“A Paper of Her Own”: Pamela Colman Smith’s The Green Sheaf (1903-1904)

n May 1903, The Review of Reviews published a brief item on “London Editors Who Are Women,” excerpted from a leading article in Cassell’s Magazine. The author, Rudolph de Cordova, identifies nine female editors then based in London: Rachel Beer (The Sunday Times); Hulda Friederichs (Westminster Budget); Ada S. Ballin (Baby and Womanhood); Ethel Gordon Fenwick (Nursing Record); J. Heale (Myra’s Journal); Rita Shell (The Lady); E. Macdonald (Ladies’ Field); Emma Sarah Williamson (The Onlooker); and Pamela Colman Smith (The Green Sheaf). De Cordova goes on to name five women who shared, “when they were editors, the distinction of owning her own paper,” but neglects to include Smith among them (“London” 485). Pamela Colman Smith (1878-1951), however, occupies a unique place in this distinctive group of early twentieth-century women who edited the periodicals they owned and managed. In addition to editing and publishing The Green Sheaf (1903-4), Smith contributed to both its literary and artistic contents. The periodical was available by mail-order through transatlantic subscriptions and at a few local places. In London, consumers could buy The Green Sheaf in Vigo Street at the bookshop of Elkin Mathews and (after the 4th issue) at 14 Milborne Grove, Smith’s premises. After the 7th issue, The Green Sheaf could also be purchased at Brentano’s Bookstore in Union Square, New York.

Unlike her sister editors, who were pioneers in the burgeoning mainstream press, Smith aimed The Green Sheaf at a niche market interested in fine printing, folklore, and the mysticism associated with the Irish Celtic movement. The Green Sheaf contested the industrial methods of the commercial press through an arts-and-crafts production model, which included hand-made paper and hand-coloured illustrations. Like other arts-and-crafts little magazines such as The Dial (1889-1897) and The Evergreen (1895-96/7), The Green Sheaf was produced by a coterie of like-minded artists and writers, had an explicit manifesto and a short print run, and was linked with international networks of modern art. In the largely male-dominated world of little magazines in fin-de-siècle Great Britain, The Green Sheaf is remarkable for its female leadership, eclectic content, and artisanal design. Its acknowledged place among other little magazines of the period is long overdue.

