XML PDF

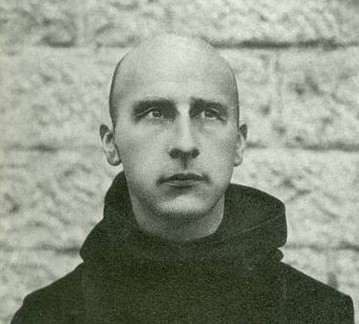

Oliver-Georges Destrée

(1867 – 1919)

Olivier-Georges Destrée, brother of socialist politician Jules Destrée (1863–1936), was a poet, art critic and translator, whose indefatigable enthusiasm and energy to promote the art and literature of others overshadowed his personal contribution to the literary scene of the late nineteenth century. Destrée was connected to Belgian networks Les XX and La Libre Esthétique and was also an eminent champion of Pre-Raphaelite art in Belgium. He developed artistic and literary connections in London. He also travelled extensively through Italy, Flanders, and the north of France, with companions such as the writer and critic Laurence Binyon (1869–1943) and his cousin Paul Tiberghien. A seeker and finder of art and culture, he contributed his translations, impressions, and analyses to Belgian, French, and British magazines, then turned his expertise and creativity towards religious topics, while he matured his decision to become a Benedictine monk in 1898. In later years, Destrée persevered in his resolve to transmit a literary legacy with another focus, this time on sacred art.

Georges Destrée was born in 1867 in the Belgian town of Marcinelle, the second son of an engineer, in a wealthy and well-connected family. In 1883, the Destrée brothers travelled to Italy with their father, where Georges discovered the Early Renaissance painters. He also developed an interest for anglophone intellectual circles, which he joined in Brussels with Tiberghien when they were still teenagers. The young Destrée was drawn to Wagner’s operas and especially seduced by medieval myths and the Arthurian ideals that pervaded Victorian anglophone poetry and literature. In 1886, he served as an interpreter for his family during a first trip to London. The Destrée brothers studied law at the Université Libre de Belgique. In the Belgian capital, they joined a network of ambitious young intellectuals among whom were Georges Eekhoud (1854–1927), André Fontainas (1865–1948), Iwan Gilkin (1858–1924), Albert Giraud (1860–1929), Arnold Goffin (1863–1934), Maurice Maeterlinck (1862–1949), Georges Rodenbach (1855–1898), Fernand Séverin (1867–1931), Charles Van Lerberghe (1861–1907), and Emile Verhaeren (1855–1916). This new literary generation contributed to little magazines such as La Jeune Belgique (1881-1897). Founded by Albert Bauwens (1861–1950) and directed by Max Waller (1860–1889), around the creed l’Art pour l’Art, La Jeune Belgique advocated for change and modernity, yet above all for the love of beauty. The group of young authors were connected to an international community of artists that dominated the Belgian artistic scene until the First World War: first known as Le Groupe des XX (or, Les XX), and later renamed La Libre Esthétique by the critic Octave Maus (1856-1919). In the meantime, Georges Destrée, who started adding his father’s name, Olivier, to his own, was acquiring a solid reputation as a specialist of anglophone culture. He published several translations of English poets in Belgian literary magazines, notably Tennyson’s “The Palace of Art” in the April 1894 issue of the Magasin littéraire et scientifique (1884–1898).

Destrée also wrote some original poetry, for instance the collection Poèmes sans rimes published in London in 1894. Yet his true calling was that of a promoter. He endeavoured to enrich the literary and artistic landscape of young Belgium with British work, and to introduce Belgian art in Britain. From 1889 he translated and annotated Pre-Raphaelite poetry in La Jeune Belgique and wrote his first book, Les Préraphaélites: Notes sur l’art décoratif et la peinture en Angleterre, published by Dietrich in Brussels in 1894. Destrée was the first Belgian to introduce Pre-Raphaelitism to his countrymen, and even among the first few who published on the subject in the French language, along with Gabriel Sarrazin (1853-1935) and Robert de la Sizeranne (1866-1932). The next year, he turned his efforts in the other direction, by publishing The Renaissance of Sculpture in Belgium with Seeley & Co. in 1895.

