XML PDF

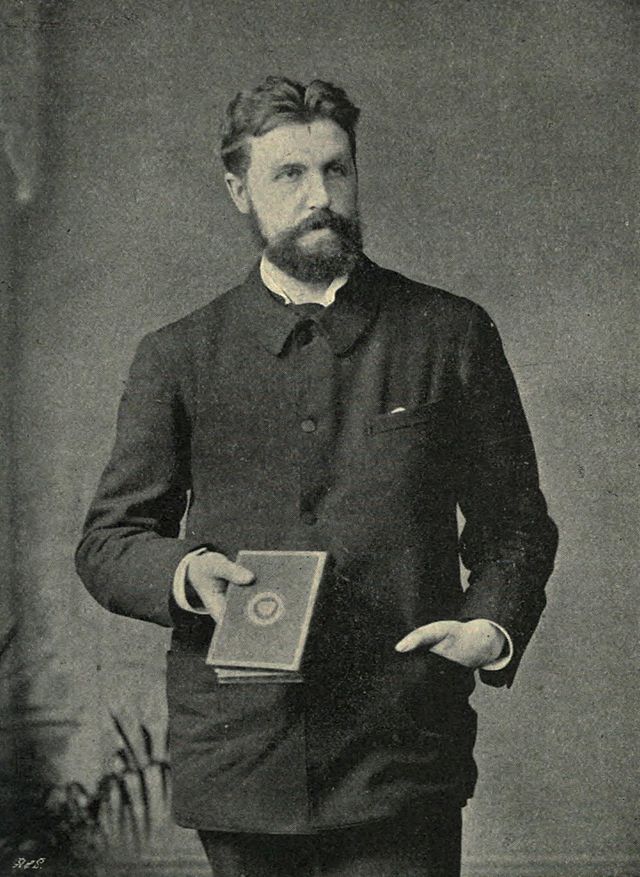

Samuel Rutherford Crockett

(1859 – 1914)

Samuel Rutherford Crockett was born Samuel Crocket on 24 September 1859 in Little Duchrae, in the parish of Balmaghie, Kirkcudbrightshire, Galloway. His mother was Anne Crocket, a dairymaid, and his father was rumoured to be a local farmer, David Blaine Crockett. He was raised by his grandparents, William and Mary Crocket, on their farm, and was particularly influenced by their devout Cameronian beliefs, going back to a late-seventeenth-century faction of religious radicals led by Richard Cameron, who were dissatisfied with moderate Scottish Presbyterianism. Crockett was educated at Laurieston School, about three miles from his home, and the family attended the Reformed Presbyterian Church in Castle Douglas. In 1867 they permanently moved to Castle Douglas, where Crockett attended the local Free School and became an apprentice teacher, known as a pupil teacher. At the age of fifteen, he won the Galloway Bursary to study at the University of Edinburgh. To supplement this bursary, he tutored and published stories and articles in various magazines and newspapers in Edinburgh (Nash 91). In 1878, he spent the summer looking for work as a journalist in London, but was unsuccessful, and returned to Edinburgh to work as a tutor. He travelled extensively in Europe with his tutees between 1879 and 1881.

Crockett enrolled at New College, Edinburgh, in 1881–82, and graduated four years later as a Free Kirk minister. In 1886 he was licensed by the Free Presbytery of Kirkcudbright and elected to Penicuik, where he met Ruth Milner (1860–1932), the daughter of a Lancashire mill owner. They were married at Prestwick, Lancashire, in March 1887, and had two sons and three daughters. Their eldest daughter, Ruth Mary Rutherford Crockett (1888–1957), also became a successful novelist under the pseudonym Rutherford Crockett. In Penicuik, Rev. Crockett was active in the Good Templars, a fraternal organisation in the temperance movement, and was a regular lecturer at Sabbath Associations across Scotland.

