Mabel Syrett

(1871 – 1961)

Of the three Syrett sisters —Netta, Mabel and Nellie —who contributed to The Yellow Book (collectively, volumes 2, 7, 10, 11, 12, and 13), artist and illustrator Mabel Syrett is the most obscure. A talented student of the arts from a young age, she was born in June 1871 in Harbour Street, Ramsgate, Kent, the fifth of a total of 13 children of Ernest Syrett (d. 1906), draper and silk merchant, and Mary Ann, née Stembridge (d. 1923), ( 1871 England Census). Mabel was the niece of writer Grant Allen (1848–1899), and her sisters included prolific author Netta Syrett (1865-1943) and artist Nellie Syrett (1874-1970). The family lived comfortably and her parents, unusually for the time, supported their daughters’ choice of higher education, formal training and creative careers. Like her sister Nellie, Mabel became an illustrator of quarterlies and (reportedly) children’s books. While Netta has an entry in the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography and Nellie has an entry in Artist Biographies, British and Irish Artists of the 20th Century , Mabel has no known biographical entry elsewhere and any information on her is extremely scarce.

When the siblings moved to London to access training and employment, they shared a household, sometimes with other family members as well. Netta, Mabel, and Nellie – the three sisters who contributed to The Yellow Book —lived at 3 Morpeth Terrace, Westminster (close to Westminster Cathedral) from mid-decade to the early twentieth century. According to 1901 census records, Netta, the eldest at age 36, is listed as head of household, account owner, and “Novelist Author”; Mabel is recorded as a 29-year-old “Artist Fabric designer”; and 26-year-old Nellie is listed as “Artist” ( 1901 England Census). A decade earlier, the 1891 census records document Netta, Mabel, Georgiana, and their brother Ernest Frank Syrett living together at a nearby address: 1 to 14 Ashley Gardens, Ambrosden Avenue, London. Here Netta is listed as “Journalist Author” and Mabel as “Art Student, Drawing” ( 1891 England Census). In the absence of memoirs, the occupation entries on census records trace the development of Mabel’s creative career and identity from an art student focused on drawing to a professional artist and fabric designer. Her sister Kate (who attended Bedford College before pursuing an art career in Paris) designed costumes for Netta’s plays, Nellie illustrated Netta’s stories, and Mabel, Nellie and Netta all contributed to The Yellow Book. These well-connected, cohabiting and collaborating sisters formed a career-enabling familial coterie that was part of a wider fin-de-siècle community of magazine contributors, authors, and artists.

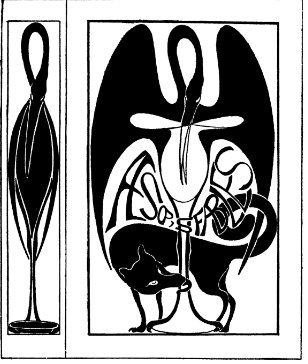

The Syrett sisters’ literary and visual contributions spanned the production years of The Yellow Book, from Netta’s involvement at its inception in 1894 to Mabel’s controversial debut at its end in 1897. In Netta’s view, the infamous Yellow Book phase of London literary life was “killed by Oscar Wilde’s tragedy” and its art editor Aubrey Beardsley’s subsequent move to The Savoy (N. Syrett 95). Yet all three sisters contributed to The Yellow Book after Wilde’s trial in 1895, indicating a sororal intervention in a publication previously associated with male Aesthetes. Mabel designed the front cover image (repeated on the back) for the final issue of The Yellow Book in April 1897, marking the end of the publication’s 13-volume run. This volume features literary contributions from well-known writers of the time, including W. B. Yeats (1865-1939), Ella D’Arcy (1851-1939/1857-1937), Stephen Phillips (1864-1915), and Evelyn Sharp (1869-1955). It contains illustrations by women artists such as Slade-trained Amelia Bauerle (1873-1916), whose work is comparable in its avian imagery, American graphic artist Ethel Reed (1874-1912), and Scottish artist Katharine Cameron (1874-1965). It also contains works by male artists Charles Conder (1868-1909), Muirhead Bone (1876-1953), E. J. Sullivan (1869-1933), and Patten Wilson (1869-1934). Of all the art contributions, Mabel’s cock-fight cover design is by far the most striking, affording it front-cover status (fig. 1).