Acting on the increasing importance of cultural exchange with Britain, the Belgian government sent Destrée to London to report on the Arts and Crafts exhibition in 1894. Destrée’s stay confirmed his enthusiasm for the Pre-Raphaelite movement, then in full bloom in England, yet less well-known abroad. He was introduced to London’s literary and artistic circles and clubs. It was on one of these occasions that he met one of his closest friends, Laurence Binyon, through English poet and novelist Ernest Dowson, at the Fitzroy Settlement, a large Adam-style house in Fitzroy Street purchased by the architect and designer Arthur Heygate Mackmurdo (1851–1942) in 1889. The Fitzroy Settlement was to become at the turn of the century one of the most thrilling environments for artistic and intellectual London life. Binyon and Destrée’s friendship thereby began in the very centre of late-Victorian culture. Binyon benefited from a solid reputation as a poet and an art critic within a wide network of English artists who made up the rising generation of London artistic life. The correspondence between the two men lasted until Destrée’s death, but was most prolific between 1895 and 1898, when they wrote to each other several times a week and spent the time they could visiting each other and travelling together. Both were admirers and scholars of Victorian art, yet they belonged to the generation of authors who contributed to a turning point in the European artistic world as it opened to foreign (especially Flemish and Italian) influences, and evolved towards modernism. Binyon opened many doors for Destrée in England, for example by introducing him to his intimate friends Mackmurdo (mentioned above), Herbert Percy Horne (1864-1916) and Selwyn Image, who were members of the Century Guild of Artists. Their artistic eclecticism and craftsmanship prefigured the Art Nouveau and were forerunners of the Arts and Crafts movement. Binyon also introduced Destrée to William Butler Yeats (1865-1939), Lionel Johnson, and Victor Plarr (1863–1929), members of the Rhymer’s Club, founded by Yeats and Ernest Rhys (1859–1946) in 1890.

A big project that forms the bulk of Destrée and Binyon’s correspondence, and which had already started as early as 1887, is Destrée’s anthology of nineteenth-century English poetry. The exact working title was Anthologie des poètes anglais du XIXe siècle. Traductions littérales, accompagnées de notices biographiques et critiques de poèmes de: Blake, Rogers, Wordsworth, Scott, Coleridge, Southey, Lamb, Landor, Campbell, Moore, Lord Byron, [Charles] Wolfe, Shelley, Keats, Hood, Lord Tennyson, E. B. Browning, R. Browning, E. Brontë, M. Arnold, D. G. Rossetti, Morris, Swinburne. As indicated in the title, Destrée carefully annotated, and translated all these poems himself. Despite numerous attempts to get this work published, it remained a manuscript. Only a few notices and translations appeared here and there in Belgian periodicals. During these years, however, Destrée published several poems and articles for foreign magazines, including an obituary of William Morris (1834–1896) in the Mercure de France (Nov. 1896). In England, Destrée published an article on “The Stained Glass Windows and Decorative Paintings of the Church of St. Martin’s-on-the-Hill” by Pre-Raphaelite artists in The Savoy (Oct. 1896), and on Belgian sculpture in The Dome (Sept. 1897), Binyon helping with the English translation. These articles demonstrate Destrée’s knowledge and connections in the world of art, and his ambition to contribute to a cross-fertilization between British and Belgian culture, art, and intellectual networks. Like many artists, cultural agents such as Binyon and Destrée also struggled with financial issues. There were no fixed rules as to remuneration in the publishing world, and Destrée had to make a living from his writing, as Binyon explains in a letter about the publication in The Dome: “It is not a good magazine, but pays quite well!” (Letter from Binyon to Destrée, BL Archive collection (LTR #63, August 14, 1897)).

