CRITICAL INTRODUCTION

TO VOLUME 5 OF THE DIAL (1897)

In December 1897, Charles Ricketts and Charles Shannon brought out the fifth and final number of The Dial: An Occasional Publication. Like the previous issue of the preceding year, the last Dial was published by the Vale Press and printed at Ballantyne’s under Ricketts’s supervision, in a run of 270 copies priced at 12 shillings 6 pence apiece. Reverting to a layout not used since the second volume, the contents page was located at the back, rather than the front, of the magazine. Although the number of contents was roughly the same as in earlier issues—ten images, eight pieces of literature, and four decorative initials—the prose and poetry tended to be shorter, so the folio only came to 28 pages, rather than the usual 36. Consistent with Ricketts’s page design in each of the five volumes, only the prose pieces in the magazine were decorated: the interlaced white initials, some with flowers and stems, were printed on a black ground (fig. 1; see also Database of Ornament). The capital “I” was used twice, but inverted the second time, giving it a slightly different appearance. Ricketts embellished the knotwork and strapwork around this letter with the violet and viola, a floral device that Ricketts was proud to have introduced with his Vale Press (Ricketts, Defense 109).

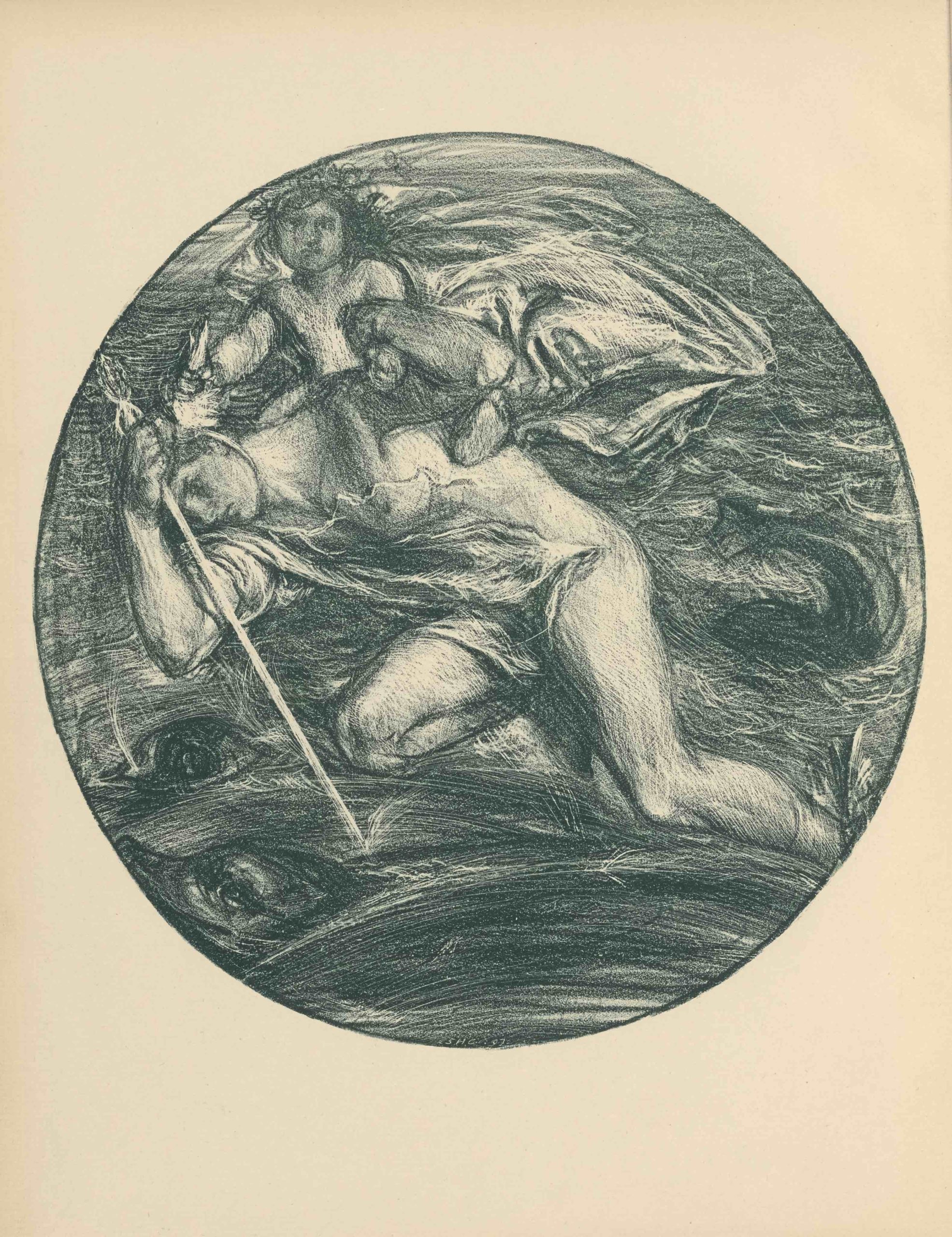

The frontispiece, Charles Shannon’s “The Infancy of Bacchus,” effectively introduces a volume replete with symbolist and neo-pagan concerns (fig. 2). Set within a roundel, the image celebrates masculine creativity and pagan power, with the garlanded baby Bacchus (also known as Dionysus, a nature god of vegetation) carried on the shoulders of Mercury over a sea of sportive dolphins. Shannon’s original lithograph was, according to the Spectator critic, “the best thing” in the volume: “The breadth and largeness of the composition are decidedly impressive” (“Book Review”). Shannon’s other original lithograph, “The Dressing Room” from his Stone Bath series, depicts two nude females in profile in front of a bathtub. Both were printed by the professional lithographer Thomas Way, rather than by the artist himself. As Ricketts put it, “a lithograph may be put out of tune by careless printing, or spoilt outright; temperature and the unaccountable affect it.” The co-editors were glad to use the reliable services of a man whose “dexterous printing and interest in lithography have done…much to popularize the medium” (“Prefatory Note” 149).

