TABLE OF CONTENTS

No. 2

Front Cover. by Pamela Colman

Smith [i]

Untitled. [“The World of Imagination”], by William

Blake 2

Illustration by W.T. Horton 2

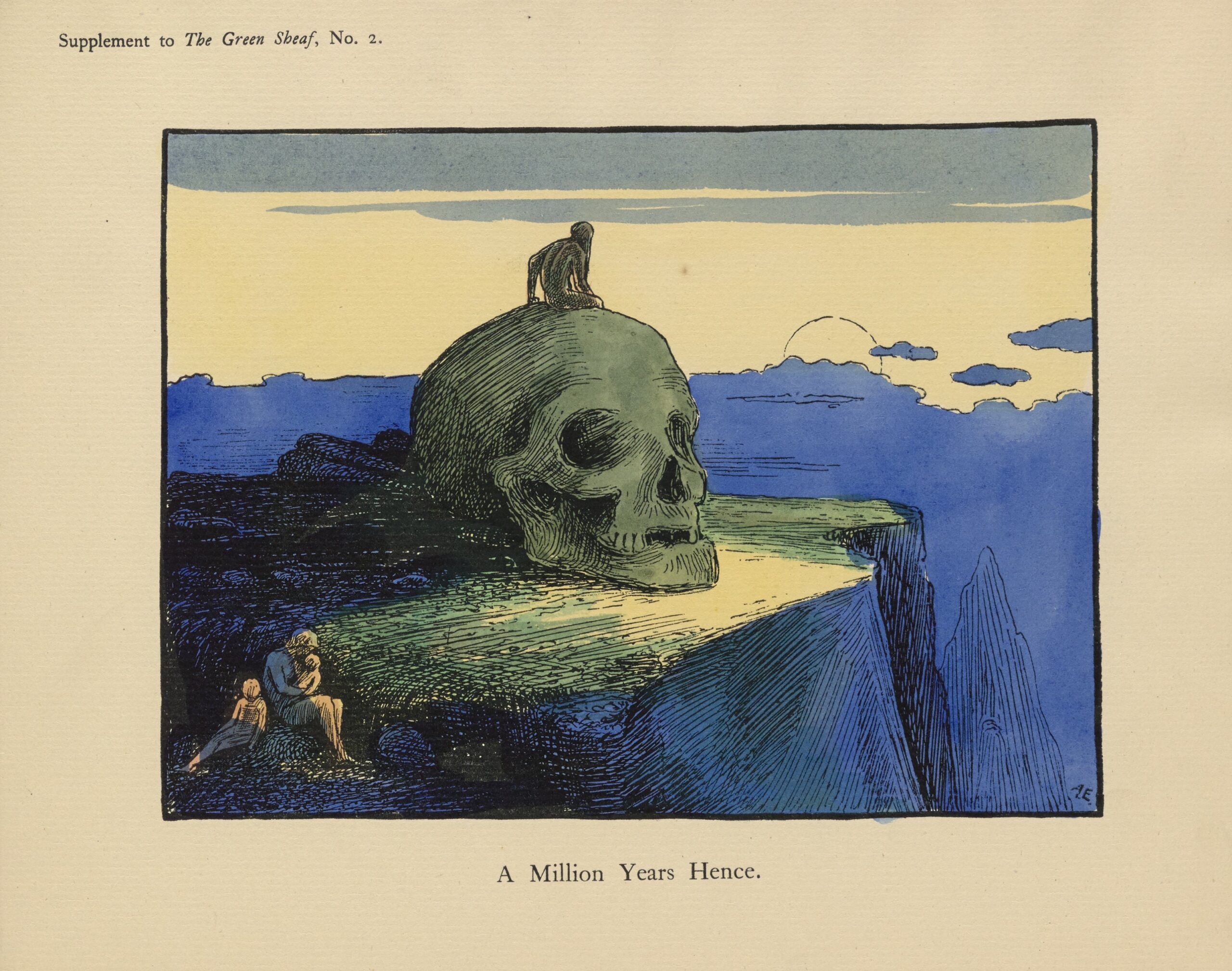

Illustrative Supplement. A

Million Years Hence, by A. E. np

At Departing, by Lucilla 3

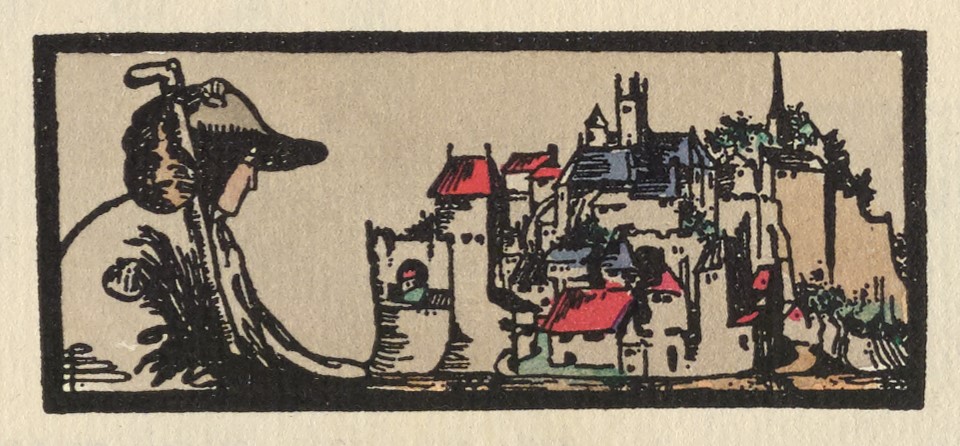

Illustration by Pamela Colman Smith 3

A Prayer to the Lord of Dreams, poem by Cecil

French 4

Illustration by Cecil French 4

Untitled [“Once in a Dream”], by Pamela Colman

Smith 5

Illustration by Pamela Colman Smith 5

Dream of the World’s End, by W.B. Yeats 6-7

A Dream on Inishmaan, by J.M.