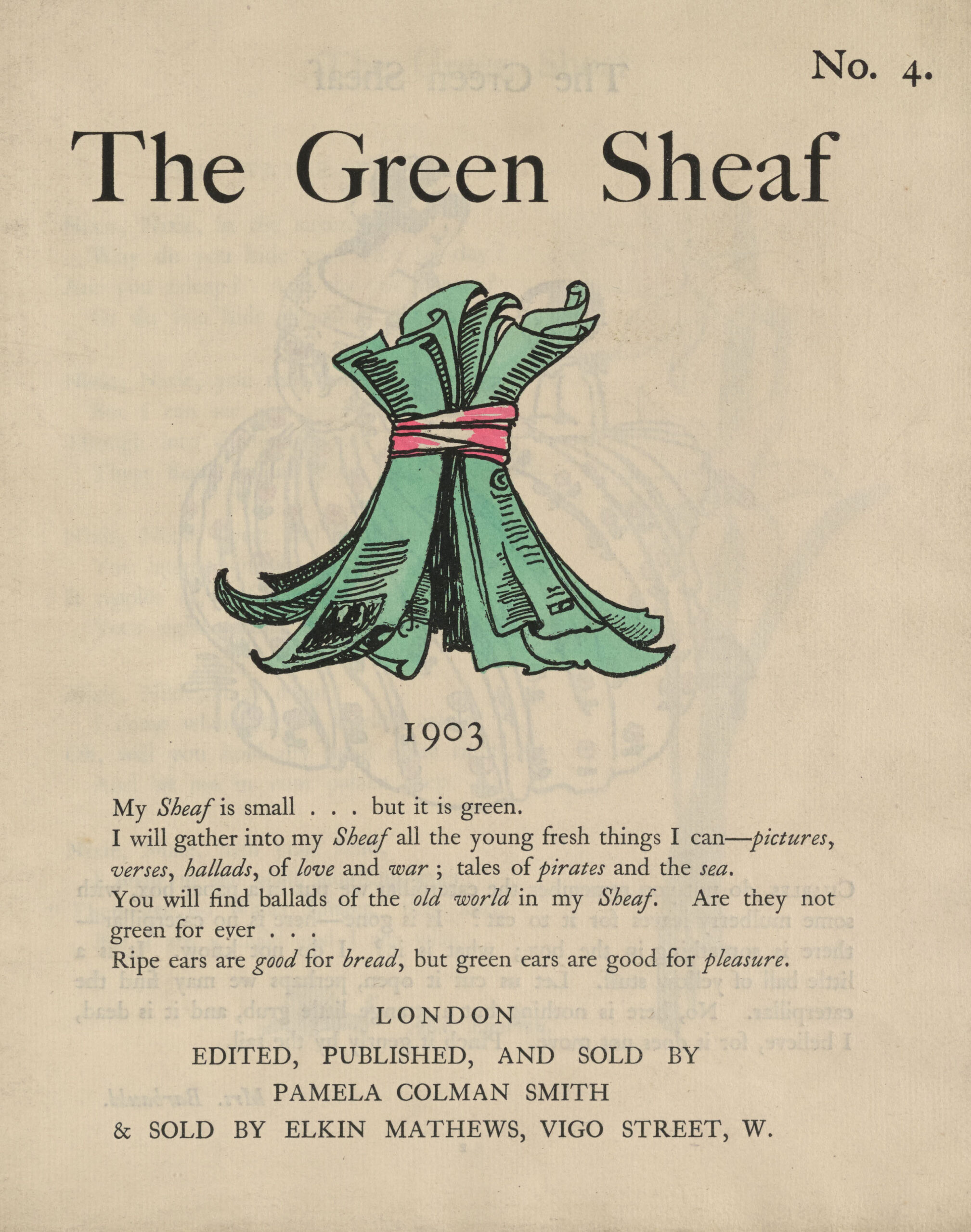

In addition to The Green Sheaf’s Celtic affiliations, Pamela Colman Smith, who was not Irish, brought a transnational interest in fluidity and border crossing to the magazine. This is not surprising in someone who claimed to have crossed the Atlantic 25 times by the time she was 22 (Armstrong 526). Assuming the name “Pixie” given to her by Victorian actress Ellen Terry, Smith cultivated an “in-between” persona whose fluid identity encompassed the Irish pixie, the Jamaican Anansi (a trickster figure in Caribbean folklore), and even, on occasion, the Japanese girl (O’Connor, “Primitivism” 158, 167). Born to American parents in London, Smith triangulated among the United Kingdom, Jamaica, and New York throughout her formative years. Living in Kingston as a young girl, she enjoyed Jamaican folklore in oral culture, and Irish mythology and the ballad tradition in print culture. These twin influences can be seen throughout her career, coupled with the Japanese design principles and colour theory she developed as a student of Arthur Wesley Dow at the Pratt Institute in Brooklyn. Arts-and-crafts ideals were embedded in the school’s curriculum, and Smith developed a method of hand-colouring her distinctively flat, black-bounded designs using stencils (Parsons 358). The artisanal Green Sheaf enabled Smith to bring together her interests, influences, and inspirations. The magazine’s manifesto identified “pictures, verses, ballads of love and war; tales of pirates and the sea” as its subject matter. Appearing with the back matter in early issues, this manifesto was published prominently on the cover, along with the self-referential Green Sheaf iconography, from volumes four through thirteen (fig. 1).

While The Green Sheaf was the first publication over which Pamela Colman Smith exercised sole control, she had previously co-edited A Broad Sheet, and had made significant contributions to both The Kensington: A Magazine of Art, Literature and the Drama and A Celtic Christmas, the seasonal supplement to The Irish Homestead. The Kensington had a brief print run of seven monthly issues in 1901. A regular feature on “The Drama” by Christopher St. John (born Christabel Marshall) typically focused on Ellen Terry’s performances at the Lyceum Theatre in London. Terry was the mother of St. John’s partner Edith Craig; all three women were close with Pamela Colman Smith personally and professionally. Interested in stage and costume design from her youth, when she first created a toy theatre and began performing its plays in Jamaica and New York, Smith went on to design sets and costumes for Henry Irving and Ellen Terry at the Lyceum, W.B. Yeats’s early plays for the Irish Literary Society, and Craig’s suffrage plays for the Pioneer Players. Smith’s earliest commercial illustration work included hand-coloured prints of scenes from Shakespeare, which she sold through the Macbeth Gallery on Fifth Avenue in New York, and a calendar featuring Shakespeare’s Heroines, commissioned by R. H. Russell in 1899. She also produced a souvenir booklet for her cousin, William Gillette, an actor renowned for his portrayal of Sherlock Holmes on the American stage, and a commemorative pamphlet celebrating Henry Irving and Ellen Terry (Kaplan et al, 25 and 27).

