Tracing the Printed Page Online: Letterpress, Digital Markup and the Process of Remediating The Evergreen for Yellow Nineties 2.0

By Rebecca Martin

In the summer of 2017, I was fortunate enough to be hired as a research assistant at Ryerson’s Centre for Digital Humanities. At the time, the Centre was in the process of digitally remediating Patrick Geddes’s The Evergreen: A Northern Seasonal for Yellow Nineties 2.0. The process of remediation, I was told, involved using the descriptive markup language of the Text Encoding Initiative, or TEI, to encode articles, poems, stories, and other textual components of this fin-de-siècle magazine. While I had very little experience with computer coding of any kind, my experience as a letterpress printer made the process feel strangely familiar—the laborious, finicky and at times meditative quality of encoding reminded me of hand-setting type. While assisting in the process of remediating The Evergreen, I found that TEI encoding required hours of attention to the structure of the printed page. My focus was not only on the content of the words, but also their placement. Like a letterpress compositor, who remediates hand-written manuscripts for the printed page, the TEI encoder works to translate text from one type of page to another to facilitate a broader readership. In the case of TEI markup, this readership includes not only human readers but also computer search engines and aggregators.

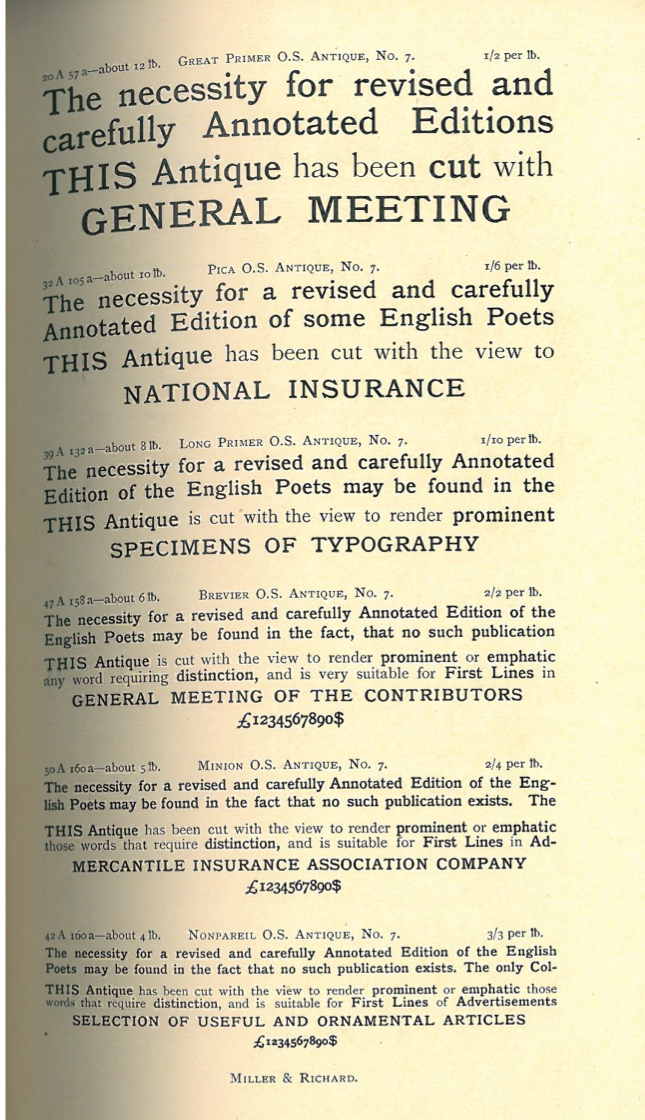

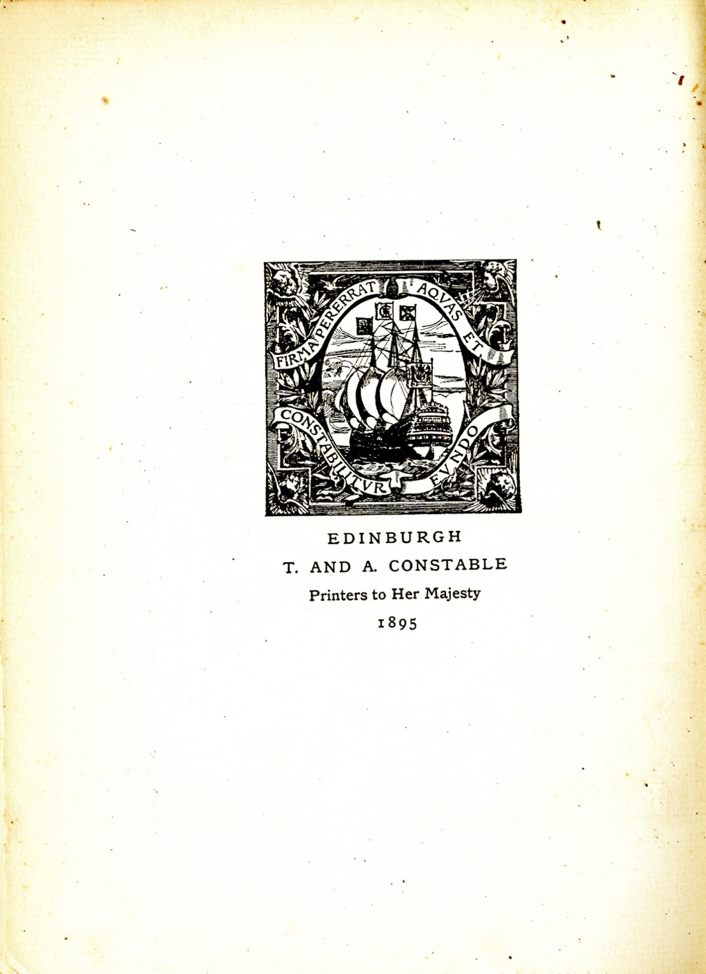

While electronic publications can produce anxiety about the shifting role of print in a digital age, the remediated Evergreen could never stand in for the first printed volumes. Their aesthetic and material qualities were informed by the Arts and Crafts movement and were connected to the political vision of the periodical’s founder, Patrick Geddes (Kooistra 8). The Evergreen was published in the Lawnmarket of Edinburgh by Patrick Geddes & Colleagues and in London by T. Fisher Unwin. In Edinburgh, Geddes chose a local commercial press, T. & A. Constable Ltd., to print the volumes. They are typeset in a dense, black font, called Old Style Antique, purchased from another Edinburgh firm, the type foundry Miller and Richard, rooting The Evergreen materially and philosophically in the city of its origin.