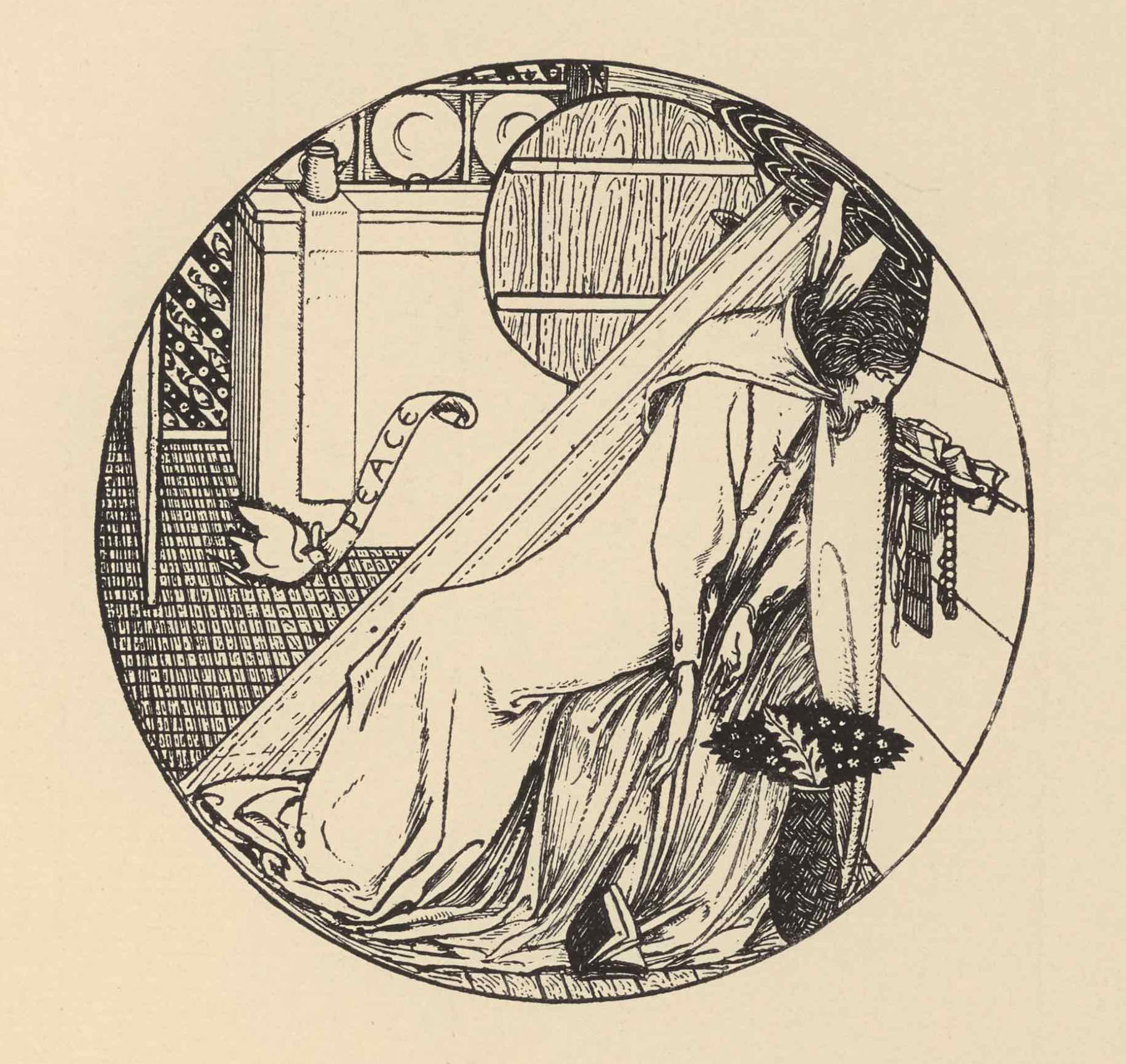

The round frame introduced by “The Infancy of Bacchus” appears twice more in the volume: first, in Shannon’s original woodcut, “December,” and later in Ricketts’s pen drawing, “The Vision of King James the First of Scotland,” reproduced by Carl Hentschel’s state-of-the-art engraving firm (fig. 3). Like the “Illustration to the King’s Quair” published in volume 4 of the Dial (1896), this drawing was prepared for a proposed edition that did not transpire. Ricketts’s biographer, J.G.P. Delaney rightly observes that these illustrations “are in his best Art Nouveau style and have that marvelous sense of design and decorative effect at which he excelled” (98). In the “Vision” illustration Ricketts uses the round frame of the image for decorative and emotional effect, repeating the shape in the ship’s porthole, through which angelic hands and radiant light reach down to the entranced King.

In a Magazine of Art article that year, Gleeson White— Shannon’s co-editor of the Pageant (1896-97)—wrote with insight about Ricketts’s approach to composition and anatomy: “Emotion, passion, and the decorative pattern of his design sway him most; and to that end he evolves types of humanity which are not common, and proportions which do not agree with the record of the Kodak” (307). Like William Morris, Ricketts was more interested in design than in realism: the style of the image should accord with the typography to ensure harmony on the printed page. Just as the modern illustrator treats the represented body from the perspective of design rather than anatomical correctness, Ricketts averred, the modern typographer should display a “logic in the anatomy of [letter] forms”: in both cases, beauty and harmony guide the design (Ricketts and Pissarro 79).

While Ricketts may not have been interested in “the record of the Kodak” as a form of realist art, he was not averse to using photographic processes for reproducing his own pen drawings. His other pen-and-ink illustration in the volume was reproduced by the Swan Electric Engraving Company. “Pan Hailing Psyche Across the River” joins Thomas Sturge Moore’s original woodcut, “Pan Island,” in expressing the fifth number’s pagan and mythic interests. Celebrating the nature god as he had done earlier in “Pan Mountain” (published in the third Dial), Moore depicts a monumental Pan playing his panpipes while clouds roil behind him and vegetation and sheep swirl at his feet.