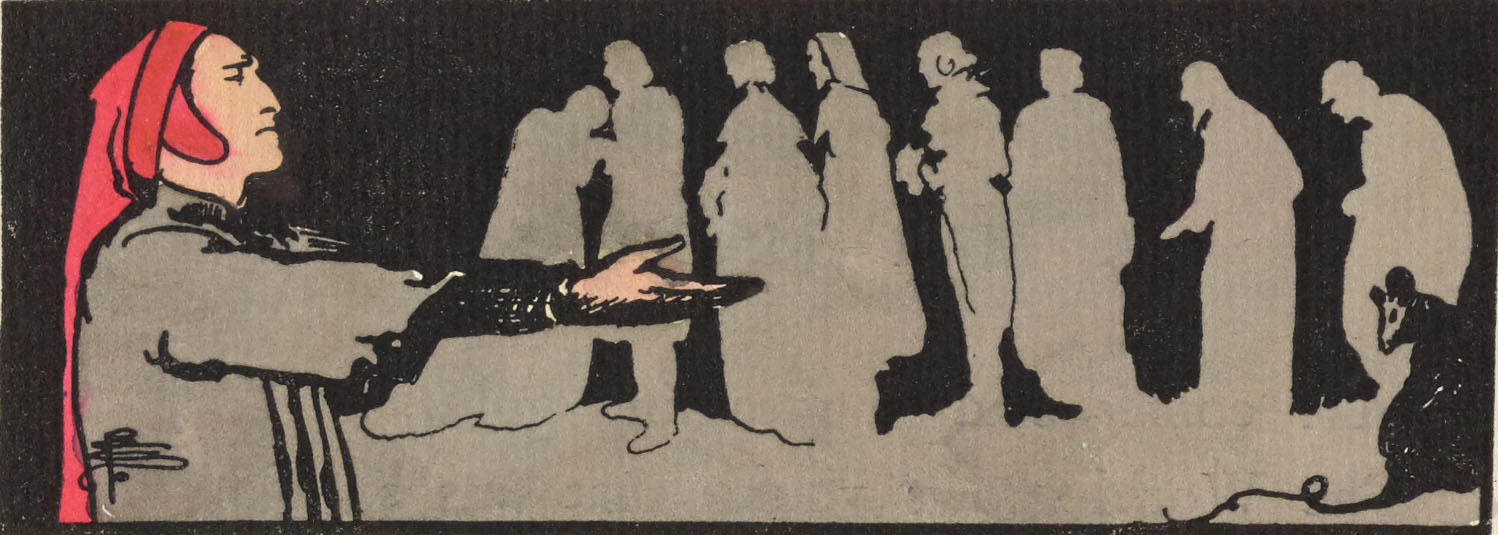

Smith’s theatrical network is evident in both The Green Sheaf’s literary and artistic contents and its advertising pages. The back matter of every issue promotes Edith Craig’s costume shop and hand-coloured prints by Pamela Colman Smith of Ellen Terry in various roles. Smith advised art students that “the stage is a great school—or should be—to the illustrator” (“Should the Art Student Think?” 417), and her own illustrative designs for The Green Sheaf serve as object lessons for this approach. Typically, she positions the viewer from a particular vantage point, looking on a tableau frozen in the midst of action and narrative (fig. 2). In her illustration for Mary Brown’s “Lament of the Lyceum Rat,” for example, Smith depicts Henry Irving as Dante, stretching out his arm before a ghostly cast of himself and leading lady Ellen Terry silhouetted in an array of former roles. Combining the illustrative and the decorative, Smith shows the over-sized, titular rat emerging in profile from the dramatic black background, mirroring the bent back of one of Irving’s characters. The Lyceum rat’s tail in the right corner offsets Pamela Colman Smith’s distinctive monogram flourish in the left, possibly as an impish corrective to any possible “mawkish weeds of sugar-sweet sentimentality,” which Smith thought all artists ought to avoid (Smith, “Protest”). In September 1903 this image was reproduced in an article in the American magazine The Reader, which highlighted the topical poignancy of its appearance “at the time Sir Henry Irving was giving his farewell performances at the old Lyceum Theatre, now being torn down” (“Writers and Readers,” 332).

Smith’s involvement in A Celtic Christmas, a seasonal supplement to the Dublin-based Irish Homestead, was an outcome of her expanding Irish networks after meeting members of the Yeats family in spring of 1901. Her first illustrations for this magazine were published in the same year; later, her design representing the Celtic spirit as a female figure overlaid on the map of Ireland graced the magazine’s cover for five consecutive seasons (1904-8). In 1901 Smith also became involved with the Dun Emer Guild, the women-and-craft-focused enterprise established by Evelyn Gleeson and Elizabeth and Lily Yeats. Smith gave advice on hand printing and provided some designs for banners, book-plates, cards, and textiles (Bowe and Cumming 123-25). She also became close to the two Yeats brothers at this time. At W.B. Yeats’s invitation, Smith joined the Isis-Urania Temple of the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn, a secret society devoted to the study and practice of the occult. In 1902, she and Jack Yeats began to co-edit A Broad Sheet, published by Elkin Mathews in monthly issues. A single page of hand-laid paper, vibrant with hand-coloured images interspersed with verses, A Broad Sheet shared the arts-and-crafts values of The Green Sheaf, as well as some of its thematic interests and contributors. After a year of working together, the collaboration began to fray, and Pamela Colman Smith decided, as The Reader succinctly observed, to start “a paper of her own” (“Writers” 332).

Cannily, Smith used the Broad Sheet’s mailing list to disseminate The Green Sheaf’s Prospectus and invite subscriptions from a transatlantic clientele:

You have been kind enough to support “A Broad Sheet,” so I think it well to tell

you that I have decided to transfer my services to another publication, somewhat

of the same nature, to be called “The Green Sheaf,” and of which I shall be the Editor.

The form of the new publication will be about the size of “Punch,” and will consist

of eight pages of literary matter, hand-coloured drawings, and wood-cuts.