Synge 8-9

Jan a Dreams, by John

Masefield 9-10

Illustration by Pamela Colman Smith 10

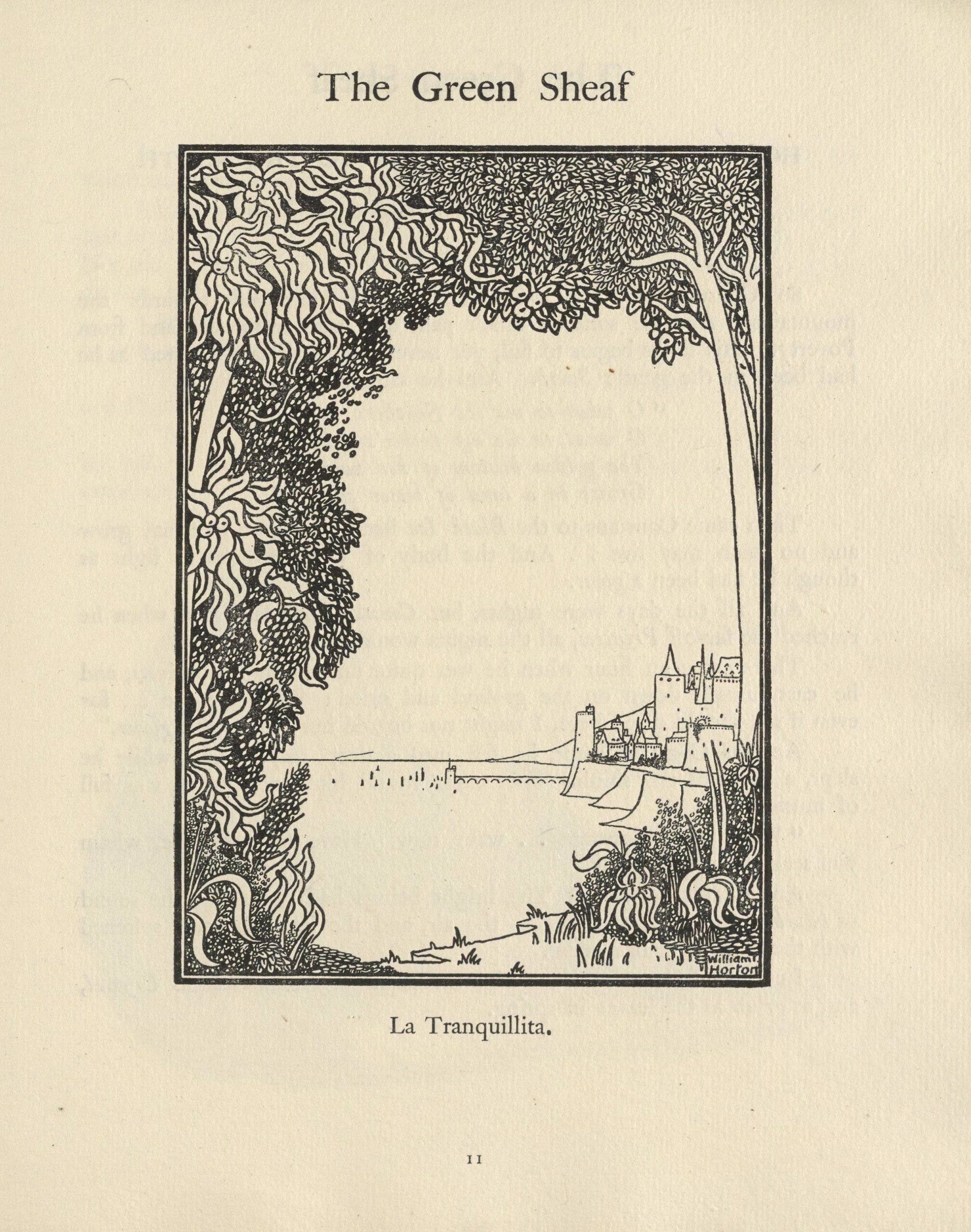

La Tranquillita, by W.T.