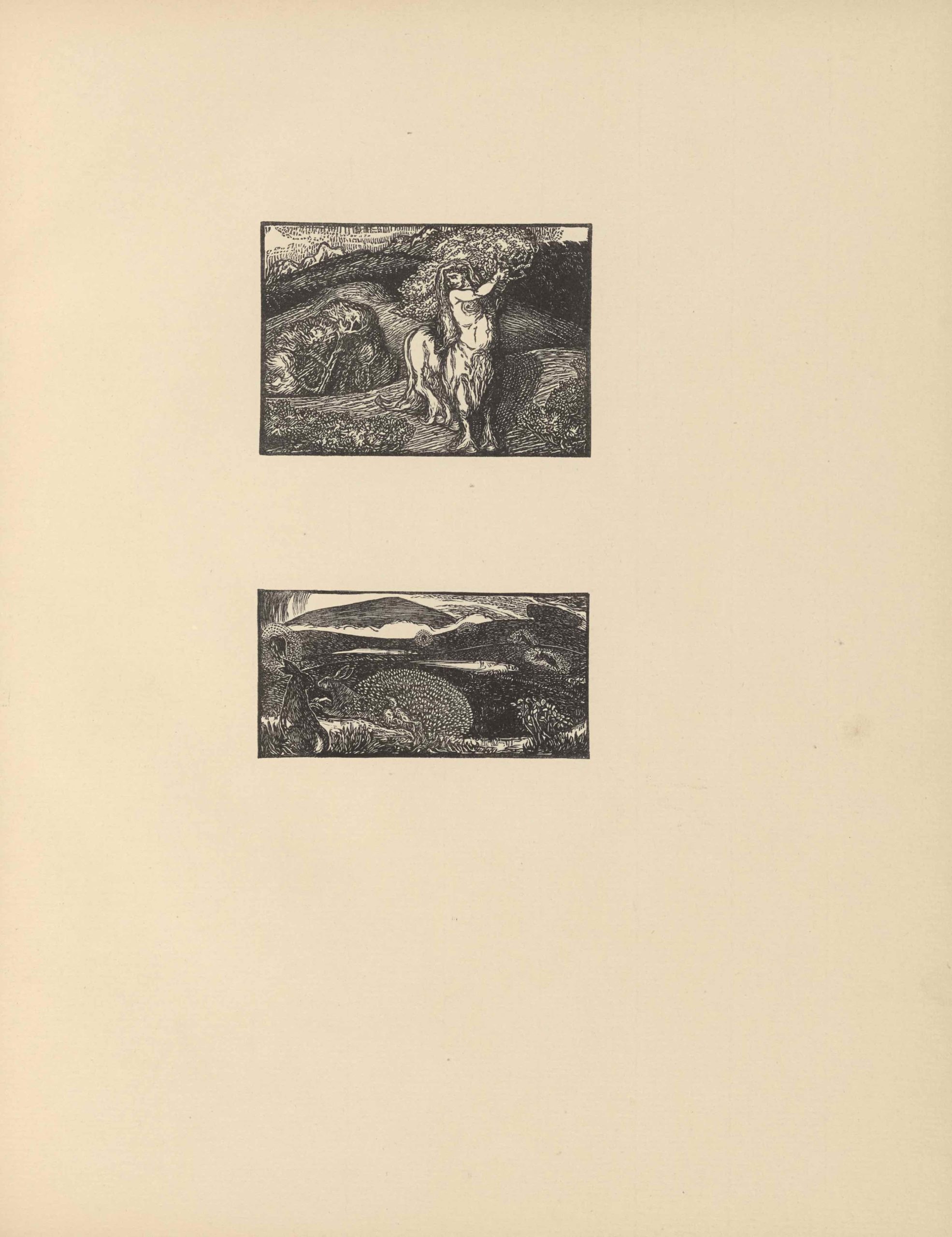

Moore’s two other woodcuts, “Centaur with a Bough” and “The Hare Making Circles in her Mirth,” are printed together on the same page (fig. 4), a method also used for Pissarro’s two woodcuts on the biblical story of Ruth and Naomi, which are situated before the contents page at the end of the volume. Notably, Moore’s images are inserted in the middle of the fanciful story they illustrate: “The Centaur,” by French Romantic poet Maurice de Guerin and translated by Moore.