Though print and digital editions are often considered in opposition to one another, the spaces of similarity and divergence between these two mediums can provide insight in to the shifting role of text-based practitioners as well as the metaphors that we use to think about text creation. Compelled by my experience as both a letterpress printer and a TEI encoder, this essay examines the complex relationship between these two practices of remediation. The first section considers the translation from print to the digital page through the writings of two typographers: Beatrice Warde and Robert Bringhurst. The second section provides historical context regarding the publication of the letterpress volumes of The Evergreen in Edinburgh. Finally, this essay turns to the process of digitally remediating The Evergreen at Ryerson’s Centre for Digital Humanities in Toronto, around 120 years and over 5,000 kilometers from the time and place of The Evergreen’s first publication.

I. The Printed and Digital Page

The process of remediating The Evergreen in twenty-first century Toronto involves a translation from the printed page—a surface whose production is rooted in the technological, social, and political circumstances of 1890s Edinburgh—to the digital page, a surface that is multivalent and subject to change over time. The same design principles that have historically been applied to typography in print cannot be perfectly applied to a digital context. In 1932, the scholar and typographer Beatrice Warde famously argued that typography should be akin to a crystal goblet, or clear vessel, that recedes into the background to allow for the unimpeded transfer of meaning from the printed page to the reader (1). Warde’s metaphor for typography takes for granted that the printed page functions as a secure container for meaning, regardless of the quality of its craftsmanship.