Horton 11

How Master Constans Went to the North, by Christopher St. John (Part II) 12-13

Illustration by Pamela Colman Smith 13

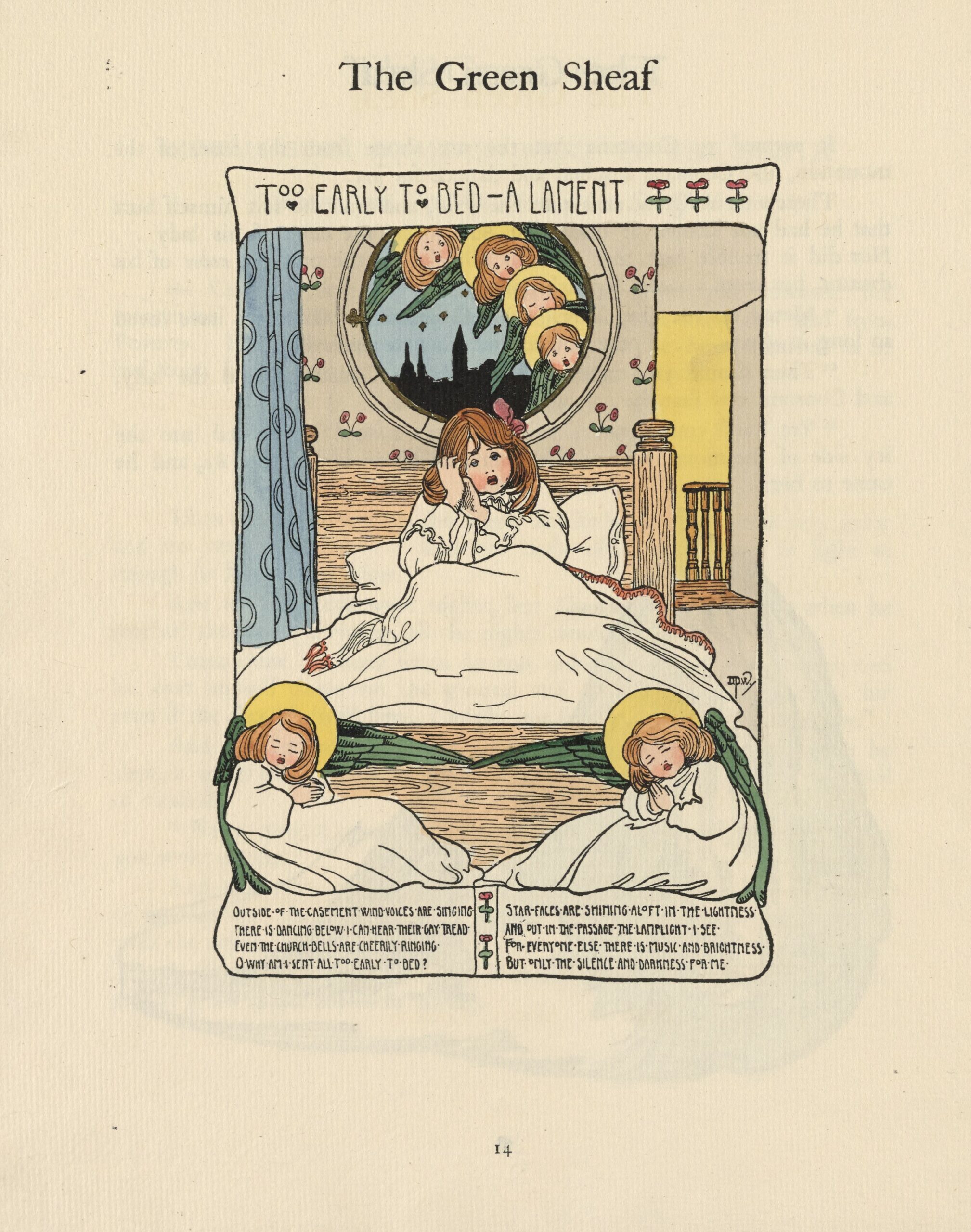

Too Early to Bed: A Lament, by Dorothy P. Ward 14

Advertisements 15-16

Advertisement for Edith Craig & Co.,

illustrated by Pamela Colman Smith 16

The world of imagination is the world of eternity. It is the divine

bosom into which we shall go after the death of the vegetated body.

The world of imagination is infinite and eternal, whereas the world

of generation or vegetation is finite and temporal.

There exist in that eternal world the eternal realities of everything

which we see reflected in this vegetable glass of nature.

William Blake.

AT DEPARTING.

As when we make a vagrant stay

In some old town, where drowsy time

As in the old-world steals away

In quiet, to the clock’s quaint chime,

And now ’tis come to our last day;

And late we saunter up and down,

Or walk on the embattled wall—

The gate-clasped girdle of the town—

Or once more visit the town-hall,

And churches of antique renown,

And take a fond and lingering leave,

As we pass on, of every part,

And while to say farewell we grieve,

We strive to get the whole by heart,

As dream, among our dreams to weave:

So when life’s end is near, we know,

And all our journeys we have been,

One hard last look we shall bestow—

Hoarding it’s dear and lightsome scene

For death’s long dark, where we must go.

Lucilla.

A PRAYER TO THE LORDS

OF DREAM

All things have conspired against me

To fill my heart with unrest.

Let me hide the world from remembrance;

To dream were surely best,

For the warring of flesh and spirit

Can only be drowned in dreams.

