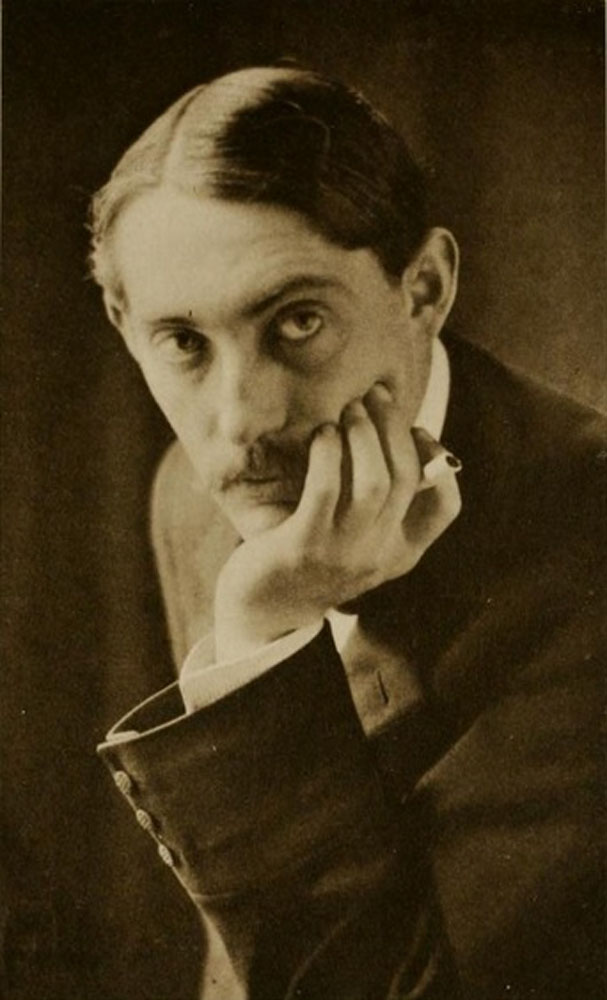

Charles Conder

(1841 – 1896)

Once described as “the painter of pearls, roses and Prince Charming,” Charles Conder was one of the most colourful characters and sensitive talents of the 1890s art world (E.M, 681). Born in London in 1868, he had an unsettled childhood. When he was two years old, his family moved to India, where his father began work as a railway engineer. Following the death of his mother three years later, Charles was sent back to England, where he and his older brother Samuel attended a boarding school in Eastbourne. In 1883, however, Samuel succumbed to tuberculosis, and Charles was sent to New South Wales to train as a land surveyor, under the guidance of his uncle, William Jacomb Conder.

Eighteen months of trigonometrical land surveying proved enough for the young Conder, who was already exploring the possibility of becoming an artist. In 1886, he secured a position at a printers in Sydney and started exhibiting with the Art Society of New South Wales, with whom he also took classes. He was then working in an Impressionistic mode, fostered by frequent plein air excursions with fellow Australian artists. He also contributed black-and-white illustrations to newspapers such as the Illustrated Sydney News and to one-off publications such as Alethea Phillips’s A Romance of the Revolution (1887). Conder often took his illustrative duties lightly, preferring to reflect the mood of a text rather than specific scenes. He would nevertheless draw inspiration from literature throughout his career.

With his work appearing regularly in the Illustrated Sydney News and society exhibitions, Conder soon acquired a reputation as a promising artist, and as a raffish, dandyish personality. Amongst the most important contacts he made during this period were the Australian artist Thomas William “Tom” Roberts (1856-1931), who had trained at the Royal Academy Schools in London, and the Italian Girolamo Nerli (1860-1926), who expanded Conder’s knowledge of contemporary European painting.

In 1888 Conder followed Roberts to Melbourne, home to many of the artists associated with the so-called Heidelberg School, named after the suburb of Heidelberg, where plein air painting was popular. Sharing a studio with Roberts, Conder became an integral figure of this group, which also included Arthur Streeton (1867-1943) and Frederick McCubbin (1855-1917). The “9 by 5 Impression” exhibition, launched in August 1889, proved a turning point for the group, showcasing their particular brand of Australian Impressionism. Conder’s work during this period consisted of loosely painted, sun-baked landscapes, Whistleresque fancies (such as the 1889 How We Lost Poor Flossie), and decorative drawings that owed a certain amount to aestheticism and symbolism, complete with unfurling tendrils, clouds of incense, and (one of Conder’s favourite motifs) blossoming trees.

Following the exhibition, his uncle Henry provided the funds for Conder to study in Paris, where he was based for much of the 1890s. Ostensibly a student at the Académie Julian, and afterwards Fernard Cormon’s, Conder much preferred to receive his education in cafés and cabarets, in the company of like-minded artists. A key friendship of his early years in Paris was fellow Julian student William Rothenstein (1872-1945) who, despite several disagreements, would go on to be one of Conder’s greatest supporters. Though Conder was the more obviously bohemian (drink was already becoming a problem for the artist), both he and Rothenstein attracted the attention of such artists as Henri Toulouse-Lautrec (1864-1901) and Louis Anquetin (1861-1932), with whom they shared a fascination for Montmartre nightlife. Conder immortalised this scene in several works, in particular his 1890 painting The Moulin Rouge (Manchester Art Gallery) and his 1890 drawing A Dream in Absinthe (Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge). The high point of these early years, however, was probably the exhibition he shared with Rothenstein at Père Thomas’s in the Boulevard Malesherbes in 1891, attended by Camille Pissarro (1830-1903) and Edgar Degas (1834-1917).