During one of his first visits to London, Destrée met the painter Edward Burne-Jones (1833–1898), who made a great impression on the young scholar by telling him about the life of Father Damian (1840–1889), a now canonized Belgian priest who committed his life to the care of lepers in Hawaii. Destrée had been raised an agnostic. The beauty of Father Damian’s religious devotion resonated with his artistic sensitivity—it imbued his early adherence to “art for art’s sake,” which had matured into a consideration of Pre-Raphaelite art, with a more profound meaning. He later confessed his feeling that a form of transcendence, which he found in the great Russian authors, was lacking in British literature. Destrée shared the story of Father Damien with Paul Tibergien. The cousins enthusiastically read the Gospels together during trips to Italy, and both started to commit to the idea of a religious career, while they followed catechism classes from 1896 with the charitable institution Saint-Vincent-de-Paul-des-Minimes in Brussels. The work Destrée produced became markedly religious: in addition to “Les Mages,” he published biographies of “Sainte Dorothée de Cappadoce” and “Saint Jean Gualbert Visdomini,” inspired by paintings by Burne-Jones, and a poetic entry on “Sainte Rose de Viterbe” in the December 1897 issue of the Belgian Spectateur Catholique (1897–1900). At some point in the Spring of 1898, Destrée firmly decided to devote his life to God. First, he considered priesthood, but then made the more radical choice of the monastery. Perhaps he needed a more stable professional and personal situation, in a secluded atmosphere that would enable him to pursue some literary activities. This decision had been discussed with his cousin, who made a similar religious commitment. Binyon was terribly upset, not so much out of anti-Catholic prejudice, though he never understood his friend’s religious calling, but because he knew it would cut short a friendship which had lightened up a great part of his life.

Destrée was not the only Belgian intellectual to attempt to bridge the gap between pure aesthetics and the ideal of beauty as a kind of religion. The 1891 encyclical Rerum novarum by Pope Leo XIII gave a new impulse to political Catholicism in Belgium. The Congress of Mechelen (1891) established the political existence of a group of Young Catholics who took a keen interest in literature. The creation and success of the resulting little magazine Durendal (1894–1914), to which Destrée contributed regularly, especially in later years, coincided with the political domination of the Catholic Party in Belgium. The creation of Durendal was also the result of a merged effort with several adherents of La Jeune Belgique to transcend the formula “l’Art pour l’Art.”

Destrée spent the first year of his new life in the abbey of Maredsous (near Namur, Belgium) before moving to the Mont César/Keizersberg abbey in the town of Leuven, Belgium, where he was ordained in 1903, under the name Dom Bruno. He contributed to the international dissemination of Catholic art and became an authority on the subject, while he published several books on religious and spiritual topics: La Mère Jeanne de Saint-Mathieu Deleloë: une mystique inconnue du XVIIIe siècle (1904), Au milieu du chemin de notre vie (1908), Les Bénédictins (1910), L’Âme du Nord (1911), Impressions et Souvenirs (1913). He painstakingly collected materials from home and abroad to include in an exhaustive survey of Catholic art, while he worked for several international exhibitions, including, in 1911, “Les Arts Anciens du Hainaut,” with his brother Jules Destrée, and the 19th international exhibition of religious art of the Société Royale des Beaux Arts in Brussels, in June 1912. During the tragic night of the burning of Louvain in August 1914 at the start of WWI, Destrée escaped the fire, but his manuscript on religious art was destroyed. He died shortly after the war, in 1919, of peritonitis, at the age of 52.

©2022, Eloïse Forestier, FWO postdoctoral researcher, Ghent University, Belgium.

Selected Publications by Olivier Georges Destrée:

Poetry:

- Au milieu du chemin de notre vie. Librairie Albert Dewit, 1921 (1908).

- Journal des Destrée. Paul Lacomblez, 1891.

- Impressions et souvenirs. Bloud, 1913.

- Poèmes sans rimes. Presses of Chiswick, 1894.

Books:

- L’Âme du Nord. Action Catholique, 1911.

- La Mère Jeanne de Saint-Mathieu Deleloë: une mystique inconnue du XVIIIe siècle. Société Saint Augustin, Desclée, De Brouwer et Cie, 1905 (1904).

- Les Bénédictins. Abbaye du Mont César et Louvain, 1910.