However, Mabel’s “two game-cocks […] in deadly combat” received a scathing review in the Dundee Advertiser of 1897: “future generations will not mistake it for the work of genius, for the reader is gravely informed that it is from a design by Mabel Syrett” (“Current Fiction,” 2). Her cover was not well received in the U.S., either: an article of the same year titled “Bad Art in the Yellow Book” in the New York Times comments on Mabel’s “two fighting cocks, with all kinds of undulating tail feathers, but with very poorly developed spurs” (“ Bad Art,” BR5). This may reflect male critics’ prejudice against a relatively obscure female artist gracing the final cover of a high-profile periodical, rather than Mabel’s lack of creative talent or output, which is elsewhere applauded. Indeed, the opening lines of a contemporary article from The Literary World call Mabel’s cover design “startling,” and the concluding note of an article from The Academy – which traces the decline of The Yellow Book’s art, apparently evidenced by the contents of the final volume – praises Mabel’s deft manipulation of two fighting cocks (“ The Yellow Book,” 245). The energy of Mabel’s bold, graphic work lies in the birds’ flamboyant tails, which rise dramatically and descend in decorative art-nouveau spirals. The interlocking avian forms suggest intimacy rather than aggression, perhaps accounting for the undeveloped spurs. Mabel’s cocks depart from the more familiar peacock designs popular with Aestheticism. Hers is more comparable with Walter Crane’s famous Swan, Rush and Iris wallpaper design of 1875: two facing swans against a stylised background, featuring heraldic formality, black outlines and solid blocks of colour. Crane’s designs often drew on myths, fairy tales, and nursery rhymes. One influence for Mabel’s design may have been ‘The Fighting Cocks and the Eagle’ from Aesop’s Fables (illustrated by both Mabel and Walter Crane, discussed below), conveying the ancient admonition ‘pride goes before a fall’. The recent ban on cockfighting in Scotland in 1895 (long after England in 1835) may have been another influence.

During the rise of Mabel’s career, genius was more often attributed to male artists, and in the context of her family, to Netta. Yet Mabel’s genius was a subject of debate in contemporary newspaper articles, revealing her cultural influence – and the public interest she generated – at the fin de siècle. A 1901 gossip column in The Cornish and Devon Post (“Gossip,” 6) discusses Mabel in the “Woman’s Realm” along with distinguished female figures like Queen Alexandra as well as cutting-edge fashion. It identifies Mabel as the “very clever sister” of successful playwright Netta, whose books she illustrated, claiming that genius ran in the family. While this article suggests that they both studied at the Slade School of Art, and Netta writes in her autobiography that Mabel and Nellie went to art schools (N. Syrett 67), the Slade records only confirm Nellie’s attendance. The newspaper’s correspondent, who apparently trained with the sisters, offers insight into Mabel’s exceptional artistic skill, recalling the Slade professor’s praise of her original drawing and how “the most ordinary subjects acquired a grace of their own in her hands” (“Gossip”, 6). The article acknowledges Mabel’s success as “an artist in black and white,” alluding to the influence of Aubrey Beardsley, whilst acknowledging her an artist in her own right.

