TABLE OF CONTENTS

No. 13

Front Cover, by Pamela Colman Smith [i]

Untitled. [“Around the earth”], by Dorothy Ward 2

Illustration by Dorothy Ward

The Galley Slave, by Alix Egerton 3

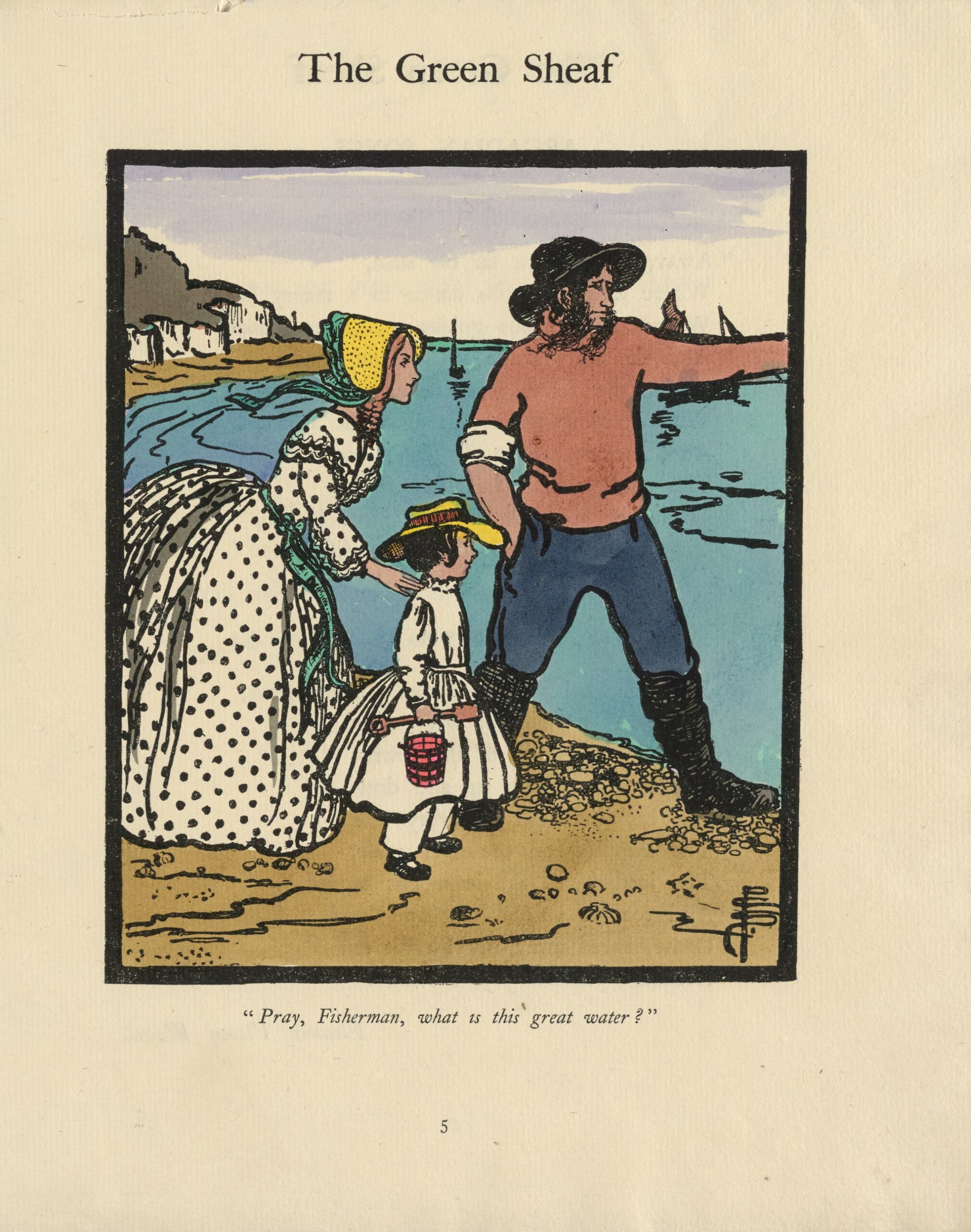

Charles at the Seaside, by Mrs. [Anna] Barbauld 4

Supplement. [i-viii]

A Horror of the House of Dreams, by F. York-Powell [i-vi]