O Lords of the Silver Shadow,

Be tender with my dreams,

Lest even my dreams should conspire

To fill my heart with unrest.

Cecil French.

Once, in a dream, I saw a great church with a long narrow door,

and behind it rose a green hill. There was a garden on the top with

arches cut in box. The rooks cawed overhead. As I walked at the

foot of the hill I came to the church-yard, where many lilies grew; and

close by the church door was a sandstone tomb with two figures carved

on it. A foot of one of them began to wag.

Suddenly on the left there was a sound of solemn music—and many

spirits floated by. Mild faces had they; and every one carried a red

heart from which dropped a pearl—hung by a golden chain.

Then passing by they disappeared into the long blue door of the

church.

DREAM OF THE WORLD’S END

I have a way of giving myself long meaning dreams, by meditating

on a symbol when I go to sleep. Sometimes I use traditional symbols,

and sometimes I meditate upon some image which is only a symbol to

myself. A while ago I came to think of apple-blossom as an image of

the East and breaking day, and one night it brought me, not as I expected

a charming dream full of the mythology of sun-rise, but this grotesque

dream about the breaking of an eternal day.

I was going through a great city, it had some likeness to Paris about

Auteuil. It was night, but I saw a wild windy light in the sky, and knew

that dawn was coming in the middle of the night, and that it was the Last

Day. People were passing in a hurry, and going away from the light.

I was in a brake with other people, and presently the horses ran away.

They ran towards the light. We passed a workman who was making a

wall in his best clothes, and I knew that he was doing this because he

thought the Judge would look at him with more favourable eyes if he

were found busy. Then we saw two or three workmen with white faces

watching the sky by their unfinished work. Everybody now was a

workman, for it seemed to be a workman’s quarter, and there were not

many people running past us. Then I saw young workmen eating their

breakfast at a long table in a yard. They were eating raw bacon. I

understood somehow that they had thought “we may as well eat our

breakfast even though this is the Last Day”; but, that when they began

to cook it, they had thought, “it is not worth while to trouble about

cooking it.” All they needed was food, that they might live through

the Last Day calmly.

The Green Sheaf

After that, and now we seemed to have left the brake, though I did

not remember our leaving it, we came to a bridge over a wide river, and

the sky was very wild and bright, though I could not see any sun. All

in a moment I saw a number of parachutes descending, and a man in a

seedy black frock-coat came out of one of them, and began distributing

circulars. At the head of them was the name of a seller of patent

medicines, and we all understood the moment we saw the name, that

he was one of the most wicked of men, for he had put up great posters

that had spoiled many beautiful views. Each circular had printed upon it

a curse against this man, and a statement that a curse given at the end of

the world must of necessity weigh heavily with the Eternal Judge. These

curses called for the damnation of the patent medicine seller, and you were

asked to sign them at the bottom, undertaking at the same time to pay the

sum of one pound to the medicine seller if the end of the world had not

really come. I remember that the circular spoke of this “solemn

occasion,” but I do not recollect any other of the exact words. I awoke,

and was for some time in great terror, for it seemed to me that an

armed thief was hidden somewhere in the darkness of my room. Was

this some echo of what the Bible has said about “one who shall come as

a thief in the night?”

W.B. Yeats.

A DREAM ON INISHMAAN.

Some dreams I have had in a cottage near the Dun of Conchubar,

on the middle Island of Aran, seem to give strength to the opinion that

there is a psychic memory attached to certain neighbourhoods.

One night after moving among buildings with strangely intense light

upon them, I heard a faint rhythm of music beginning far away from me

on some stringed instrument.

It came closer to me, gradually increasing-in quickness and volume

with an irresistibly definite progression. When it was quite near the

sounds began to move in my nerves and blood, and to urge me to dance

with them.

I knew, even in my dream, that if I yielded to the sounds I would

be carried away to some moment of terrible agony, so I struggled to

remain quiet, holding my knees together with my hands.