(repr in Kaplan et al, 181)

While both Jack and William contributed to The Green Sheaf, and Elizabeth’s Dun Emer Press advertised in its back pages, Smith separated herself from the Yeats family in order to create her own vision for her little magazine. In title, content, and format, she made The Green Sheaf her own, despite W.B. Yeats’s desire to direct and control the publication and its editor. Writing to Lady Augusta Gregory in December 1902, the poet claimed a proprietary interest in the magazine not borne out by the publication itself:

Pamela Smith is bringing out a Magazine to be called ‘The Hour-Glass’ after my

play. I am to write the preface in order to define the policy which I have got them

to take up. The Magazine is to be consecrated to what I called to their delight, the

Art of Happy Desire. It is to be quite unlike gloomy magazines like the Yellow

Book and the Savoy. People are to draw pictures of places they would have liked

to have lived in and to write stories and poems about a life they would have liked

to have lived. Nothing is to be let in unless it tells of something that seems

beautiful or charming or in some other way desirable. (Yeats Letters, p. 271)

When it appeared, however, The Green Sheaf— “edited, published, and sold by Pamela Colman Smith”—boldly embodied her own conception for the magazine in a self-referential cover design (fig. 3). Loosely gathered up and tied with a red ribbon, the bright green “sheaves” of paper feature a front-facing picture with implied letterpress and, on an inside sheaf, Smith’s idiosyncratic monogram (fig. 3). Described by Katharine Cockin as a “a caduceus with snake-entwined staff formed by the etiolated letter P overlaid with a C and an S,” this monogram adorns her work throughout her career (“Bram Stoker,” 170).

As an arts-and-crafts little magazine, The Green Sheaf respected the materials of its making, valued its collaborative processes of production, and expressed art’s role in envisioning a better world. Informed by Pamela Colman Smith’s feminist principles, which sought to support women in business as well as art, the magazine also had a commercial agenda directed at helping women make an independent living. On the Yellow Nineties magazine rack, only The Venture (1903/1905) shares The Green Sheaf’s particular combination of arts-and-crafts values, commercial interests, and feminism. With its designer’s interest in integrating image, text, and ornament, The Green Sheaf is certainly comparable to other arts-and-crafts little magazines, such as The Dial and The Evergreen, but they eschewed the mainstream market and did not include advertising pages. In contrast, Yellow Nineties little magazines aiming to be aesthetic without being artisanal tended to include the marketplace in their back pages. The Pageant, The Savoy, and The Yellow Book, for instance, used the most up-to-date technological methods available and advertised publishers and businesses aligned with them in their back pages and supplements. Although The Green Sheaf was an arts-and-crafts magazine, Smith also understood that advertisements were a means of networking producers and consumers. Notably, The Green Sheaf’s back pages prominently featured the work of women connected to the little magazine and its editor, including authors, artists, shop owners, publishers, textile designers, and craft instructors. Smith was particularly energetic in promoting her own work, advertising her hand-coloured books and prints, the Green Sheaf Press and its titles, the Green Sheaf School of Hand-Colouring and its services, and her “for hire” performances as Gelukiezanger, teller of Jamaican trickster tales.

The Green Sheaf’s commercial orientation clearly distinguishes it from A Broad Sheet, whose arts-and-crafts approach to magazine-as-art-object it otherwise shares. Smith brought her knowledge of hand colouring with her when she joined Jack Yeats to co-edit A Broad Sheet. It seems likely that Smith developed her hand-colouring method when she built her first toy theatre for Henry Morgan, her play about a seventeenth-century privateer. This dramatic spectacle, which included 300 characters and elaborate scenes, was first staged in Kingston, Jamaica, in 1896 (O’Connor, “Primitivism,” 161). Toy theatres became popular in the early years of the nineteenth century, when consumers could buy printed sheets of figures and sets for “penny plain” or “tuppence coloured.” Smith’s hand-colouring method, as Melinda Boyd Parsons observes, “was undoubtedly related to the stenciling process used for theatrical sheets” (To All Believers, np). Given Smith’s strong interest in pre-industrial folklore and artisanal practices, it makes sense that she should develop a stenciling method for hand-colouring images in her prints, books, and magazines. One of her first hand-coloured prints, an illustration for Yeats’s The Land of Heart’s Desire (1898), was commissioned by R. H. Russell in New York, years before she met the poet and his family (O’Connor, “Primitivism,” 161). In 1899, Smith brought out two editions of folklore with hand-coloured illustrations, The Golden Vanity and The Green Bed and Widdicombe Fair. In a review published in The Lamp in 1903, all three of these works were praised “for the freshness of color and directness of design”—features the critic anticipated would be evident in the forthcoming Green Sheaf (repr in Kaplan et al, 180). Later, a critic in the Academy confirmed that the magazine’s “chiefest charm lies in the hand-coloured prints, which are highly decorative, simple in treatment and of a pleasant old-world flavour” (“Literary Notes” 137). The reviewer’s remarks highlight how aptly The Green Sheaf’s artisanal production methods expressed its subject matter and thematic concerns.