In his work, De Guerin represented the centaur as “an essential element in nature” (Woodring 8), and this representation appealed to Ricketts’s circle. The coterie of Vale authors and artists were fascinated by centaurs and the pagan, elemental world they evoked. Ricketts had published an appreciative essay on de Guerin in the second volume of The Dial (Unsigned), ornamented with an elaborate centaur headpiece (see Database of Ornament); in the third volume, he engraved a drawing of centaurs by Reginald Savage as the frontispiece. Two years after publishing Moore’s translation of de Guerin’s The Centaur in the Dial, Ricketts’s Vale Press brought out an edition illustrated with Moore’s wood-engravings. Moore, meanwhile, had also published a sonnet on the subject, “Pallas and the Centaur: After a Picture by Botticelli” in the first volume of The Pageant. He later dedicated his long dialogue poem The Centaur’s Booty (1903) to Ricketts, whose admiration of centaurs was equal to his own. In works by Ricketts and Moore, as Carl Woodring observes, the centaur appears as an admirable hybrid creature: “animal, spiritual, and of such divinity as earth affords” (11).

The Symbolist connection is highlighted in the volume’s leading piece of literature, “La Vie Élargie,” a poem in French about the extended, or enlarged life, by Emile Verhaeren. A Belgian poet and art critic, Verhaeren was one of the founders of the school of Symbolism introduced to a British audience in the pages of little magazines such as the Dial, The Evergreen, and The Pageant. By the time of the fifth Dial, however, Verhaeren had moved away from the Symbolism to a socialist position; this makes his poem on the enlarged life a particularly interesting choice for the last Dial. It is also worth noting that, although John Gray regularly contributed materials inspired by, or translations of, works by French Symbolists, for the final number, the poet offered his own approach to mythic symbolism, with the two-part narrative poem, “Leda,” and a fanciful sonnet about “St. Ives, Cornwall.” Moore’s “Phantom Sea-Birds,” a long narrative poem based on the Illiad, also draws on myths of the sea and transformation. Michael Field, who had first published in the Dial in the fourth issue, contributed a short first-person narrative, “The Fate of the Crossways,” in which the speaker describes meeting Hecate, the mythic figure associated with witchcraft and neopaganism. Laurence Housman’s “Open the Door, Posy!” engages more humorously with the supernatural. His tale relates how an impoverished mother and daughter manage to outwit Death the Taxman, Death the Undertaker, and Death the Sexton.

The only essay in the volume is an appreciative piece on the Japanese woodblock artist “Outamaro” (Kitagawa Utamaro, 1753-1806), by Charles Sturt, aka Charles Ricketts. His thesis is that, in contrast to its influence on France, Japanese art has not had a lasting impact on England. His reference to Edmund de Goncourt’s monograph on Outamaro sends the reader back to John Gray’s essay on “Les Goncourts” in the first Dial (1889), which praises the Goncourt brothers for championing the art of Japan and teaching artists to see “the great value of blank space” (12). Sturt/Ricketts compares Outamaro’s eighteenth-century Japanese art with late-Renaissance Italian art and praises him as “an early master of the modern school of art,” thereby offering an alternative art history to that of the western tradition (26).

Although the fifth Dial gave no indication that it was to be the last “Occasional Publication” of this little magazine, a Vale Press prospectus brought out in the new year provided the rationale for its demise: original art and experimental literature now had more ways of reaching an audience. When the Dial was first conceived and produced in 1889, it had been “produced when it seemed impossible to launch original work in any other way,” Ricketts explained. “This is no longer the case, and the series ceases with the necessity for it” (qtd in Delaney 113). With the steady increase in the number of little magazines publishing original art and new literature, Ricketts and Shannon felt justified in bringing the Dial to an end. For the next seven years, Ricketts would put all his energy into the making of beautiful books at the Vale Press, an innovative fine press that was the direct result of design experiments in his little magazine, the Dial (1889-1897).

©2020 Lorraine Janzen Kooistra, FRSC, Professor of English, Ryerson University

Works Cited

- “Book Review.” Rev. of The Dial, vol. 5, The Spectator, vol. 80, no. 3628, 8 January 1898, p. 57. Yellow Nineties 2.0, edited by Lorraine Janzen Kooistra, Ryerson University Centre for Digital Humanities, 2020. https://www.1890s.ca/dial5-review-the-spectator-jan-1898/

- Delaney, J.G.P. Charles Ricketts: A Biography. Clarendon Press, 1990.