The music increased again, sounding like the strings of harps tuned

to a forgotten scale, and having a resonance as searching as the strings of

the Cello.

Then the luring excitement became more powerful than my will, and

my limbs moved in spite of me.

In a moment I was swept away in a whirlwind of notes. My breath

and my thoughts and every impulse of my body became a form of the

dance, till I could not distinguish any more between the instruments and

the rhythm, and my own person or consciousness.

For a while it seemed an excitement that was filled with joy: then it

grew into an ecstacy where all existence was lost in a vortex of movement.

I could not think there had ever been a life beyond the whirling of the

dance.

The Green Sheaf

At last, with a sudden movement, the ecstacy turned to an agony and

rage. I struggled to free myself, but seemed only to increase the passion

of the steps I moved to. When I shrieked I could only echo the notes of

the rhythm.

Then, with a moment of incontrollable frenzy, I broke back to

consciousness, and awoke.

. . . . . . . . . .

I dragged myself, trembling, to the window of the cottage and

looked out. The moon was glittering across the bay, and there was no

sound anywhere on the island.

J.M. Synge.

JAN A DREAMS.

This dream, like all my in tenser dreams, commenced with a noise

as of the beating of many wings, the rush of water, and the roaring of

a sea-wind.

The tumult lasted for a few seconds, dying into a dry rustling as of

leaves scattered along a road in Autumn, and, with the subsidence of the

uproar, I woke, as it were, into the bright consciousness of vision. I

saw a multitude of dry leaves whirling, in a high wind, along a great

white road, and, in a little while, I saw that I, too, was shrunken to a

dry writhelled leaf; and then the great wind caught me, and swept me

forward among the others, and I knew, as I was blown along, that all

these flying leaves were human souls being hurried to Judgment.

After a long, tempestuous passage, this rout of leaves was blown into

a vast space, in the midst of which a white fire burned, with a great smoke

circling about it. At times this fire quickened and burned high, and then

the leaves leaped and danced in merry eddies. At times it guttered low

and then the leaves lay and trembled much as they will on the roads in

Autumn when the wind is too light to scatter them.

The Green Sheaf

In the great smoke about the fire the seven planets circled and sang,

and I knew that each note, each word, each letter of their song was a

human soul, for, at times, a dead leaf would be plucked from amongst

us and disappear among the smoke, becoming some minute part of the

great music of created things. Then I knew that the making of the

perfect music was beginning, and that the perfect song of the sailors,

and of the sea-creatures, and of the sea-weeds, and of the sea-fowl, and

of the sea-winds, and of the sea itself was about to be shapen and to

become a part of the song of the singing planets. And I, having loved the

sea, lay in my pile of leaves trembling with hope that I might be deemed

worthy of some part in that harmony.

The song began at last in a solemn paean of thunderous and glorious

words, like the running of a bright surf upon a beach. Then it trembled

down into a quiet lyric, like the chattering of a brook over pebbles;

then surged out again in a mournful andante that was like dawn, like a

grey twilight upon mountains. Then I knew that the making of a

tremendous word was in hand. A word which should signify and qualify

the sea; a vast word, gentle, tremulous and solemn, and I was plucked

forward (with a catch of joy in my heart, for I thought I had been deemed

unworthy) to become one poor letter in the great word, one frail note

in the perfect song, and then, as the completed music thundered and

throbbed among the planets, I woke.

John Masefield.

HOW MASTER CONSTANS WENT TO THE NORTH.

Heard and Told by Christopher St. John.

(Continued from No. i.)

So Constans left the warm South and journeyed towards the

mountains. And he suffered much pain and care from cold and from

Poverty. His limbs began to fail, yet never was he heavy-hearted as he

had been in the gentle South. And he sang always:

“O what to me the Southern air . .

O what to me my father’s gold . .

The golden blossom of her hair

Grows in a land of bitter cold.”. . .