It is the stability of letterpress—the structured sequencing of metal type—that facilitates Warde’s metaphor. In the case of an online or digital page, continual upkeep is required on the part of an encoder and editor, or else any number of factors may compromise the page’s legibility. Adding to this, in a digital context, even when functioning perfectly, the appearance of text may vary between screens or devices. An online text is not a single, stable entity but an ongoing transfer of information between encoders, technologies, and readers.

The contemporary typographer Robert Bringhurst has gone so far as to claim that computers inhibit readers’ ability to engage with writing in that technology allows us to be passive consumers of text rather than active participants in its formation and dissemination (3). In The Typographic Mind, Bringhurst argues that “many people now cannot form legible letterforms at all except by tapping on a keyboard. For those people, writing and the alphabet have, quite literally, ceased to be human” (3). For Bringhurst, the typographic output of a master craftsperson facilitates a human connection to the text. The craftsmanship required to achieve this quality, which is bound to centuries of tradition, is not yet achievable on a computer.

Bringhurst’s view suggests that the digital page is a poor substitute for print. It is true that no document can be digitally remediated without loss. There will always be information left behind in the translation from one medium to another. This information is often material rather than textual. While remediation is necessarily an imperfect translation, the spaces of divergence between printed and online pages do not have to be viewed as flaws. In addition to providing multiple avenues of accessibility, searchable digital editions can highlight features of the originals, clarifying connections between volumes, contributors, and pieces, that the print publications may not readily offer. From a practitioner’s perspective, setting type and encoding text also have some significant similarities. Like letterpress printing, marking up a text in XML (Extensible Markup Language) is labour intensive, requiring care and some specialized knowledge. This being the case, coding is not removed from the human hand or attentive mind. While few readers will have the opportunity to typeset their favourite volumes, the XML code used to create the digital edition of The Evergreen is readily available on The Yellow Nineties Online for any reader to observe and even remix or reuse.

II. The Letterpress Evergreen

The four volumes of The Evergreen were imagined by Patrick Geddes & Colleagues as a unification of artistic and scientific thought, a printed expression of Edinburgh’s Celtic Revival movement and Geddes’s own aesthetic and political vision for the city’s revitalization (Kooistra 2). The volumes are richly decorated with illustrations and ornaments that reflect this vision. Elisa Grilli has pointed out that “the detailed layout, numerous artworks, ornaments, woodcuts, and paper quality all show that much attention went into making what was ultimately both an experimental and sumptuous medium” (31). Each volume of The Evergreen was printed on high-quality paper, bound in embossed leather, and contained no advertisements. The typesetting appears to have been carefully considered. Deliberately wide margins, ornamental dropped capital letters, and lines of type that taper towards the centre at the end of textual pieces all contribute to a periodical in which visual and verbal components are interconnected. Grilli writes that, “The association of art and writing created a harmonious balance between textual and visual material. Indeed, the tables of contents blend literature, art, criticism, and ‘life’ throughout the periodical, each issue resonant with a particular season” (26). While the volumes’ material and aesthetic qualities were priorities for Patrick Geddes & Colleagues, Grilli’s archival investigations reveal that the editors debated how best to balance quality with affordability to facilitate circulation (33). As Lillian H. Rea asks in the minutes of an early editorial meeting, “Do we not want to avoid the pit into which Morris fell with his books?” (Grilli 33). Here, Rea is cautioning against creating print volumes that are finely crafted but inaccessible to a broader public, such as those created by William Morris in London. Despite the fact that the volumes of The Evergreen were somewhat expensive to purchase, it appears that Patrick Geddes & Colleagues were more concerned with disseminating their ideas for a revitalized Edinburgh than creating profitable works (Grilli 33).