The Prospectus announced that “The First Number will be published on the 30th January, 1903,” with “thirteen numbers in the year” (qtd in Kaplan et al, 181). The print run was indeed completed in thirteen issues, but the first issue came out in spring, rather than winter. The Green Sheaf ran from May 1903 to May 1904; subscriptions went for thirteen shillings, and individual copies could be had for thirteen pence. The unusual yearly number aligns The Green Sheaf with other little magazines, such as The Dial and The Evergreen, that set out to challenge industrial time with an alternative seriality. In addition to the number of issues, the distinctive pricing system suggests that the number thirteen may have been as important to Pamela Colman Smith’s conception of The Green Sheaf as its titular colour. Why this was so is less clear. One possibility may be that Smith wished to follow a lunar calendar. The year falling between May 1903 and May 1904 had thirteen, rather than twelve, full moons; the extra one is commonly known as a “blue moon.” Phases of the moon have traditionally been associated with women, but there may have been an additional appeal to Smith and her circle. In his collection of fairy tales, The Blue Moon (1904), Smith’s fellow feminist Laurence Housman used the symbol to express the naturalness of same-sex love. Although Smith’s sexual orientation, like her ethnic origin, is unknown, her social networks included many in the Victorian queer community, and her artwork often featured androgynous figures.

The significance of the number thirteen may, however, derive from the initiation ceremonies of the Order of the Golden Dawn rather than the lunar year. As an initiate, Smith would have been taught “the appearance, meanings, and methods” of the tarot cards (Kaplan et al, 373). In the tarot deck that Smith was to design for Arthur Waite in 1909, Number 13 is the Death card, indicating “rebirth, creation, destination, renewal” ( Waite 97). Notably, The Green Sheaf was launched in the same year that the Order of the Golden Dawn experienced a schism: members interested in magic and the occult followed W.B. Yeats, while members like Smith, who was more interested in a Judeo-Christian mysticism, stayed with Arthur Waite (Kaplan et al, 352). The split within the Golden Dawn at this time may have strengthened Smith’s determination to produce her Green Sheaf magazine on her own, apart from W.B. Yeats’s directives. Later, when she designed the famous Rider-Waite tarot deck, she used a pictorial style and symbolism akin to her illustrations for The Green Sheaf (see fig. 4). Given Smith’s familiarity with the tarot deck, it seems likely that the combination of the magazine’s titular colour and thirteen-issue seriality aimed to associate The Green Sheaf with both the transformative creation of “fresh young things” and the renewal of “old world” things that are “green forever” (fig. 1). This linking of old and new through a perennial colour was similarly used in the Edinburgh-based Celtic magazine, The Evergreen: A Northern Seasonal. Green is also representative of Ireland itself, and Pamela Colman Smith’s Green Sheaf was at the heart of the Irish Revival, featuring Celtic myth and story as well as many of the key contributors to the movement.

