsay, whose collection of Scots verse The Ever Green (1724) had been the cultural inspiration of Geddes’s title. “Lyart Leaves” also makes an international point, for in composition it leads to Japan, specifically to Hiroshige. For Mackie the link is via France, where he had been visiting fellow artists since 1892, among them Paul Sérusier and Paul Gauguin.

Mackie invited his friend Sérusier to contribute to the first volume of The Evergreen. Sérusier’s contribution, “Pastorale Bretonne” serves to underline the pan-Celtic aspect of the magazine, for the heritage of Brittany was very much part of the mix of material published by Geddes, not least at the prompting of The Evergreen’s literary advisor, William Sharp. Another friend, Mackie’s brother-in-law William Walls, contributed to the Spring volume. Walls’s drawing of lion cubs is a reminder of Geddes’s professional role as a biologist, and it looks forward to Geddes’s proposals for Edinburgh Zoo in 1913, carried out with the help of his daughter Norah and his son-in-law Frank Mears.

More significant from a fin-de-siècle aesthetic perspective is the contribution of another of Mackie’s friends, the artist Edwin Atkinson Hornel (1864-1933). That image, “Madame Chrysanthème,” can be found in The Book of Autumn and it again emphasizes the Japanese dimension. Hornel had just returned from Japan. The direct reference of Madame Chrysanthème is to Pierre Loti’s eponymous novel and, no doubt, to the opera by André Messager, which had been first performed in Paris in 1893. A decade later Loti’s story would influence Puccini’s Madama Butterfly (1904). That Japanese influence mediated by France can be found also in the work of another artist friend of Mackie, Robert Burns (1869–1938), who made a major contribution to The Evergreen, with seven full page works overall. Burns’s first work appears in the Spring issue. It is entitled “Natura Naturans,” meaning “nature naturing”—nature doing its thing, so to speak—a very spring-like notion. As with Mackie’s “Lyart Leaves,” which serves an equivalent for the Autumn issue, Hiroshige is again a key point of reference.

The Spring edition of The Evergreen gives a further clue to Geddes’s thinking by the inclusion of what had by this time become an identifier of Geddes’s publishing: a symbol of three flying doves. Those doves had appeared in the late 1880s in a stained-glass window at Riddle’s Court and in printed form they appear at least as early as 1888 (see Geddes, Every man his own art critic). Mackie had been known to Geddes through the Edinburgh Social Union from 1887 at the latest (Clark 35), so it seems quite likely that Mackie made the original drawing of these doves for Geddes’s publications. The doves stand for three words, which for Geddes summed up how one should approach the world, namely with “sympathy,” “synthesis” and “synergy:” engagement through the emotions, through the intellect, and through work. The immediate source for Geddes of that triad of ideas may have been the essay Body and Will, by the pioneering psychiatrist Henry Maudsley, which had been published in 1884. Sabine Krauss has pointed out that Geddes’s use of the terms “sympathy” and “synergy” would also have been related to his awareness of the eighteenth-century medical vitalist tradition in Montpellier, where he had studied, and where he would in due course establish his Scots College.

It will be clear then that Mackie’s role in The Evergreen was central, although he shared it with others, including Helen Hay (1867-1955) and John Duncan. In the Spring, Autumn, and Summer volumes Hay was entrusted with setting the scene for the text block of the magazine via the design of an almanac which showed the signs of the zodiac for the season, that is to say, Hay’s works were the first full-page images after Mackie’s cover design, and they should be seen in that significant and complementary light. Hay’s work, particularly for Autumn and Summer, has a fluidity of line which, as with Mackie’s covers, immediately links up to contemporary developments in Art Nouveau. It is also Hay who first gives The Evergreen its Celtic revival visual identity, through her adaptation of a Celtic letter “T,” which introduces the “Proem” to the Spring issue.

That initial also introduces an essay, “The Land of Lorne and the Satirists of Taynuilt,” by the outstanding Gaelic collector and translator Alexander Carmichael (1832-1912). His daughter, Ella Carmichael (1870-1928), followed her father to become one of Scotland’s foremost Celtic scholars, founding and editing The Celtic Review (1904–1916). Mackie’s continuing role in this milieu is clear, for around 1906 he painted Ella Carmichael’s portrait, now in the Department of Celtic and Scottish Studies at Edinburgh University (Clark 118). He shows her as a scholar at her desk, underlining her academic significance. There is an intriguing link back to The Evergreen, not through Mackie but through John Duncan, as the similarity between the portrait and the figure in Duncan’s “Anima Celtica,” which appeared in the first volume of The Evergreen, is striking (Macdonald, “Visual,” 142). (I am indebted to Abigail Burnyeat, then of Edinburgh University’s Celtic department, for drawing this similarity to my attention). Thus we find Ella Carmichael at the heart of The Evergreen milieu in 1895, which is presumably when she met Mackie.

A number of artists contributed head and tail pieces for the literature printed in The Evergreen. Mackie’s sister, Annie (c.1864–1934) was a prolific contributor of these decorative elements. The involvement of his sister is yet another reminder of his role in drawing together the network of artists working on this publication.