Then came Constans to the Black Ice itself, where no tree may grow

and no man may live . . And the body of Constans was as light as

though he had been a ghost.

And all the days were nights, but Constans had faith that when he

reached the far-off Princess, all the nights would be days.

There came an hour when he was quite undone by his Sickness, and

he cast himself down on the ground and cried : “Let me die . . for

even if she should dwell here, I might not behold her face in this gloom.”

And as Constans wept, he fell into a deep sleep. And while he

slept, a troop of the shining ones came round him, and the air was full

of musick.

“Wake now, Constans . . wake now. Have faith, for she, whom

you seek, is near.”

And Constans awoke. The bright beings had gone, but the sound

of hautboys and flutes was still in the air, and the icy wind was softened

with the smell of frankincense.

In front of Constans was a high mountain of ice as clear as Crystal,

and as green as the leaves in spring.

The Green Sheaf

It seemed to Constans that the sun shone from the heart of the

mountain, and Constans laughed and danced for joy.

Therewith he drew nearer to the Hill, and now he felt himself hurt

that he had not known at once that Sun to be the hair of his lady . .

Nor did it trouble him that she was not clad in the princely robes of his

dreams, but wore a mean beggar’s garment.

“Mercy on me, my lady,” cried Constans. “Since we have loved

so long in dream . . I pray you tell me how to reach you.”

“Then should you taste of death Master Constans,” said the lady,

and Constans saw that she was whiter than snow.

“Yet I will come nearer,” said Constans. And he walked into the

icy side of the mountain, and his faith like flame melted the ice, and he

came to her.

ADVERTISEMENTS.

IN THE SEVEN WOODS: Poems chiefly of the Irish Heroic Age.

By W. B. Yeats. Hand-printed (Rubricated) by Elizabeth Corbet Yeats. Published

at the Dún Emer Press, Dundrum, Co. Dublin. Crown 8vo, 10s. 6d. net. [Shortly.

From ELKIN MATHEWS’ LIST.

THE GOLDEN VANITY AND THE GREEN BED: Words and

Music of Two Old English Ballads. With Pictures in Colour by Pamela Colman Smith.

4to, 7s. 6d. net.

“The illustrations are highly spirited in treatment. They exhibit a strong decorative

sense on the part of the

artist, the colour scheme being remarkably bold and well ‘harmonised.’”—Studio.

WIDDICOMBE FAIR: A series of 13 Coloured Drawings to this Old

West Country Ballad. By Pamela Colman Smith. 4to, in portofolio, 10s. 6d. net.

A BROAD SHEET—For the Year 1902: With Pictures by Pamela

Colman Smith and Jack B. Yeats. Hand-coloured. Twelve numbers, post free,

12s. 6d. net. A portfolio may be had at 2s. net.

Fourth Edition Now Ready.

THE WIND AMONG THE REEDS. By W. B. Yeats. Crown

8vo, 3s. 6d. net.

SONGS OF LUCILLA. Crown 8vo, 3s 6d. net.

“The author of these verses shows a very considerable power of writing. She has not

merely the accom-

plishments of style and melody, but has a way of attacking her subject which shows

real power, the power to think

as well as to turn that wonderful verbal kaleidoscope which is the heritage of all

the poets of this generation. . . .

[The poem ‘A Drunken Satyr’] is full of the spirit of Keats, and suggests all through

Keats’ way of writing, but

nevertheless it arrests the attention as only a poem of originality can. Above all,

it shows promise.”—Spectator.

Published by ELKIN MATHEWS, Vigo Street,

Nigh the Albany, London.

The Green Sheaf

MLA citation:

The Green Sheaf, No. 2, 1903. Green Sheaf Digital Edition, edited by Lorraine Janzen Kooistra. Yellow Nineties 2.0, Toronto Metropolitan University Centre for Digital Humanities, 2022. https://1890s.ca/gsv2_all/