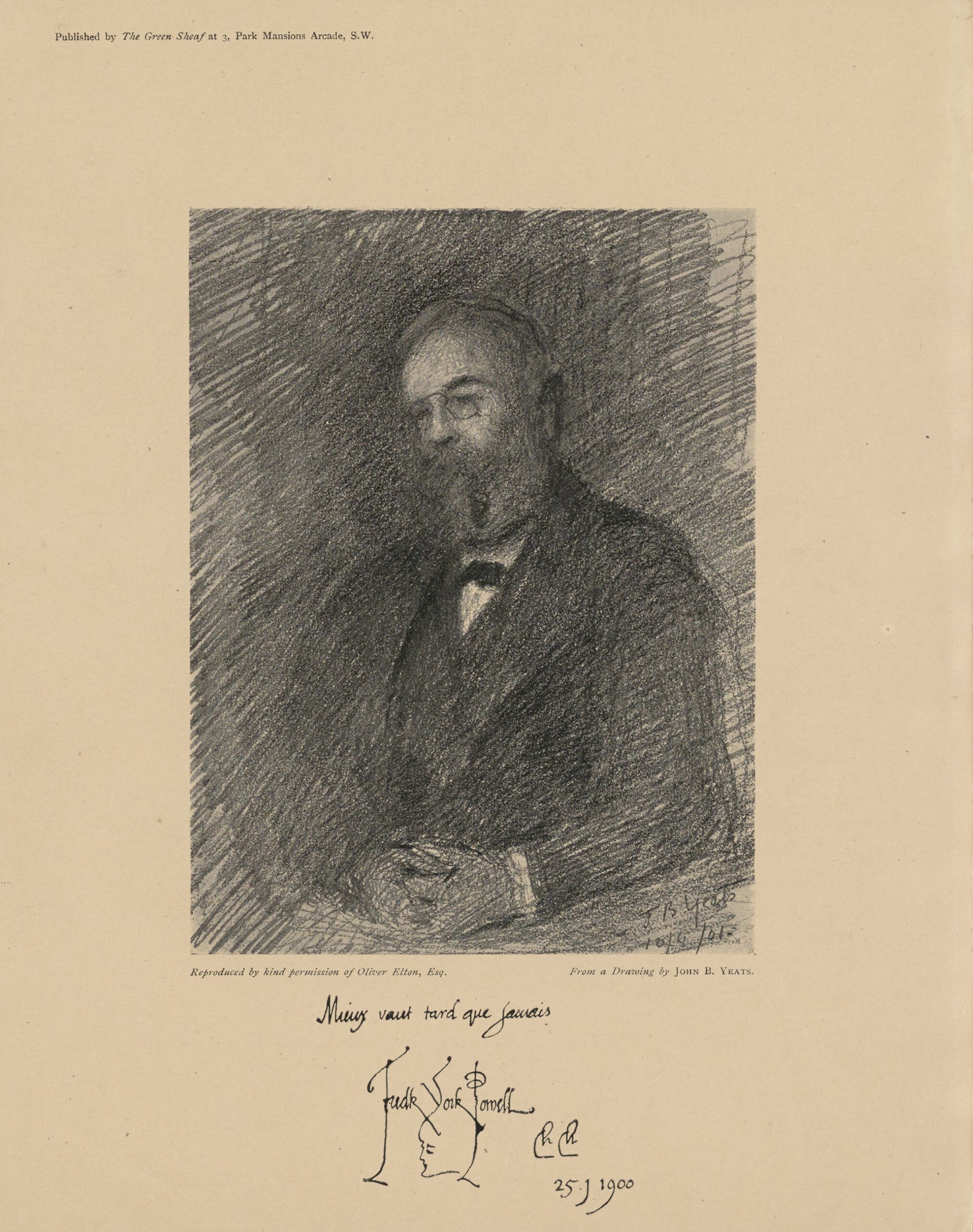

Sketch of F. York-Powell by John Butler Yeats np

Frederick York-Powell: A Reminiscence, by John Todhunter [v-vii]

Advertisement for the Green Sheaf Shop, Knightsbridge, illustrated by Pamela Colman Smith [viii]

“Pray, Fisherman, What is this Great Water?,” by Pamela Colman Smith 5

Arcadian Songs, by Eleanor Vicocq Ward 6

The Wind, by Evelyn Garnaut Smalley 7

Page decoration by Pamela Colman Smith 7

Untitled. [“Alfred’s Aunt”], by Reginald Rigby 8

Illustration by Reginald Rigby 8

THE GALLEY SLAVE.