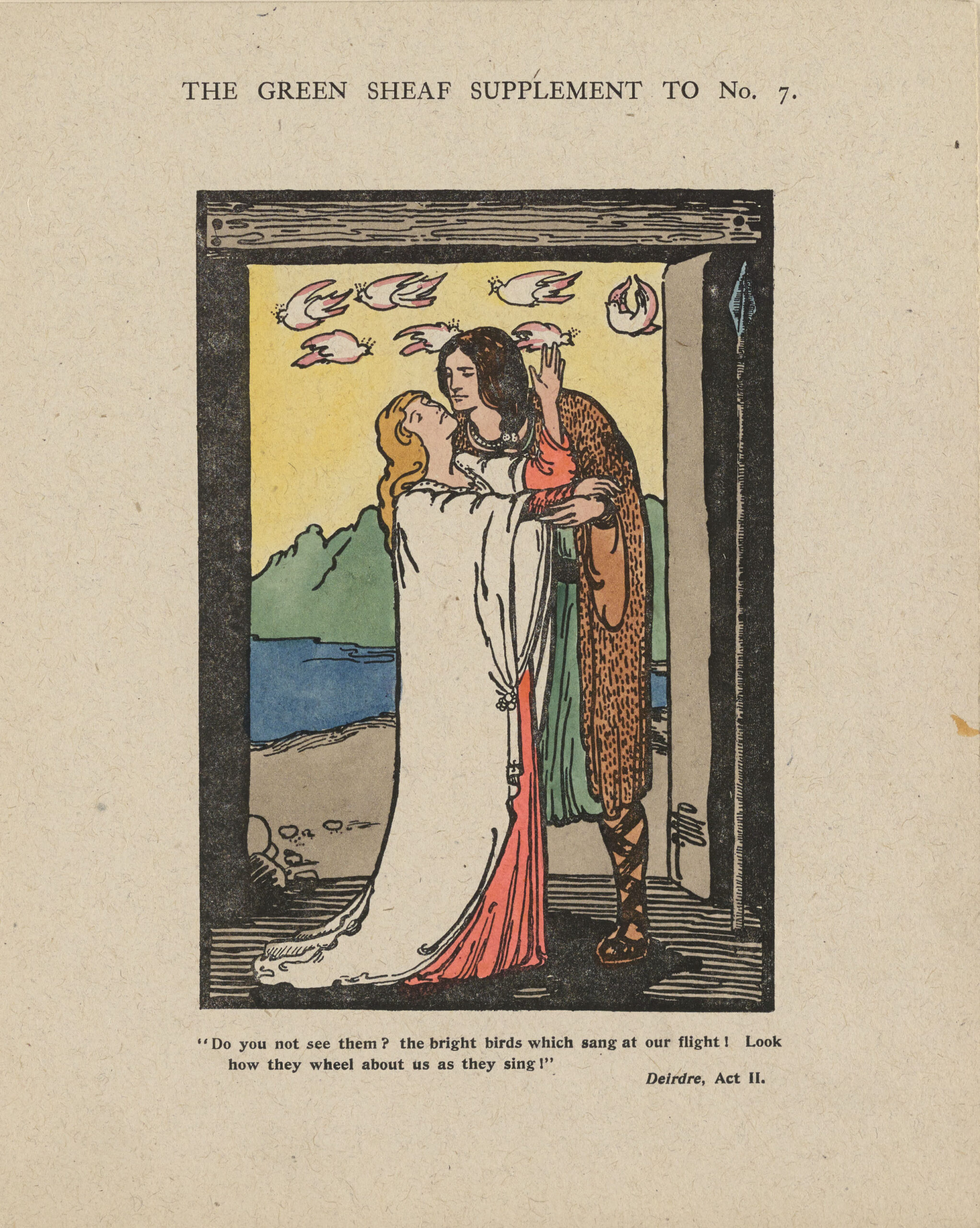

Although it had a limited print run and each issue was of a very modest size, The Green Sheaf included some 50 contributors, with American, British, Dutch, German, Irish, Japanese, and South African nationalities. The Prospectus announced that the new publication “will consist of eight pages,” but in fact almost half of the thirteen issues (6/13) extended to sixteen pages, and some of the shorter numbers were augmented with substantial supplements. The eight pages of Number 7, for example, were enhanced by a twelve-page supplement—truly a case of the paratext overpowering the text. The insert was Deirdre: A Drama in Three Acts, by A.E. (George Russell), one of the leading figures of the Irish Revival. Cecil French and Pamela Colman Smith each provided a hand-coloured illustration (fig. 4). French published in almost every issue of The Green Sheaf, and A.E. was a regular contributor. Other members of the Irish Revival movement who contributed to the Green Sheaf include Lady Alix Egerton, Lady Augusta Gregory, W. T. Horton, J. M. Synge, and the Yeats brothers.