- Les Préraphaélites: notes sur l’art décoratif et la peinture en Angleterre. Dietrich, 1894.

- L’Orfèvrerie religieuse: l’œuvre de Jan Brom. Abbaye du Mont César et Louvain, 1913.

- The Renaissance of sculpture in Belgium. Seeley & Co., 1895.

Periodical Publications (translations, articles, and poems):

- “Christina-Georgina Rossetti.” Durendal, vol. 5, October 1898, pp. 885-888.

Digithèque de l’ULB: Périodiques numérisés,

https://digistore.bib.ulb.ac.be/2012/ELB-AML-484382-1898-000-005_f.pdf

- “Chronique Artistique: Le Salon Éternel.” La Jeune Belgique, vol. 9, October

1890, pp. 373-378. Digithèque de l’ULB: Périodiques numérisés,

https://digistore.bib.ulb.ac.be/2012/ELB-ULB-516421-1890-001-009_f.pdf

- “Chronique Artistique: Les Aquarellistes.” La Jeune Belgique, vol. 9, January

1890, pp. 93-94. Digithèque de l’ULB: Périodiques numérisés,

https://digistore.bib.ulb.ac.be/2012/ELB-ULB-516421-1890-001-009_f.pdf

- “Chronique Artistique: Exposition Artan-Dubois-Boulenger.” La Jeune Belgique,

vol. 10, February 1891, pp. 123-125. Digithèque de l’ULB: Périodiques numérisés,

https://digistore.bib.ulb.ac.be/2012/ELB-ULB-516421-1891-001-010_f.pdf

- “Le Palais de l’Art, traduction de Tennyson.” Le Magasin littéraire et

scientifique, vol. 1, April 1984, pp. 273-282. Digithèque de l’ULB: Périodiques

numérisés,

https://digistore.bib.ulb.ac.be/2013/ELB-KBR-a0104-1884-000.pdf

- “Les Cloches.” La Jeune Belgique, vol. 10, January 1891, pp. 65-69. Digithèque

de l’ULB: Périodiques numérisés,

https://digistore.bib.ulb.ac.be/2012/ELB-ULB-516421-1891-001-010_f.pdf

- “Les Mages.” Durendal, vol. 6, June 1899, pp. 483-495; July 1899, pp. 527-536;

August 1899, pp. 613-624; September 1899, pp. 677-688. Digithèque de l’ULB:

Périodiques numérisés,

https://digistore.bib.ulb.ac.be/2012/ELB-AML-484382-1899-000-006_f.pdf

- “Les panneaux décoratifs d’Aug. Donnay pour l’église d’Hastière.” Durendal,

vol. 19, 1912, pp. 466-468. Digithèque de l’ULB: Périodiques numérisés,

https://digistore.bib.ulb.ac.be/2012/ELB-AML-484382-1912-000-019_f.pdf

- “Orgueil.” La Jeune Belgique, vol. 9, January 1890, pp. 63-64. Digithèque de

l’ULB: Périodiques numérisés,

https://digistore.bib.ulb.ac.be/2012/ELB-ULB-516421-1890-001-009_f.pdf

- “Proses.” La Jeune Belgique, vol. 10, May 1891, pp 206-210. Digithèque de

l’ULB: Périodiques numérisés,

https://digistore.bib.ulb.ac.be/2012/ELB-ULB-516421-1891-001-010_f.pdf

- “Quatre Poèmes de Christina Rossetti (traduction).” Durendal, vol. 5, January

1898, pp. 41-44. Digithèque de l’ULB: Périodiques numérisés,

https://digistore.bib.ulb.ac.be/2012/ELB-AML-484382-1898-000-005_f.pdf

- “Sainte Dorothée de Cappadoce”; “Sainte Rose de Viterbe”; “Saint Jean

Gualbert.” Le Spectateur Catholique, vol. 1, December 1897, pp. 241-252.