The Evergreen was printed in four volumes by the firm T. & A. Constable Ltd. in Edinburgh between 1895 and 1896/97. T. & A. Constable was unique among commercial printers in its attention to both craftsmanship and commercial production. According to Duncan Glen, the firm was one of only two in Edinburgh whose output exhibited a high standard of craftsmanship while also prioritizing affordability and readability (124). Operating in the city’s Old Town since 1833, T. & A. Constable was connected to Edinburgh’s burgeoning Arts and Crafts movement through W. B. Blaikie, who owned the firm alongside Archibald Constable at the time of The Evergreen’s publication. Glen writes that, “It was W.B. Blaikie (1848-1928) who, as chairman of the company, established T. & A. Constable as exceptional book printers” (125). Blaikie—who was a cousin of the writer Robert Louis Stevenson—was highly involved in the Edinburgh arts community. Among other engagements, he was a member of the Edinburgh Social Union, founded by Patrick Geddes and his wife Anna Morton, and held night classes for employees of T. & A. Constable (Addison 151). During his time at the Edinburgh Social Union, he mediated between the Union’s artists and book designers and “binders at Constable’s, such as Jane Easton, to produce books exhibited by Karslake for the Guild of Women Binders and the Arts and Crafts Exhibition Society in 1898” (Addison 154). By drawing upon the principles of Edinburgh’s Arts and Crafts movement, Blaikie helped to situate T. & A. Constable as not only a successful commercial press but also a press of literary and artistic merit.

The success of T. & A. Constable was owed in part to the quality of fonts acquired from another Edinburgh based firm, the type foundry Miller and Richard. A well-regarded firm who sold their fonts in local and international markets (Glen 125), Miller and Richard innovated several new fonts, including the Old Style Antique font used to print The Evergreen. Old Style fonts were a popular alternative to the “didone” or “modern” style of fonts that dominated European typography for most of the nineteenth century (Ovnik 18). Modern style typefaces were austere and classical, with a strong contrast between thick and thin lines. Derived from fonts developed by Firmin Didot in France and Giambattista Bodini in Italy in the eighteenth century, these fonts owed their popularity, in part, to their mathematical regularity and the associated qualities of reason (Lawson 244; Ovnik 18). G. W. Ovnik writes that for nineteenth-century typesetters, “the didone principle seemed inexorably logical. It therefore drove its adherents to the final consequences of clear distinction between thick and thin lines; of symmetry and consistency (i.e. equality) in the treatment of similar elements” (18). Unfortunately, modern style fonts were often ill-suited to mass production, and many commercial book printers did not take care in adjusting their printing techniques to suit the fonts that they were using, resulting in “dull grey pages that, aesthetics apart, impaired readability” (Williams 101).

Old Style fonts updated an eighteenth-century font called Caslon. Caslon had largely fallen out of use in the nineteenth century, until 1844 when Chiswick Press published an edition of The Diary of Lady Willoughby that was typeset in an original Caslon font, thus spurring renewed interest (Morris 27). Between 1852 and 1860, Miller and Richard commissioned the punch cutter Alexander Phemister to create a revised version of the font that adjusted it to appeal to Victorian tastes (Ovnik 26). This modernized version of Caslon built on the font’s popularity but modified the design to give it “better wearing and printing properties” (Morris 28). As Stanley Morison writes in A Tally of Types, “What in Caslon did not conform to Victorian ideas of typographical rectitude had been cast out…Eyes used to sharpness of cut and regularity of letter-width found both in Old Style” (16). In 1890, the English writer Talbot Baines Reed commented that “this opportune return to the past, I venture to think, is a hopeful sign for the future” (Morison 16). In this instance, Reed could have easily been alluding the philosophy underpinning The Evergreen. Miller and Richard’s Old Style was widely copied and became so popular that it became known as a generic font used for printing books of historical, literary, or artistic significance, and in books where increased legibility was essential (Ovnik 21).