Crockett was a highly versatile writer during a highly productive era in Scottish fiction. From the 1870s, the Scottish periodical press experienced unprecedented levels of growth, which resulted in a popular and mass-produced magazine and newspaper culture (Harris, 2007; Donaldson, 1989). Crockett published in a variety of magazines, periodicals, and newspapers, and his career is defined by his ability to adapt to these titles and to the literary tastes of the wider reading public. A self-professed “popular writer” (Aitken 63), his work reflects the popularity of a variety of current in the late Victorian era. The most important of these was the Kailyard School—fiction in the 1880s and 1890s that sentimentalised rural Scottish life using heavy Presbyterian overtones. Others include the clerical novel, the regional novel, the industrial novel, historical fiction, tales of adventure, and romance fiction.

Crockett’s career trajectory follows a familiar pattern of popular Scottish writers in the late-nineteenth century. His first publication was a volume of poetry, Dulce Cor (1886), which was self-published under his pseudonym Ford Berêton and from which selected poems appeared in the edited collection The Bards of Galloway (1889). Subsequently, he contributed to the periodical press as a journalist. He was the editor of The Workers’ Monthly (1890), a Christian socialist magazine for Sunday School teachers, to which he contributed almost all the articles (Nash 91).

Crockett’s experience as the local minister during the colliery disaster at Mauricewood Pit in 1889, near Penicuik in southeast Scotland, inspired an interest in the industrial novel. In 1890 he published “The True Story of the Penicuik Pit Laddies” in The Workers’ Monthly, and, in 1907, “Vida; or, The Pit Lads of Kirkton” in the People’s Friend (1869–), a popular weekly magazine known for its short fiction. He was a regular contributor to The Christian Leader (1882-1905), a weekly Glasgow newspaper, where his sketches of parish life in Lowland Scotland first appeared and were later published as The Stickit Minister and Some Common Men in 1893. The Stickit Minister was followed by The Lilac Sunbonnet (1894), which sold 10,000 copies on its day of publication (Nash 110), and these secured Crockett’s association with the Kailyard School. This association was also encouraged by his connection with London-based journalist and former Free Kirk minister William Robertson Nicoll, who championed the popularisation of other Scottish authors associated with the Kailyard, such as J. M. Barrie (1860–1937), Annie S. Swan (1859–1943), and Rev. John Watson [Ian Maclaren] (1850–1907). Although the Kailyard was criticised by literary critics such as J. H. Millar (1864–1929)—who first coined the pejoratively intended term in 1895 (Nash 40)—and lambasted by Hugh MacDiarmid (1892–1978) (Campbell 123–124), the Kailyard was highly popular with readers in Britain and North America and immensely productive for Scottish publishers, magazines, and newspapers (Donaldson 145–148). Scholarly reappraisals of Crockett’s Kailyard works have found connections to the clerical novel, vernacular sketches and dialect literature, Nonconformism, and European decadence (Nash 97, 103; Lauder). In 1894, Crockett resigned from his position as a minister and began writing full-time.

Crockett was deeply interested in the regional novel, and Galloway and Balmaghie were the inspiration for several of his books, including Bog-Myrtle and Peat (1895), Lochinvar (1897), The Standard Bearer (1898) and Raiderland (1904). He was also a writer of historical fiction and adventure tales, such as The Men of Moss Hags (1895), The Grey Man (1896), and The Black Douglas (1899). Crockett’s travels to Europe appeared to support his interest in stories of travel and adventure. In a Vanity Fair (1868-1914) caricature from August 1897, he is depicted as the rugged, adventuring writer in a travelling overcoat, its cape moving through the air, his hair in motion, with a copy of The Lilac Sunbonnet in hand. Crockett was a frequent traveller and an active man—he liked alpine climbing—but, uncharacteristically of his public persona, he also sought respite in the warmer climate of Europe to recover from frequent periods of ill-health and disease, including influenza, malaria, and enteritis.