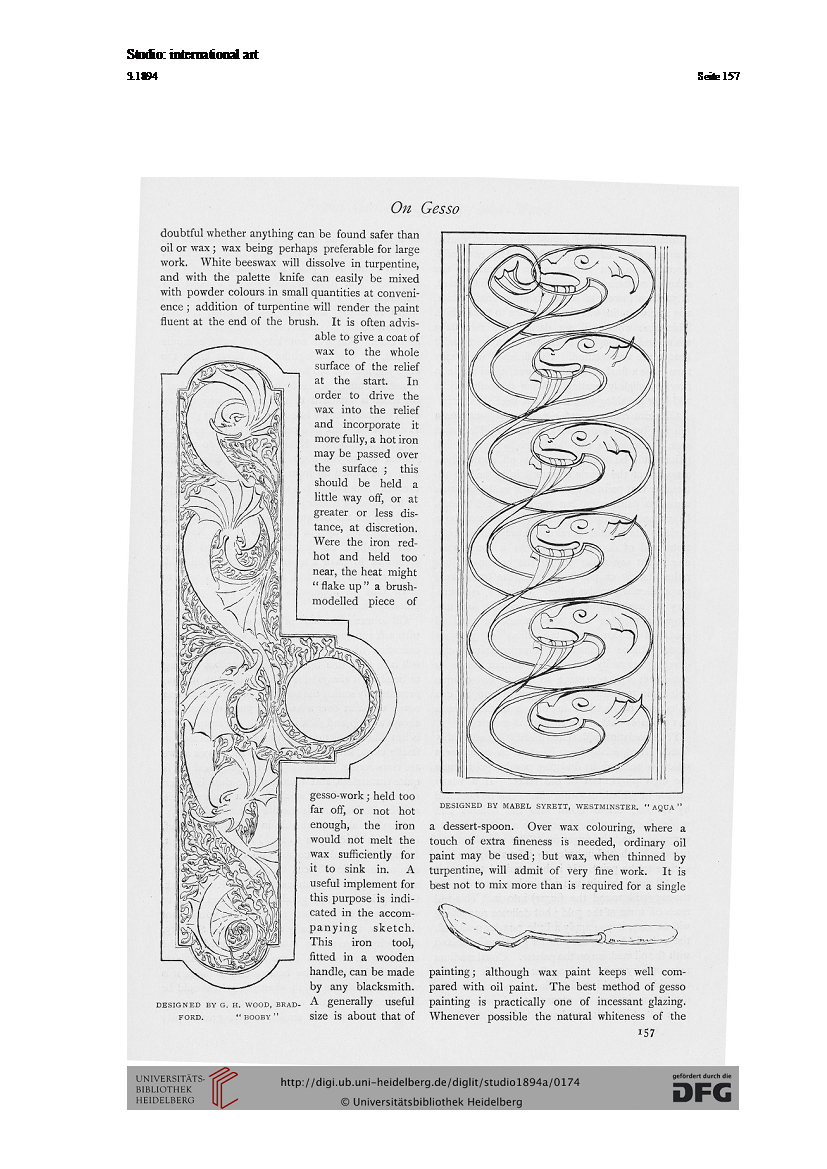

An earlier finger-plate design of Mabel’s entitled Aqua (fig.2), consisting of a striking, repeated pattern reminiscent of the mythical sea creatures by Arts and Crafts ceramicist William De Morgan, appeared in The Studio: An Illustrated Magazine of Fine and Applied Art in January 1894. It is placed alongside a comparable but less prominent design by free thinker George Henry Wood (1847-1945) on a page discussing gesso techniques. Mabel’s swirling, calligraphic design would clearly lend itself well to gesso-work. Mabel is subsequently given an honourable mention for the same design for a cloth book-cover under “Awards in ‘The Studio’ Prize Competitions” in 1896. Mabel’s honourable mentions in leading periodicals The Studio and The Artist reflect the high esteem in which her works were held during the 1890s. These journals aimed to recognise new talent, which often remained obscure, building Mabel’s public profile. An honourable mention in The Studio of 1894 commends a competitive cushion design by Mabel (of Ashley Gardens) titled Pisces: “a clever treatment of fishes, tracing too sketchy for reproduction” (“Awards in the Competition for a Cushion Design,” 149). She receives another honourable mention for a design in The Artist of 1895 (538), listed as the only woman among five award-winning designers. These include famous painter Albert Joseph Moore, Fred Hyland (who illustrated for The Yellow Book and The Savoy ), and Alfred Jones (the artist and engraver of the 1890 Postage stamp featuring US president Thomas Jefferson).