- Field, Michael. “The Fate of the Crossways.” The Dial, vol. 5, 1897, p. 11. The Dial Digital Edition, edited by Lorraine Janzen Kooistra, Yellow Nineties 2.0, Ryerson University Centre for Digital Humanities, 2020. https://beta.1890s.ca/dialv5-field-fate/

- Gray, John. “Leda.” The Dial, vol. 5, 1897, pp. 13-15. The Dial Digital Edition, edited by Lorraine Janzen Kooistra, Yellow Nineties 2.0, Ryerson University Centre for Digital Humanities, 2020. https://beta.1890s.ca/dialv5-gray-leda/

- —. “Les Goncourts.” The Dial, vol. 1, 1889, pp. 9-13. Dial Digital Edition, edited by Lorraine Janzen Kooistra, 2018-2020. Yellow Nineties 2.0, Ryerson University Centre for Digital Humanities, 2019. https://1890s.ca/dialv1-gray-goncourt/

- —. “Saint Ives, Cornwall.” The Dial, vol. 5, 1897, p. 12. The Dial Digital Edition, edited by Lorraine Janzen Kooistra, Yellow Nineties 2.0, Ryerson University Centre for Digital Humanities, 2020. https://beta.1890s.ca/dialv5-gray-cornwall/

- Guerin, Maurice de. “The Centaur.” Translated by T. Sturge Moore. The Dial, vol. 5, 1897, pp. 16-21. The Dial Digital Edition, edited by Lorraine Janzen Kooistra, Yellow Nineties 2.0, Ryerson University Centre for Digital Humanities, 2020. https://beta.1890s.ca/dialv5-moore-centaur/

- Housman, Laurence. “Open the Door, Posy!” The Dial, vol. 5, 1897, pp. 4-7. The Dial Digital Edition, edited by Lorraine Janzen Kooistra, Yellow Nineties 2.0, Ryerson University Centre for Digital Humanities, 2020. https://beta.1890s.ca/dialv5-housman-posy/

- Moore, T. Sturge. The Centaur’s Booty. Duckworth, 1903.

- —. “Centaur with a Bough” and “The Hare Making Circles in her Mirth.” The Dial, vol. 5, 1897, np. The Dial Digital Edition, edited by Lorraine Janzen Kooistra, Yellow Nineties 2.0, Ryerson University Centre for Digital Humanities, 2020. https://beta.1890s.ca/dialv5-moore-centaur-hare-AD/

- —. “Pallas and the Centaur: After a Picture by Botticelli.” The Pageant, vol. 1, 1896, p. 229. Pageant Digital Edition, edited by Fred King and Lorraine Janzen Kooistra, Yellow Nineties 2.0, Ryerson University Centre for Digital Humanities, 2020. https://beta.1890s.ca/pageant_volumes/

- —. “Pan Island.” The Dial, vol. 5, 1897, np. The Dial Digital Edition, edited by Lorraine Janzen Kooistra, Yellow Nineties 2.0, Ryerson University Centre for Digital Humanities, 2020. https://beta.1890s.ca/dialv5-moore-pan-ac/

- —. “Pan Mountain.” The Dial, vol. 3, 1893, np. The Dial Digital Edition, edited by Lorraine Janzen Kooistra, Yellow Nineties 2.0, Ryerson University Centre for Digital Humanities, 2020. https://beta.1890s.ca/dialv3-moore-mountian-AD/

- —. “Phantom Sea-birds.” The Dial, vol. 5, 1897, pp. 8-10. The Dial Digital Edition, edited by Lorraine Janzen Kooistra, Yellow Nineties 2.0, Ryerson University Centre for Digital Humanities, 2020. https://beta.1890s.ca/dialv5-moore-phantom/

- Pizzarro, Lucian [sic. Aka Pissarro, Lucien]. “Ruth, Oprah, and Naomi” and “Ruth the Gleaner.” The Dial, vol. 5, 1897, np. The Dial Digital Edition, edited by Lorraine Janzen Kooistra, Yellow Nineties 2.0, Ryerson University Centre for Digital Humanities, 2020. https://beta.1890s.ca/dialv5-pizzarro-ruth-ag/

- Ricketts, Charles, and Lucien Pissarro. “Of Typography and The Harmony of the Printed Page.” Charles Ricketts, Everything for Art: Selected Writings, edited by Nicholas Frankel, Rivendale Press, 2014, pp. 77-81.