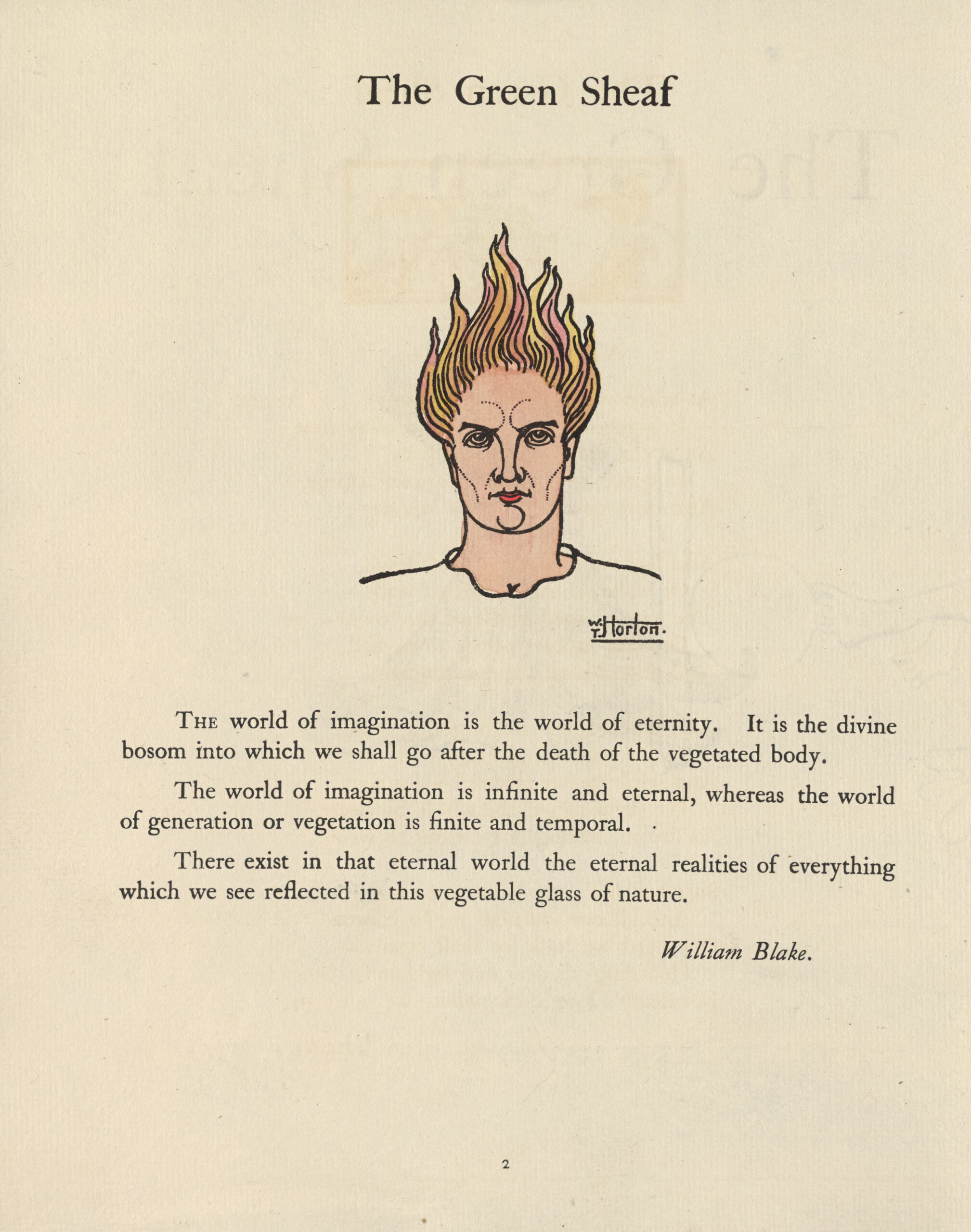

In addition to publishing contemporary artists and authors from her networks of Irish and folklore revival, theatre, and feminist activism, Smith also included some of her most admired predecessors in her magazine. Foremost among these are writer and educationalist Anna Barbauld (1743-1825) and poet, artist, and printer William Blake (1757-1827). Notably, Smith had tried, without success, to interest publishers in illustrated editions of both these writers. It is possible that some of her illustrated excerpts from Barbauld’s Lessons for Children (1778), which appear in Green Sheaf Numbers 4, 9, and 13, were from this project. The two extracts from Blake, in Numbers 2 and 8, were illustrated by W. T. Horton (1864-1919), another member of the Golden Dawn who was attracted to Blake’s ideas about the transient physical world mirroring the eternal infinite (fig. 5). As a thinker, artist, and printer who made and hand-coloured his own books, Blake was a significant inspiration for Smith. His presence in The Green Sheaf acknowledges this debt. Insightful contemporaries also made the connection. Writing in Camera Work after Smith exhibited some of her work at the avant-garde Stieglitz Gallery in New York in 1909, Benjamin de Casseres identified her as a visionary who “approaches Blake and Beardsley” in her art (qtd in Pyne 53).

In the early twentieth century Smith was enmeshed in networks of art, performance, and feminist cultures on both sides of the Atlantic. Her range of influence, moreover, was unusually wide, spreading not only across disciplines and media, but also across artistic groups in London, Dublin, New York, and, to some extent, the continent (O’Connor, “Disgruntled” 73). Despite these transnational connections, however, The Green Sheaf was not widely reviewed and does not seem to have sold enough copies to sustain the cost of its artisanal production. As Smith wrote to Albert Bigelow Paine, an American children’s magazine editor who contributed to The Green Sheaf’s ninth issue, “Green Sheaf does not pay yet—it is most discouraging to go on working on it” (qtd in Kaplan et al, 55). Although she hinted that The Green Sheaf might convert to a semi-annual production after completing its first year, this did not happen. Instead, Smith turned to the businesses she had built up from her publishing venture, the Green Sheaf School of Hand-Colouring and the Green Sheaf Press, both of which she advertised in her magazine. Elizabeth O’Connor speculates that students at the School may have helped hand-colour issues of The Green Sheaf (“Disgruntled” 85). There is no direct evidence of this, \ though the possibility is supported by timing: the School opened in April 1903, just as the first number of The Green Sheaf was being prepared. The two operations—School and Press—were collaborative efforts with Smith’s friend, “Mrs. Fortescue” (possibly Ethel P.F. Fryer-Fortescue, a member of the Golden Dawn whose signature appears in Smith’s Visitor’s Book at this time). Like the magazine, the Green Sheaf Press featured writing by women and works of fantasy and folklore. One of these was Pamela Colman Smith’s own Chim-Chim Stories (1905), a hand-coloured companion to her earlier collection of Jamaican folktales, Annancy Stories, brought out by R. H. Russell in 1899.

In her letter to Paine complaining of The Green Sheaf’s failure to become commercially viable, Smith alluded to the potential success of her performative story-telling: “I am telling Annancy stories very often now and hope in time to make some money by it” (qtd in Kaplan et al, 55). She may have hoped that the Chim-Chim publication could be sold at her performances in the role of Gelukiezanger, the persona she adopted for her oral tellings of Jamaican tales. As she had done with her hand-coloured prints of Ellen Terry, her hand-coloured books of folklore, her School of Hand-Colouring, and her Press, Smith advertised her storytelling services in the back pages of The Green Sheaf (fig. 6).