The Evergreen was not set in Old Style, but in a denser variation of the font called Old Style Antique. “Antique” refers to the font’s bold face and slab, or block-like, serifs (Ovnik 27). Old Style Antique was developed in response to a design issue that arose surrounding Old Style. While nineteenth-century printers often combined different fonts in the same body of text to add emphasis, the distinctive nature of Old Style made it difficult to mix with other fonts, creating the need for a thicker version (Ovnik 27). According to Ovnik, two distinct bold versions of Old Style, both called Old Style Antique, emerged simultaneously in the late 1860s—one in Philadelphia and one in Edinburgh (27). Miller and Richard produced the Edinburgh version of the font around 1869 in Brevier (size 8), Long Primer (size 10), Pica (size 12), and Great Primer (size 18). A 1902 Miller and Richard specimen book from the St. Bride’s Print Library in London indicates that the body of The Evergreen was typeset in a version of Old Style Antique called “Long Primer O. S. Antique No. 7.”

The technology that was used to print and bind the original volumes of rend=”italic”>The Evergreen, including the letterpress machines used by T. & A. Constable and the fonts that they purchased from Miller and Richard, influenced the magazine’s aesthetic qualities. While The Evergreen was published at a time of rapid modernization for print technology, records indicate that T. & A. Constable employed compositors as late as 1911 (Glen 125), making it likely that the volumes were typeset manually. As David Finkelstein and Alistair McCleery have noted in Edinburgh History of the Book in Scotland, Volume 4,

One of the less desirable inheritances from nineteenth century mechanization and growth was too many books that were badly designed, using poor type, and badly printed on cheap, perishable paper. The constant renewal of the material book by artists from Morris, the followers of Patrick Geddes, to Hamilton Finlay also reinvigorates, and establishes a quality benchmark for books intended for a more general readership (94).

T. & A. Constable were among the few commercial printers who attempted to meet this benchmark of quality. One revealing decision made by the firm was to use a colophon in the final pages of each volume of The Evergreen. While colophons had widely fallen out of use in Great Britain after the sixteenth century, they were revived by Chiswick Press in London and became widely used among private presses of the day (Glen 124). T. & A. Constable’s colophon depicts a ship ornately framed by four banners that read Firma Pererrat Aquas Et Constabilitur Eundo. Translating roughly to “something firm wanders through water and is made stable by moving,” the paradox asserted by this motto is likely intended to be “a play on ‘stable’ and ‘firm’ with respect to Constable’s name and company, while also possibly alluding to the idea of moveable type making texts stable” (printer’s colophon). That a commercial press such as T. & A. Constable would imprint their volumes with a colophon suggests that the firm aspired to a higher standard of craftsmanship, in the manner of a private press. As a brief self-published history of T. & A. Constable printed in 1937 notes,

The care which was taken over every detail of production, particularly in the preparation of the title pages, sought comparison with the work being done at the same time in England by William Morris. The latter, in the choice of his types and the design of his page, aimed at producing a beautiful book, of which the essential was the appearance, while the first consideration of the books issued from Thistle Street was legibility, bearing in mind the fitness for their purpose (T. & A. Constable Ltd. 11).

Private presses such as Morris’s Kelmscott Press and the Doves Press of T.J. Cobden-Sanderson and Emery Walker are credited with the revival of fine printing in Europe, though Glen argues that “the high quality of work produced by commercial printers in Edinburgh is culturally more important than the very expensive books produced by Morris and his followers” (124). T. & A. Constable cemented its reputation as a press that was both successful and influential by adhering to the commercial values of readability and availability while observing the standard of craftsmanship upheld by private presses.

III. The Remediated Evergreen

Moveable type remediates writing, just as XML markup remediates print. While attention to craft is indicated by T. & A. Constable’s use of the colophon, the firm’s motto, “something firm wanders through water and is made stable by moving,” signals an awareness of the stabilizing nature of print technology. For a printer who is compositing type, the page is created from a series of tiny fragments, which are pieced together to form a whole. As Walter Ong writes,

alphabet letterpress printing, in which each letter was cast on a separate piece of metal, or type, marked a psychological breakthrough of the first order… print situates words in space more relentlessly than writing ever did. Writing moves words from the sound world to the world of visual space, but print locks words into position in this space. (quoted in Lupton 91)