Crockett was heavily dependent on magazine culture and the serialisation of his novels in the periodical press. These include “Kit Kennedy; or, The Waif of Galloway” (1899), “Cinderella; or, The Fortunes of Hester Stirling, A Countryside Romance” (1900), and “Flower-o’-the-corn. A Historical Romance” (1902), which were all published in the People’s Friend. In the English press, he published “Little Anna Mark” in The Cornhill Magazine (1899), “The Dark of the Moon” in The Graphic (1901), and “The Pest of the Village” in the Leeds Mercury (1902). Following their serialisation, some of these novels were later published in book form, such as Kit Kennedy: Country Boy (1899), Vida; or, The Iron Lord of Kirktown (1907), and Little Anna Mark (1900). Several of Crockett’s novels were also serialised in local Scottish newspapers, which were important sites of popular fiction in the late nineteenth century. The Red Axe (London: 1898) was serialised in the Glasgow Weekly Mail (1862-1915) in 1898, and Rose of the Wilderness (1909) was serialised in the Buchan Observer (1893-1988) in 1909. Like many other serving and former Scottish Presbyterian ministers, Crockett continued to publish fiction in religious periodicals, such as Good Words (1860–1907), Sunday at Home (1854–1939), and The Christian World (1866–1889).

Crockett’s association with the Edinburgh-based little magazine The Evergreen: A Northern Seasonal was brief. As he was a popular novelist who published in mainstream literary magazines, his contribution in this avant-garde publication seems paradoxical. Although he was not associated with the Scottish Renaissance of the late-Victorian era, however, there are several important similarities between The Evergreen and Crockett’s work, specifically regionalism, history, the environment, and Scottish national identity. Crockett’s poem, “ The Song of Life’s Fine Flower ,” appears in The Evergreen ’s Autumn volume of 1895, in the section “Autumn in the World.” It was later included in a collection of Crockett’s poetry, The Bloom o’ the Heather (1908), under a different title, “Proem.” The poem makes for an atypical contribution to The Evergreen because it describes Crockett’s honeymoon to Italy in March 1887 and a return visit to Italy during the spring of 1895. The poem, too, is something of a paradox. On the one hand, it is a celebration of love, the Italian landscape, and newly married life. On the other hand, the poem’s primary theme is decline. Crockett reflects on the decline of Italy and the fading remnants of the Roman Empire, despite the relatively recent Risorgimento and unification of Italy in 1871. In this way, his poem overlaps with the decadent mode as it appears in the early Scottish Renaissance, full of impassioned declinism and hope for cultural revival, as explained by Michael Shaw (24–25). Towards the end of the poem, Crockett poses an ambiguous question about how society characterises what is “old” and “new.” This very neatly summarises much of Crockett’s work: his romance fiction, Kailyard works, and historical tales of Galloway convey an idealised version of old Scotland that celebrates a preserved rurality, idyllic romanticism, and devout religious past. In the context of The Evergreen, Crockett’s poem appears contemporaneous with fin-de-siècle revivalist culture and the renewal of Scottish literary culture in light of its European and pan-Celtic connections.

Crockett’s final years were spent in frailty and ill-health. In 1913, he was seriously ill in the south of France, but recovered and was reported fit and well. He remained in France and died on 16 April 1914 at Avignon, to be buried at Balmaghie Kirk on 24 April. In announcing his death, one newspaper described him as “the figure-head in the literary movement that promised at the outset to give a new distinction to Scotland in a line of literary achievement that represented the true life of the people among whom he was born and bred” (“Death of a Famous Novelist” 6). In other obituaries, comparisons were frequently drawn between him and Robert Louis Stevenson (1850-1894), another beloved Scottish author and more specifically adventure novelist who died young, and whose literary connections outside of Scotland were widespread.

©2021, Charlotte Lauder, University of Strathclyde and National Library of Scotland

Charlotte Lauder is an AHRC-funded PhD student at the University of Strathclyde and National Library of Scotland, researching Scottish literary magazines, 1870-1920. She is a member of the Scottish Revival Network, an associate of the Scottish Centre for Victorian and Neo-Victorian Studies, and an advisory board member of the Scottish Magazines Network. Her work on Scottish women’s magazines has been featured on BBC Radio Scotland and BBC Scotland News.