Despite being an innovative and enterprising entrepreneur, performance artist, and creative producer of books and magazines, however, Pamela Colman Smith was always impecunious. After her death, she and her work fell into obscurity, but recent scholarship has begun to reassess her oeuvre. The Yellow Nineties digital edition of The Green Sheaf allows users to study Smith’s editorial theory and artistic practice in the context of other innovative little magazines produced in late-nineteenth and early twentieth century Great Britain.

©2021 Lorraine Janzen Kooistra, FRSC, Ryerson University, Toronto

Selected Publications by Pamela Colman Smith

- Annancy Stories. R. H. Russell, 1899.

- Chim-Chim Stories. Green Sheaf Press, 1905.

- The Golden Vanity and the Green Bed. Doubleday and McClure, 1899.

- The Green Sheaf, 13 vols., 1903-1904.

- “The Lament of the Lyceum Rat.” Headpiece illustration for Mary Brown, The Green Sheaf, vol. 5, 1903, p. 1903, p. 8.

- The Land of Heart’s Desire, by W.B. Yeats. Triptych print. R. H. Russell, 1898.

- Prospectus to The Green Sheaf, n.d. Reprinted in Kaplan et al, p. 181.

- “A Protest Against Fear.” The Craftsman, vol 11, no. 6, March 1907, p. 728.

- Shakespeare’s Heroines. Calendar for 1899. R. H. Russell, 1899.

- “Should the Art Student Think?” The Craftsman, vol. 14, no. 4, July 1908, pp. 417-19.

- Sir Henry Irving and Miss Ellen Terry, drawn by Pamela Colman Smith. Doubleday & McClure, 1899.

- Widdicombe Fair, Doubleday and McClure, 1899.

Selected Publications About Pamela Colman Smith.

- Armstrong, Regina. “Representative American Women Illustrators: The Decorative Workers.” The Critic, vol. 36, no. 6, June 1900, pp. 52-59.

- Bowe, Nicola Gordon, and Elizabeth Cumming. The Arts and Crafts Movement in Dublin and Edinburgh 1885-1925, Irish Academic Press, 1998.

- Cockin, Katharine. “Bram Stoker, Ellen Terry, Pamela Colman Smith and the Art of Devilry.” Bram Stoker and The Gothic: Formations to Transformations, edited by Catherine Wynne, Palgrave Macmillan, 2016, pp. 159-171.

- —. “Pamela Colman Smith, Anansi, and The Child: From The Green Sheaf (1903) to the Anti-Suffrage Alphabet (1912). Literary and Cultural Alternatives to Modernism, edited by Kostas Boyiopoulos, Anthony Patterson, and Mark Sandy, Routledge 2019, pp. 71-84.

- Kaplan, Stuart R., with Mary K. Greer, Elizabeth Foley O’Connor, and Melinda Boyd Parsons. Pamela Colman Smith: The Untold Story. U.S. Games Systems, 2018.

- “Literary Notes,” The Academy and Literature, vol. 66, no. 1657, February 6, 1904, p. 137.“London Editors Who Are Women.” Review of Reviews, vol. 27, no. 161, May 1903, p. 485.

- O’Connor, Elizabeth. “Pamela Colman Smith’s Performative Primitivism.” Caribbean Irish Connections: Interdisciplinary Perspectives, edited by Alison Donnell, Maria McGarrity, and Evelyn O’Callaghan, University of the West Indies, 2015.

- —. “‘We Disgruntled Devils Don’t Please Anybody’: Pamela Colman Smith, The Green Sheaf, and Female Literary Networks.” South Carolina Review, vol. 48, no. 2, Spring 2016, pp. 72-89.

- Parsons, Melinda Boyd. To All Believers: The Art of Pamela Colman Smith. Catalogue of the Exhibition, Delaware Art Museum, 1975.

- “Pamela Colman Smith.” The Lamp, vol. 26, 1903. Reprinted in Kaplan et al, p. 180.

- Pyne, Kathleen A. Modernism and the Feminine Voice: Georgia O’Keefe and the Women of the Stieglitz Circle, University of California Press, 2007.

- Waite, Arthur Edward. The Pictorial Key to the Tarot. U.S. Games, 2008.

- “Writers and Readers: Illustrated Notes of Authors, Books and the Drama.” The Reader, vol. 2, no. 4, September 1903, pp. 331-32.

- Yeats, William Butler. The Collected Letters of W.B. Yeats, vol. 3 (1901-1904), Electronic Edition, 2002.

MLA citation:

Kooistra, Lorraine Janzen. “’A Paper of Her Own’: Pamela Colman Smith’s The Green Sheaf (1903-1904).” Green Sheaf Digital Edition, Yellow Nineties 2.0, edited by Lorraine Janzen Kooistra, Ryerson University Centre for Digital Humanities, 2023. https://1890s.ca/green-sheaf-general-introduction/.