Mackie’s own contributions require further discussion. As noted, “Lyart Leaves” has a title in Scots. That linguistic reference is a key to understanding the place in The Evergreen of two other images by Mackie. Those images explore the cultural aspect of the title of The Evergreen, namely its reference to Allan Ramsay’s 1724 collection. The purpose of Ramsay’s Ever Green was to preserve old poetry in the Scots language, and it is precisely such material that we find Mackie illustrating, notably with his first full-page illustration in the spring issue, which refers to the ballad “Robene and Makyn” by Robert Henryson, who wrote in Scots during the second half of the fifteenth century, at a time when that language was the language of state. The second ballad Mackie illustrates is “By the Bonnie Banks o’ Fordie.” The story is of an outlaw who comes upon three sisters; he menaces each one, trying to make her marry him. The first two refuse and are killed. The third threatens him, invoking her absent brother; the outlaw then realizes that he himself is that brother. Aware that he has killed two of his sisters, he finally kills himself. A psychodynamic tale in the traditional manner of Scottish ballads, it had by that time been anthologised and analysed by Francis James Child. This American ballad collector had pointed out that it was a story common to both Scotland and Scandinavia, so one wonders if Geddes, via Mackie, is implying a wider northern European strand of revival here. Whatever the case, it is a memorable image which also survives in two painted versions: a sketch in the Hunterian Museum in Glasgow, and a finished oil painting in the collection of the City Art Centre in Edinburgh.

Mackie made several other works for The Evergreen. Three of them—“When the Girls Come out to Play” (Spring), “Hide and Seek” (Autumn), and “Chucks” (Summer)—were concerned with children’s play. Again, one feels Mackie and Geddes close in their thinking, for Geddes was an educator who advocated the European child-centred approaches of Froebel and Pestalozzi, and he would in due course compare the work of his younger contemporary, Maria Montessori, with the activities centred on his Outlook Tower in Edinburgh (Macdonald, Patrick Geddes’s Intellectual Origins, 156–158). In the work of all those thinkers we find an emphasis on the importance of play to children’s development. This is exactly what we see in Mackie’s images. His final image for the Evergreen is something of a contrast, yet, like his ballad works and his play subjects, it is closely linked to Geddes’s ideas. In The Book of Winter, Mackie shows woodcutters at work, “Felling Trees.” Here we see him returning to the overall seasonal nature of The Evergreen. In his role as professor of botany at University College Dundee, Geddes was already working on the foundations of what we now know as the discipline of ecology, and this image by Mackie should be seen in that context. We are not looking at a clear-felled forest, but an ecologically sustainable source of wood for a community economy. There is a further connection to Geddes, for this work for The Evergreen was adapted from one of Mackie’s murals made for Geddes’s flat in Ramsay Garden in Edinburgh. That underscores the integration of Geddes’s building and publishing projects, and the linked idea that the work done on both publications and buildings, albeit that it was directed by Geddes, was very much the work of Patrick Geddes “and colleagues.”

In conclusion, it is clear that in the 1880s and 1890s one of the most effective and significant of all the colleagues of Patrick Geddes was Charles Mackie. The reuse of one of Mackie’s Evergreen covers, both front and back, for the Celtic miscellany The Wind in the Pines in 1922 is a poignant reminder that he died, far too young—he was only in his late fifties—in 1920. His early death was a real loss to Scottish art.

©2024, Murdo Macdonald, Emeritus Professor of History of Scottish Art, University of Dundee, Scotland, United Kingdom.

Works Cited and Selected Publications about Mackie

- Clark, Pat. People Places and Piazzas: The Life and Art of Charles Hodge Mackie. Sansom, 2016.

- Fowle, Frances and Thomson, Belinda, eds. Patrick Geddes: The French Connection. The White Cockade, 2004.

- Geddes, Patrick. Every man his own art critic: Glasgow Exhibition 1888. William Brown and John Menzies, 1888.

- Geddes, Patrick. Letter to Charles Mackie, 4 February, 1895, from Ramsay Garden, University Hall, Edinburgh. National Library of Scotland (MS. 10508a f 94).

- Krauss, Sabine. “The Scots College: a stagecraft of Geddes’ thought.”

http://metagraphies.org/Sir-Patrick-Geddes/Sabine-Kraus_Scots-College-2014.pdf

- Maine, George F., ed. The Wind in the Pines: A Celtic Miscellany. T. N. Foulis, 1922.

- Maudsley, Henry. Body and Will. Appleton, 1884.

- Macdonald, Murdo. “The Visual Dimension of Carmina Gadelica.” The Life and Legacy of Alexander Carmichael, edited by D. U. Stiubhart. The Islands Book Trust, 2008, pp. 135–145.

- Macdonald, Murdo. Patrick Geddes’s Intellectual Origins. Edinburgh University Press, 2020.

MLA citation:

Macdonald, Murdo. “Charles H. Mackie (1862-1920),” Y90s Biographies. Yellow Nineties 2.0, edited by Lorraine Janzen Kooistra, Toronto Metropolitan University Centre for Digital Humanities, 2024. https://1890s.ca/mackie_bio/.