Mabel produced a black-and-white cover design for Aesop’s Fables, illustrating the popular story “The Fox and the Crane,” masterfully manipulating negative space to integrate the stylised title text and fluid animal forms (fig. 3). The fox’s curling tail and tongue, the crane’s looping neck, long pointed beak and black mass of spread wings signify its place in “the Beardsley age” and the art-nouveau style. Another elegant, ornamental crane by Mabel decorates the spine of the book (fig. 3), and these illustrations originally appeared in The Studio of 1896. In Gillon’s Art Nouveau: An Anthology of Design and Illustration from The Studio of 1969, they are placed beside a contemporary but much less imaginative bordered flower design for Robert Southey’s poems by Joseph M. Doran. Doran was an Arts and Crafts designer of international repute, whose textile and wallpaper designs are held by the Victoria & Albert Museum in London. The placement of Mabel’s work alongside Duran’s highlights through contrast her innovative work. Her important contribution to Art Nouveau is displayed in this book, which claims on the back cover to be a selection of “the best and the most typical in Art Nouveau.” Here Mabel Syrett is named along with the likes of Walter Crane (1845-1915), Aubrey Beardsley (1872-1898) and Laurence Housman (1865-1959). Walter Crane, a famous children’s book illustrator, illustrated the Baby’s Own Aesop in 1887, drawing comparable though more naturalistic animals in two scenes for “The Fox and the Crane” to illustrate the moral: “there are games that two can play at” (19).

Mabel married a solicitor, Henry Walter Rydon (1871-1946), born in Middlesex Islington, in the spring of 1901. The 1911 England Census records Mabel and Henry as having been married for 10 years. While Henry’s occupation is listed as “Solicitor,” Mabel’s is left blank, which possibly reflects the decline of her creative career with marriage and motherhood. Mabel and Henry had three children, including Colin and Anthony (the other is omitted from the census records), who became farmers. At the time of the 1911 Census, Mabel’s sister Kate Syrett (single, 37 years old) is listed as a visitor at their home. Netta’s autobiography, The Sheltering Tree , offers further valuable glimpses into Mabel’s life. For example, it details Mabel and Henry’s travels to Italy in 1924, where they took wonderful walks with Netta and their niece, and narrowly avoided a deadly landslide on the Amalfi coast (N. Syrett 247-54).

In later life one of Mabel’s primary interests was the garden of her beautiful Sussex home, Greatham Manor. Here Mabel introduced Netta to her nearest neighbours Alice Meynell (1847-1922), her husband Wilfrid, and their literary family. Alice Meynell’s interests as a professional writer and prominent suffragist chimed with Netta’s. Staying with Mabel in the years before her death gave Netta opportunities to talk to Alice, whose spirituality and rare poetry she admired (N. Syrett 94, 157). Such anecdotes reveal Mabel’s important role in the lives of her sisters, offering a broader picture of the Syrett sisters’ network, and showing how they facilitated one another’s connections. Mabel died a widow at Silver Birches Storrington, Sussex, on 11 February 1961.

©2020, Dr. Lucy Ella Rose, University of Surrey, UK.

Selected Publications about Mabel Syrett

- Baby’s Own Aesop [Aesop’s Fables]. Illustrated by Walter Crane. G. Routledge & Sons, 1887, 19.

- “Bad Art in the Yellow Book.” Review of The Yellow Book , vol. 13, April 1897, New York Times , 17 July 1897, BR5. Yellow Nineties 2.0 , edited by Lorraine Janzen Kooistra, Ryerson University Centre for Digital Humanities, 2019. http://1890s.ca/YB13_review_new_york_times_july_1897/

- British Newspaper Archive

– Dundee Advertiser , Thursday 20 May 1897.