The wind is softly sighing round the house,

Tapping with gentle finger on the pane,

The scuttering footsteps of a tiny mouse

Rise in the distance and depart again.

A bird turns in its nest beneath the eaves

And twitters as it falls again to sleep;

Two roses kiss beneath the sheltering leaves,

An owl floats overhead with noiseless sweep.

A grasshopper chirps in the field below,

A moth goes fluttering round your bedroom wall,

Night’s silence and her voices come and go,

Her mystery and magic, on you fall.

All this you hear, but yet, alas, no more,

Although my heart is beating at your door.

Alix Egerton.

CHARLES AT THE SEASIDE.

“Pray, Fisherman, what is this great water?” “It is the sea; did you

never hear of the sea?” “What! Is this great water, the same sea that is in

our map at home?” “Yes, it is.” “Well, this is very strange! We

are come to the sea that is in our map. I can lay my finger over it.”

“Yes; it is little in the map; the towns are little, and the rivers are

little.”

“Pray, Fisherman, is there anything on the other side of this sea?”

“Yes; fields, and towns, and people. Will you go and see them?”

“I should like to go very well; but how must we do to get over, for

there is no bridge here?” “Do you not see those great wooden boxes

that swim upon the water?” “They are bigger than all Papa’s house.

There are tall poles in the middle, as high as a tree.” “Those are masts.

See how they are spreading the sails.” “They are like wings. These

wooden boxes are like houses with wings.” “Yes, and I will tell you

what, little boy! they are made on purpose to go over the sea; and the

wind blows them along faster than a horse can trot.” “What do they call

them?” “They call them ships.” “What have those men in the ships

got on?” “They have jackets and trousers on, and checked shirts.

They are sailors. I think we must make you a sailor; and then instead

of breeches you must have a pair of trousers. Do you see that sailor, how

he climbs up the ropes? He is very nimble. He runs up like a monkey.

Now he is at the top of the mast. How little he looks! But we must

get in. Come, make haste; they will not stay for us.”

Mrs. Barbauld.

A HORROR OF THE HOUSE OF

DREAMS.

I was staying for the first time at the country house of an old friend, whom I had

not seen for years. It was late in the evening, and we were sitting in the smoking-

room having a last pipe together before we went to bed. The room was panelled

with dark wood, and the furniture was old. I felt sleepy as my friend talked, and

gave him but short answers. Gradually I became conscious of an unpleasant

feeling of vague discomfort, for which I could not account. This grew upon me

more and more, till my sleepiness fell off me, and I began to wish that my friend

would propose our going to bed. A feeling of fear, which seemed in some

mysterious way to grow into a sense of something uncanny in the room itself, was,

in fact, gradually mastering me.

As I was trying to find some excuse for escaping, there was a knock at the

door, and my friend’s butler came in with spirits and tumblers. He was an oldish

man, who had been long in the family. We spoke to him, and my friend asked

him to sit down and have a glass of spirits and water with us, which he did. After

a little more talk we got up, intending to go to bed. The smoking-room was on

the first floor, at one end of a long drawing-room, into which it opened by a door,

a second door leading to a landing. We all went out on to this landing, where

the candles were; but as I was turning to the great oak staircase, my friend

suggested that we should go and say good-night to his aunt. I agreed, and we

went back into the smoking-room, and through the long drawing-room, which I

could see by the moonlight, the blinds being up in three or four tall windows,

though the moon itself was not visible. As we passed these windows I could see

the gardens, and a misty meadow beyond, against which the small, black, clipped

trees of the terrace showed hard and distinct. The furniture was of the beginning

of the nineteenth century—a harp, a large old-fashioned piano, chairs with flowered

tapestry seats, and a light carpet with large flowers. There was a white marble

mantelpiece, and the walls were painted in dark reddish-brown distemper, which

seemed a little faded. A few water-colours were hung at wide intervals upon the

walls.