Selected Publications by S. R. Crockett

- The Black Douglas. London: Smith, Elder, 1899.

- Bloom o’ the Heather. London: E. Nash, 1908.

- Bog-Myrtle and Peat, Being Chiefly Tales of Galloway, gathered from the years 1889 to 1895 . London: s. n., 1895.

- Cinderella. London: James Clarke, 1901.

- Cleg Kelly: Arab of the city: his progress and adventures. London: Macmillan, 1896.

- The Dark o’ the Moon: Being Certain Further Histories of the Folk Called “Raiders”. London: Macmillan, 1902.

- Dulce Cor: Being the Poems of Ford Berêton. London: Kegan Paul Trench, 1886.

- Flower o’ the Corn. London: James Clarke, 1902.

- The Grey Man. London: T. Fisher Unwin, 1896.

- Kit Kennedy. London: James Clarke, 1899.

- The Lilac Sunbonnet. London: T. Fisher Unwin, 1894.

- Little Anna Mark. London: s.n., 1900.

- Lochinvar. London: Methuen, 1897.

- Men of the Moss Hags. London: Macmillan, 1895.

- The Moss Troopers. London: Hodder & Stoughton, 1912.

- Raiderland: All About Grey Galloway: its Stories, Traditions, Characters, Humours. London: Hodder & Stoughton, 1904.

- The Red Axe. London: s.n., 1898.

- Rose of the Wilderness. London: Hodder & Stoughton, 1909.

- “The Song of Life’s Fine Flower,” The Evergreen. A Northern Seasonal, vol. 2, Autumn 1895, pp. 75–80. Evergreen Digital Edition, edited by Lorraine Janzen Kooistra, 2016-2018. Yellow Nineties 2.0, Ryerson University Centre for Digital Humanities, 2019. https://1890s.ca/egv2_crockett_song/

- The Stickit minister and Some Common Men. London: T. Fisher Unwin, 1893.

- Vida; or, The Iron Lord of Kirktown. London: James Clarke, 1907.

Selected Publications about S. R. Crockett

- Aitken, Charles. “An Appreciation of the Writings of S. R. Crockett.” Scots Magazine, 1 August 1897, pp. 63–68.

- Campbell, Ian. Kailyard. Edinburgh: Ramsay Head Press, 1981.

- “Death of a Famous Novelist.” Aberdeen Evening Express, 21 April 1914, p. 6.

- Donaldson, William. Popular Literature in Victorian Scotland: Language, Fiction and the Press. Aberdeen: University of Aberdeen Press, 1986.

- Donaldson, Islay M. The life and work of Samuel Rutherford Crockett. Aberdeen: Aberdeen University Press, 1989.

- Harris, Bob. “The Press, Newspaper Fiction and Literary Journalism, 1707–1914.” The Edinburgh History of Scottish Literature: Enlightenment, Britain and Empire: 1707-1918, edited by Susan Manning, Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2007, pp. 308–316.

- Lauder, Charlotte. “Scottish Cosmopolitanism and the Kailyard.” The History of Scottish Cosmopolitanism at the Fin de Siècle, University of Glasgow, October 2020, https://scoco.glasgow.ac.uk/events/event-2/. Accessed 4 June 2021.

- McLachlan Harper, Malcolm. Crockett and Grey Galloway: The Novelist and his Work. London, s.n., 1907.

- Nash, Andrew. Kailyard and Scottish Literature. New York: Rodopi, 2007.

- Phillips, Cally. Discovering Crockett’s Galloway. Turriff: Ayton Publishing Ltd., 2015.

- Shaw, Michael. The Fin-de-Siècle Scottish Revival: Romance, Decadence and Celtic Identity. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2019.

MLA citation:

Lauder, Charlotte. “Samuel Rutherford Crockett (1859–1914),” Y90s Biographies. Yellow Nineties 2.0 , edited by Lorraine Janzen Kooistra, Ryerson University Centre for Digital Humanities, 2021, https://1890s.ca/crockett_bio/.