Digithèque de l’ULB: Périodiques numérisés,

https://digistore.bib.ulb.ac.be/2013/ELB-ULB-a0105-1897-001-0001.pdf

- “Some Notes on the Stained-glass Windows and Decorative Paintings of the Church of St. Martin’s-on-the-hill, Scarborough.” The Savoy, vol. 6, October 1896, pp. 76-90. Yellow Nineties 2.0, https://1890s.ca/wp-content/uploads/savoy_1896_06.pdf

- “Stances à Saint Pierre.” Durendal, vol. 5, January 1898, pp. 98-101.

Digithèque de l’ULB: Périodiques numérisés,

https://digistore.bib.ulb.ac.be/2012/ELB-AML-484382-1898-000-005_f.pdf

- “Sur le Rivage.” Durendal, vol. 5, September 1898, pp. 814-815. Digithèque de

l’ULB: Périodiques numérisés,

https://digistore.bib.ulb.ac.be/2012/ELB-AML-484382-1898-000-005_f.pdf

- “The Revival of Chryselephantine Sculpture in Belgium.” The Dome, September 1897, pp. 17-22. ProQuest British Periodicals

- “Vénus Aphrodite.” La Jeune Belgique, vol. 10, July 1891, pp. 264-266.

Digithèque de l’ULB: Périodiques numérisés,

https://digistore.bib.ulb.ac.be/2012/ELB-ULB-516421-1891-001-010_f.pdf

- “William Morris, avec un portrait de William Morris d’après G.-F. Watts.”

Mercure de France, vol. XX, n. 83, November 1896, pp. 272-291. Retronews,

https://www.retronews.fr/journal/mercure-de-france/01-novembre-1896/118/4093419/1

- “VIIe Exposition des XX: Xavier Mellery.” La Jeune Belgique, vol. 9, February

1890, pp. 125-127. Digithèque de l’ULB: Périodiques numérisés,

https://digistore.bib.ulb.ac.be/2012/ELB-ULB-516421-1890-001-009_f.pdf

Selected Publications about Olivier-Georges Destrée:

- Brogniez, Laurence. “Georges-Olivier Destrée et la religion de l’art: de l’esthète au converti.” Edited by Alain Dierkens, Problèmes d’histoire des religions: dimensions du sacré dans les littératures profanes, vol. 10, Éditions de l’université de Bruxelles, 1999, pp. 33-42.

- Carton de Wiart, Henri. La Vocation d’Olivier Georges Destrée. Flammarion, 1931.

- Goffin, Arnold. “Olivier-Georges Destrée.” Durendal, vol. 5, December 1898, pp.

991-1000. Digithèque de l’ULB: Périodiques numérisés,

https://digistore.bib.ulb.ac.be/2012/ELB-AML-484382-1898-000-005_f.pdf

- Demoor, Marysa and Frederick Morel. “Laurence Binyon and the Belgian Artistic

Scene: Unearthing Unknown Brotherhoods.” Victorian Periodicals Review, vol. 44, n.

2, Summer 2011, pp. 184-197. Jstor,

https://www.jstor.org/stable/23079124

- Forestier, Eloise; Marysa Demoor and Gero Guttzeit. “A Transnational Literary

Network Around 1900, the Correspondence between Laurence Binyon and

Olivier-Georges Destrée.” Scholarly Editing, May 2016.

http://scholarlyediting.org

- Nothomb, Pierre. Une Conversion Esthétique: Olivier Georges Destrée. Librairie de l’action catholique, 1910.

- Turquet-Milnes, Gladys Rosaleen. Some Modern Belgian Writers: A Critical Study. Books for Libraries Press, 1968.

- Van Houtryve, Idesbald. Biographie nationale, t. 33. Établissement Émile

Bruylant, 1965, pp. 247-251. Biographie nationale: Académie royale de Belgique,

https://www.academieroyale.be/academie/documents/FichierPDFBiographieNationaleTome2092.pdf

MLA citation:

Forestier, Eloïse . “Olivier-Georges Destrée (1867–1919),” Y90s Biographies. Yellow Nineties 2.0, edited by Lorraine Janzen Kooistra, Toronto Metropolitan University Centre for Digital Humanities, 2023, https://1890s.ca/destree_bio/.