To remediate a printed volume for an online environment implies a translation from the solidity of print to the multivalence of the virtual page, where a variety of factors can change the overall look and readability of text. The quality of stability inherent to print that facilitates Warde’s metaphor of the crystal goblet cannot be applied to a digital context. The online page functions more like a garden that requires continual upkeep than a crystal goblet or secure container of any kind; without maintenance, any number of variables might compromise an online page’s readability, including broken links, obsolete code, issues with the server, and more. A digital page is not a single surface but multiple layers of code that are interconnected. While changes in print technology could not possibly impact the look of print volumes that have already been produced, this is not the case online, where updated technology can alter the readability of pages that already exist. When publishing online, a practitioner’s role must continue for as long as a website is live.

The process of remediating The Evergreen for a digital edition first involves scanning each volume’s pages using optical character recognition (OCR) software. While this technology accurately captures most letterpress, a coder must inspect each line to confirm accuracy, revise any errors made by the OCR process, format the text, and add metadata information using XML. Short for “extensible markup language,” XML is a descriptive language that allows a coder to mark-up a text through user-defined tags. These tags can be read by humans, but their larger function is to define the document for computer readability. In encoding The Evergreen, the Yellow Nineties 2.0 editorial team has adhered to the set of tags defined by the Text Encoding Initiative (TEI)—the standard format most widely used in humanities scholarship. The XML language of the TEI allows coders to define aspects of a text such as paragraphs, line-breaks, headings, titles, stanzas, and more. In addition to formatting the page for readability, XML can also be used to embed other searchable information in a text, such as publication information, a standard editorial statement, and descriptions of images, or image proforma, that make visual elements searchable while also providing descriptions for those who require the use of a screen-reader. After XML coding has been completed, the marked-up item is transformed into HTML for digital display. On the Yellow Nineties 2.0 interface, users have a number of ways to engage the contents of The Evergreen. They can go directly to a specific work via the hyperlinked Table of Contents, open a continuous HTML file of a volume’s texts and images, or select the flipbook view that allows them to see scans of the original printed pages in simulated codex format. Users can also download pdf files of texts and jpgs of images. If interested, users can choose to look at the XML code that was used to create the HTML page, and even copy and re-use that code for their own purposes. Operating in the background of the edition, the code ensures interoperability, transferability, and searchability.

The practitioner’s work of coding provides a contemporary parallel to hand-compositing, in that both tasks are painstaking, time-consuming, and have the same aim of facilitating a broader readership. The word “markup” itself is rooted in a printing term. As noted in the TEI’s “Gentle Introduction to XML,” “Historically, the word markup has been used to describe annotation or other marks within a text intended to instruct a compositor or typist how a particular passage should be printed or laid out.” Just as these notes signal layout to a compositor, XML code annotates text through the placement of user-defined tags. The editorial decisions made in marking-up the text for online publication balance readability and intuitive design with fidelity to the original volumes. For instance, while many websites feature responsive design that adjusts line breaks to suit the browser and device being used, we have preserved The Evergreen’s original line breaks and spacing wherever possible. We have also used XML mark-up to embed descriptions of images that appear in the volumes and other editorial information that does not appear on the surface of the page. Just as the fin-de-siècle editors of the printed Evergreen sought to balance the aesthetic appeal of the volumes with an eye to broad availability, we have had to weigh the possibilities of contemporary digital reproduction against fidelity to the original volumes.

Digital remediation offers both a challenge and an opportunity. The original volumes of The Evergreen—which were printed on high-quality paper and carefully typeset with multiple illustrations and embossed covers—were a material expression of Patrick Geddes & Colleagues’ complex vision for cultural renewal in 1890s Edinburgh. The aesthetic qualities of the first volumes of The Evergreen were influenced by the technologies available at the time, including the Old Style Antique font used by T. & A. Constable. This font was itself a product of its time, created in response to a variety of interconnected factors, including the influence of the Arts and Crafts movement across Europe. While digital editions cannot replicate or replace the medium-specific qualities of print, remediation can draw upon the strengths of online publication to attract attention to print editions and create opportunities for scholarship and wider avenues of accessibility and engagement. In marking up the texts of The Evergreen so that they are viewable on the Yellow Nineties 2.0, we have tried to maintain consistency with the original volumes, with the understanding that these digital volumes are a tracing—and not a replication—of the original printed pages, adapted for online readership.