Passing through this room close under the windows, and through a door

opposite to that by which we had entered, we came into a boudoir, just like the

smoking-room in shape and size, but furnished in the same old-fashioned style as

the drawing-room, and lit by two large windows, in one of which the blinds were

up. There were two candles burning on a little table, and a fire in the grate, in

front of which sat a pleasant-Iooking old lady with grey hair, in a lace cap and

purplish satin dress. A maid with a baby in her arms was sitting at the side of

the room opposite the door by which we had come in. I was introduced to the

old lady, sat down beside her, and we began talking, our faces to the fire, our

backs to the candles.

I had totally forgotten my feeling of discomfort, and was interested in our

conversation, when 1 noticed that the light in the room had become dim. The

glow died out of the fire, leaving it dull; and when I looked round the candle

flames had dwindled to the blue. I stood up, and saw my friend and the butler

standing together at the door, holding it ajar, and craning their heads round it to

look into the drawing-room, whence a bright light proceeded and fell flatly about

their feet. I ran up to them. “What is it?” I asked; but they motioned me

back. “You had better not look!” said my friend, in a curious, tuneless voice,

tense with suppressed irritation. “Oh, nonsense!” said I, “I want to see!”

Pushing past them, I went into the drawing-room ; and there, a few paces in front

of me, I saw a spare old gentleman in a dress of the time of George II., pale blue

coat, pale yellow breeches, silk stockings, buckled shoes, and ruffled wrists. He

stood in a pantaloon-like attitude, in his right hand a thin, polished, brown

walking-stick, which seemed to me of about the fineness of the thin end of a

billiard cue. 1 could see nothing of his face; but the end of his nose, which must

have been long, was just visible beyond the profile of his cheek. He stood in the

midst of an oval of light on the floor, very like that gleam which I have since

noticed thrown by a tricycle lamp upon a dark road, but sharper in its outlines.

He walked slowly along to the wall, his footsteps making no sound; and as

he drew near the side of the room, I observed that wherever the oval of light passed

across the floor, or mounted up the wall, the decoration changed to an earlier

style. The wall within the light now appeared a pale green, with panels of pale

tinted landscape, bordered by rococo scroll work. In the centre, at the bottom of

a panel, I could see the figure of a nymph reclining among reeds. The old gentle-

man stood before this panel, raised his stick, and rapped the centre of the tuft of

reeds with such irritable violence that the stick snapped, and about eight inches

of

it fell on the floor; but all this without making the slightest noise. Immediately

afterwards the light went out, and the decoration fell back into the flat red tint

of

the distemper. But I had kept my eyes fixed on the exact spot upon which the

old gentleman had rapped, and, running forward to the wall, 1 clapped my hand

on the place, which now showed like a grease spot, a little darker than the rest of

the wall. “There, there!” I cried out; “if you break into the wall to-morrow you

are sure to find something.”

I turned excitedly towards my friend,, who I thought had followed me; but I

saw that he was still standing with the butler half behind the door. Between me

and them I could see no one; only, on the floor between me and them, flitting silently

about, were two small ovals of light. I knew that these marked the

soundless footsteps of the old gentleman, now become invisible.

A horror, such as I had felt in the smoking-room, now suddenly again fell

upon me; but in far greater force. How I got back, past those gleaming footprints

as they moved silently about—back to the boudoir—I don’t know. I only

remember that I found myself standing by the fire, near the old lady, who had

risen to her feet. I kept looking round at the window, wondering whether it would

be possible to escape through it; but I judged the height, at least twenty feet from

the ground, too great for such a venture.

My friend and the butler were still at the door; and again I saw the great

flat light, now brighter than ever, at their feet. They were as terror-stricken as

I

was myself. “What shall we do?” I heard someone say; and after a minute of

silence my friend and the old lady began reciting with earnest but shaken voices

some versicles of the Litany.

For a moment I thought perhaps their prayers might avail us, for the light

seemed to ebb from the doorway; but at the end of the second verse I was com-

pletely panic-stricken as I heard the words, “Good Lord, deliver us!” slowly and

distinctly repeated in a grating, mocking, old man’s voice, which came from the

other room; and, with this venomous echo still in my ears, I woke.

F. York-Powell.

FREDERICK YORK-POWELL

A REMINISENCE

I have given York-Powell’s remarkable dream as nearly as possible in his own

words, just as I took it down some years ago from his dictation.