– Leamington Spa Courier, Saturday 25 March 1882, p.4.

– New York Times, 17 July 1897, p.BR5.

– The Cornish and Devon Post, Saturday November 16, 1901.

- 1871 England Census. Ancestry, 2004, https://www.ancestry.co.uk/interactive/7619/KENRG10_994_995-0188?pid=13913964&treeid=&personid=&rc=&usePUB=true&_phsrc=KZV111&_phstart=successSource#?imageId=KENRG10_994_995-0188

- 1891 England Census. Ancestry, 2005, https://www.ancestry.co.uk/interactive/6598/LNDRG12_82_84-0259?pid=11772776&treeid=&personid=&rc=&usePUB=true&_phsrc=KZV114&_phstart=successSource

- 1901 England Census. Ancestry, 2005, https://www.ancestry.co.uk/interactive/7814/LNDRG13_95_97-0256?pid=749254&backurl=https://search.ancestry.co.uk/cgi-

- 1911 England Census. Ancestry, 2011, https://www.ancestry.co.uk/interactive/2352/rg14_00072_0597_03?pid=838961&treeid=&personid=&rc=&usePUB=true&_phsrc=KZV129&_phstart=successSource

- Gillon, Edmund V., ed. Art Nouveau: An Anthology of Design and Illustration from The Studio , 1969, p.36.

- Kooistra, Lorraine Janzen and Dennis Denisoff. “ The Yellow Book: Introduction to Volume 13 (April 1897)” The Yellow Book Digital Edition, edited by Dennis Denisoff and Lorraine Janzen Kooistra, 2014. Yellow Ninties 2.0, General Editor Lorraine Janzen Kooistra, Ryerson University Centre for Digital Humanities, 2019. http://1890s.ca/YB_V13_introduction

- Review of The Yellow Book, vol. 13, April 1897, Academy, 5 June 1897, p. 590. Yellow Nineties 2.0, edited by Lorraine Janzen Kooistra, Ryerson University Centre for Humanities, 2018. http://1890s.ca/YB13_review_academy_june_1897/

- Syrett, Netta. The Sheltering Tree: An Autobiography . London: Geoffrey Bles, 1939.

- The Artist, Photographer and Decorator: An Illustrated Monthly Journal of Applied Art . Wm. Reeves: 1895, vol. 16, p.538.

- “The Yellow Book.” Review of The Yellow Book , vol. 13, April 1897, Literary World , 24 July 1897, p. 245. Yellow Nineties 2.0 , edited by Lorraine Janzen Kooistra, Ryerson University Centre for Digital Humanities, 2019. http://1890s.ca/YB13_review_literary_world_july_1897/

Selected Illustrations by Mabel Syrett

- Syrett, Mabel, Cover of The Yellow Book [cocks in combat], April 1897, vol XIII. Yellow Nineties 2.0 , edited by Lorraine Janzen Kooistra, Ryerson University Centre for Digital Humanities, 2019. http://www.1890s.ca/HTML.aspx?s=YBV13_all.html

- Syrett, Mabel, Aesop’s Fables [‘The Fox and the Crane’], in Art Nouveau: An Anthology of Design and Illustration from The Studio , edited by Edmund V. Gillon, 1969, p.36. The Studio: An Illustrated Magazine of Fine and Applied Art , vol. 2, no. 10, January 1894, p.149. https://digi.ub.uni-heidelberg.de/diglit/studio1894 (accessed 15/04/20); and vol. 8, no. 39, June 1896, pp.54-6.

- Syrett, Mabel, Aqua, finger-plate. The Studio: An Illustrated Magazine of Fine and Applied Art , vol. 3, no. 13, April 1894, p.157.

MLA citation:

Rose, Lucy Ella. “Mabel Syrett (1871-1961),” Yellow Nineties 2.0, edited by Lorraine Janzen Kooistra, Ryerson University Centre for Digital Humanities, 2020, https://1890s.ca/syrett_m_bio/.