Works Cited

- Addison, Rosemary. “Design and Illustration.” Edinburgh History of the Book in Scotland, Volume 4: Professionalism and Diversity 1880-2000, edited by David Finkelstein and Alistair McCleery, Edinburgh University Press, 2007, pp. 148-154.

- Bringhurst, Robert. The Typographic Mind. Gaspereau Press, 2006.

- Glen, Duncan. “Typography.” Edinburgh History of the Book in Scotland, Volume 4: Professionalism and Diversity 1880-2000, edited by David Finkelstein and Alistair McCleery, Edinburgh University Press, 2007, pp. 122–132.

- Grilli, Elisa. “Funding, Publishing, and the Making of Culture: The Case of The Evergreen.” Journal of European Periodical Studies vol. 1, no.2, Winter 2016, pp. 19-44. http://ojs.ugent.be/jeps/article/view/2638

- Hewitt, Regina. “PATRICK GEDDES (1854-1932),” Yellow Nineties 2.0, edited by Dennis Denisoff and Lorraine Janzen Kooistra, Ryerson University Centre for Digital Humanities, 2016, https://1890s.ca/geddes_bio.html

- Kooistra, Lorraine Janzen. “General Introduction to The Evergreen: A Northern Seasonal (1895 1896/97),” Yellow Nineties 2.0, edited by Lorraine Janzen Kooistra, Ryerson University Centre for Digital Humanities, 2018. https://1890s.ca/the-evergreen-general-introduction/

- Lawson, Alexander. The Anatomy of a Typeface, David R. Goodine, 1990.

- Lupton, Ellen. Thinking with Type: A Critical Guide for Designers, Writers, Editors & Students, Princeton Architecture Press, 2004.

- Miller and Richard. Specimens of modern, old style and ornamental type cast on point bodies. Miller and Richard, 1902.

- Morris, John. “Typefounding.” Edinburgh History of the Book in Scotland, Volume 3: Ambition and Industry 1800-1880, edited by Bill Bell, Edinburgh University Press, 2007, pp. 26-30.

- Morrison, Stanley. The Tally of Types. Cambridge University Press, 1973.

- Ovnik, G. W. “Nineteenth Century reactions against the diode type model – I,” Quaerendo vol. 1, no. 2, 1971, pp. 18-31

- “printer’s colophon,” The Database of Ornament, accessed May 15, 2018, http://ornament.library.ryerson.ca/items/show/29.

- Text Encoding Initiative. “A Gentle Introduction to XML – TEI P5: Guidelines for Electronic Text Encoding and Interchange.” Web. 20 May 2018. www.tei-c.org/release/doc/tei-p5-doc/en/html/SF.html

- T. & A. Constable Ltd. Brief Notes on the Origins of T. & A. Constable Ltd., T. & A. Constable Ltd, 1936, www.scottishprintarchive.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/04/T-A-Constable1.pdf

- Warde, Beatrice. “The Crystal Goblet or Printing Should be Invisible,” The Crystal Goblet; Sixteen Essays on Typography. World Pub. Co., 1956.

- Williams, Helen. “Mechanical Typesetting.” Edinburgh History of the Book in Scotland, Volume 4: Professionalism and Diversity 1880-2000, edited by David Finkelstein and Alistair McCleery, Edinburgh University Press, 2007, pp. 122–132.

MLA citation:

Martin, Rebecca. “Tracing the Printed Page Online: Letterpress, Digital Markup and the Process of Remediating The Evergreen for Yellow Nineties 2.0, ” Yellow Nineties 2.0, edited by Lorraine Janzen Kooistra, Ryerson University Centre for Digital Humanities, 2019, https://1890s.ca/essay_martin_evergreen_tracing/