- Ricketts, Charles. A Defense of the Revival of Printing. Charles Ricketts, Everything for Art: Selected Writings, edited by Nicholas Frankel, Rivendale Press, 2014, pp. 95-112.

- —. “An Illustration to the King’s Quair.” The Dial, vol. 4, 1896, np. The Dial Digital Edition, edited by Lorraine Janzen Kooistra, Yellow Nineties 2.0, Ryerson University Centre for Digital Humanities, 2020. https://beta.1890s.ca/dialv4-ricketts-quair-AF/

- —. “Pan Hailing Psyche Across the River.” The Dial, vol. 5, 1897, np. The Dial Digital Edition, edited by Lorraine Janzen Kooistra, Yellow Nineties 2.0, Ryerson University Centre for Digital Humanities, 2020. https://beta.1890s.ca/dialv5-ricketts-psyche-af/

- —. “Prefatory Note to A Catalogue of Mr. Shannon’s Lithographs.” Charles Ricketts, Everything for Art: Selected Writings, edited by Nicholas Frankel, Rivendale Press, 2014, pp. 139-151.

- —. “The Vision of King James the First of Scotland.” The Dial, vol. 5, 1897, np. The Dial Digital Edition, edited by Lorraine Janzen Kooistra, Yellow Nineties 2.0, Ryerson University Centre for Digital Humanities, 2020. https://beta.1890s.ca/dialv5-ricketts-vision-AE/

- Shannon, Charles. “December.” The Dial, vol. 5, 1897, np. The Dial Digital Edition, edited by Lorraine Janzen Kooistra, Yellow Nineties 2.0, Ryerson University Centre for Digital Humanities, 2020. https://beta.1890s.ca/dialv5-shannon-december-aa/

- —. “The Dressing Room.” The Dial, vol. 5, 1897, np. The Dial Digital Edition, edited by Lorraine Janzen Kooistra, Yellow Nineties 2.0, Ryerson University Centre for Digital Humanities, 2020. https://beta.1890s.ca/dialv5-shannon-dressing-ab/

- —. “The Infancy of Bacchus.” The Dial, vol. 5, 1897, np. The Dial Digital Edition, edited by Lorraine Janzen Kooistra, Yellow Nineties 2.0, Ryerson University Centre for Digital Humanities, 2020. https://beta.1890s.ca/dialv5-shannon-frontispiece/

- Sturt, Charles [aka Charles Ricketts]. “Outamoro.” The Dial, vol. 5, 1897, pp. 21-26. The Dial Digital Edition, edited by Lorraine Janzen Kooistra, Yellow Nineties 2.0, Ryerson University Centre for Digital Humanities, 2020. https://beta.1890s.ca/dialv5-sturt-outamaro/

- White, Gleeson. “At the Sign of the Dial.” The Magazine of Art, January 1897, pp. 304-309. Yellow Nineties 2.0, edited by Lorraine Janzen Kooistra, Ryerson University Centre for Digital Humanities, 2020. https://www.1890s.ca/dial1-4-review-the-magazine-of-art-jan-1897/

- Woodring, Carl. “Centaurs Unnaturally Fabulous.” The Wordsworth Circle, vol. 38, nos. 1-2, Winter/Spring 2007, pp. 4-12. https://doi.org/10.1086/TWC24043951

MLA citation:

Kooistra, Lorraine Janzen. “Critical Introduction to Volume 5 of The Dial (1897)” The Dial Digital Edition, Yellow Nineties 2.0, 2019-2020, edited by Lorraine Janzen Kooistra, Ryerson University Centre for Digital Humanities, 2020, https://1890s.ca/dialv5_critical_introduction/