By his death Oxford has lost one of its most distinguished scholars; and

his host of friends a friend whose loss leaves the world a narrower pinfold

than it seemed while he lived and laughed in it; for his laugh was like

the laugh of a Viking—a courage-kindling laugh. It expanded your soul; and

though like Hamlet you be might be “bounded in a nutshell,” it made you

feel yourself for a moment “a king of infinite space.”

Never surely was there such an unconventional Don of Christchurch,

such an unusual Regius Professor of History. He was not of the ordinary

Oxford pattern; but a man of vigorous personality, who looked at everything

from his own standpoint, cared little for traditional. standards, and went his

own way. He was no mere book-man, though he knew his books well; no

mere specialist, though well skilled in his own special subject. He was

interested in life all round, and was an encyclopaedia of minute knowledge

of the most varied kind—a man who might have passed with honours an

examination on things in general.

He had a very large circle of friends in all ranks of life, and of all

shades of religious and political opinion; and he was himself a most faithful

and helpful friend, always ready to give and receive freely. He had his

narrownesses and prejudices, no doubt; but he had something of that large

sympathy which enabled Goethe to get at what was best in those whom he

met. And from books, as from men, he could rapidly assimilate what was of

most vital interest to himself. He would spend half an hour in your study,

prowl round your shelves, and while talking skim through the pages of a

book here and there, and know more about it when he put it back than a slower-

brained man would by reading it from cover to cover. His memory was quick

to seize and slow to forget, because his interest was always intense in what

interested him, and most things did.

As men of all classes may expect to meet in heaven, so did they sometimes

actually meet in York-Powell’s rooms at Oxford. Once a friend, calling to

see him, found him in animated conversation’ with an intellectual chimney-

sweep, a socialist, and a great crony of his. On another occasion, as a distin-

guished art-critic told me, he came to dinner, found York-Powell had forgotten

the appointment, and had to entertain a Dean and an Anarchist until their host

arrived late and formally introduced them.

As a Professor of History, York-Powell looked upon his materials as

Browning upon his “square old yellow book,” as:

“. . . . pure crude fact,

Secreted from man’s life when hearts beat hard,

And brains high-blooded ticked; ”

and went straight through the theories of the historic web-spinner to the

contemporary documents, which he handled with sympathetic imagination

when he wrote anything himself, which he too seldom did; and his interest

in literature, art, handicrafts, and sports—such as yachting, boxing, fencing—

was no less intense than in that record of the lives of nations and the deeds

of men of action which we call History.

He was a man vividly alive to the last; and his influence on the younger

men who came in contact with him at the University and elsewhere was, above

all else, an inspiriting one. He did not believe much in the intellectual

activities of the modern woman; but he was always ready to help the girls

as well as the boys in their studies. He not merely gave all who asked for

it information; he kindled a thirst for knowledge in those capable of thirsting.

It was good to have known him.

John Todhunter.

ARCADIAN SONGS

PHYLLIS.

“Away, away, to a far off land,

Where wood nymphs dance in a merry band,

Where the glorious golden sunshine spreads,

And the leafy shade is o’er our heads.

Where the velvet grass beneath our feet

With budding flowers is all made sweet,

And, sheltered from the sun’s hot rays,

The cooling fountain softly plays,

While the air with thrilling birds is rife,

That chant the joys of country life.”

CORYDON.

“Leave far behind the smoke-grimed street,

The endless tramp of weary feet,

The toiling traffic of the town,

That’s ever moving up and down,

The buildings tall on every side,

The shipping on the river wide

The jostling of the impatient crowd,

And roar of voices long and loud.

Come, speed away my Phyllis fair

Arcadia’s peaceful joys to share.”

Eleanor Vicocq Ward.

THE WIND.

Though east winds whirl and cloudland lowers

And wild wild waves are white with spray,

Oh who could seek to shun the showers,

Oh who would wish the wind away?

After the rain we’ll find fresh flowers,

The storm has left the leaves at play;

Oh who could seek to shun the showers,

Oh who would wish the wind away?

Evelyn Garnaut Smalley.

MLA citation:

The Green Sheaf, No. 13, 1904. Green Sheaf Digital Edition, edited by Lorraine Janzen Kooistra. Yellow Nineties 2.0, Toronto Metropolitan University Centre for Digital Humanities, 2022. https://1890s.ca/gsv13_all/