Conder also sought inspiration outside of Paris, including in Algeria, which he visited from 1891 to 1892, and in various trips into the French countryside, often accompanied by the critic D. S MacColl (an important supporter), Alfred Thornton, and, from 1893, Aubrey Beardsley (1872-1898), with whom Conder would remain close until 1896. Conder was also initiated into Francophile circles based in Dieppe, including Arthur Symons (1865-1945), Ernest Dowson (1867-1900), Walter Sickert (1860-1942) and Oscar Wilde (1854-1900), who described Conder as “very vague and mist-like.” (qtd. in Galbally, Last Bohemian 185). Symons noted that Conder was never a jealous painter, nor a strong conversationalist: he was best known, in fact, for being a “lover of women and wine” ( Confessions, 65-66). Reflecting on correspondence of the time, Rothenstein later commented: “How like Conder his letters were! With a vagueness, a wantonness, a wistfulness all their own” (Vol 1.118).

Never a great self-motivator, friends were undoubtedly important to Conder. So too was literature. Robert Browning (1812-1889) was a continual influence, as were the poems of Omar Khayyam (1048-1131), which were enjoying great popularity at this time. Conder was also inspired by French literature from Villon to Verlaine, with a particular penchant for Balzac (1799-1850), whose heroes he sought to emulate. All of these writers were invoked in his work of the period, which frequently took on a nostalgic air, with its heavily detailed rococo flourishes, flashes of gold paint, cavorting cupids, and keen interest in eighteenth and early nineteenth-century costume. In the mid-1890s, Conder’s work went through significant changes. He began to work on silk and, in 1895, started a series of highly acclaimed designs for fans, which owed something to Watteau. Many paintings of the late 1890s were set into ornate, irregularly shaped frames. He also explored room decoration, the most important example being Nine Painted Panels , his contribution to Siegfried Bing’s second Art Nouveau exhibition in 1896 (now owned by Yale Center for British Art). In the early 1900s, Conder even went in for dress design; this is hardly surprising, since well-dressed women (usually in sumptuous, ballooning dresses) appeared in almost all of his art works at the turn of the century.

Conder’s work is well represented in the pages of The Yellow Book , to which he contributed seven works (see Vols 4, 6, 10, 11, and 13). Though these works differ in medium and finish, they all feature elaborately costumed figures in theatrical, if not fantastical settings. In most cases narratives are suggested, but his characters never appear invested in the roles they are playing. Conder seems content to create an atmosphere. Likewise, though he shares Beardsley’s interest in masked balls, the grotesque, the rococo, and wider aestheticist trends, Conder’s drawings lack the sharp lines and cynical scrutiny of the younger artist’s work. Conder’s art contains sinister undercurrents, undoubtedly, but it is altogether softer, dreamier, and more forgiving than Beardsley’s. As a critic noted in 1901: “Nothing is observed with research, no form is completely realized, no line has structural precision; his drawings are rather in the nature of vague allusions to and reflections upon life” (Anon). Conder’s work also appeared in the first issue of The Savoy, and in Charles Ricketts and Charles Shannon’s magazine The Pageant (published from 1895 to 1897).

At the start of the new century, his reputation enjoyed a sudden ascent, largely due to a series of exhibitions held at the Carfax Gallery in the St. James’ district of London, a new venture founded by Rothenstein and John Fothergill (1876-1957). The size of the gallery and its clientele clearly suited Conder, whose shows were greatly acclaimed by fellow artists and critics alike. Amongst the fan designs and watercolours on silk, he also showed a collection of fascinating lithographs entitled The Balzac Set (1899).

The 1900s not only brought success, but also marriage to the Canadian Stella Maris Belford, with whom Conder settled in Chelsea. The next nine years brought unexpected stability into his life. A return to large-scale oil painting, with a particular leaning towards landscapes (especially beach-scapes) and portraits of rich women, formed the basis of his work, which continued to be widely exhibited (albeit not at the Carfax, with whom he had a not-untypical falling out in 1902). Syphilis cut short his life in February 1909.

Following his death, Conder’s art continued to be positively appraised by contemporaries such as MacColl, Ricketts, and Symons, with Frank Gibson publishing a short book on his life and work in 1913. He was also mentioned in several novels, including Ronald Firbank’s Vainglory (1915) and Arnold Bennett’s The Roll Call (1918). After WWI, however, his reputation suffered a decline. As John Rothenstein noted in his 1938 study: “When under the shock of war, the old order began to dissolve, and all its values called into question, Conder’s art was left stranded” (xv). Despite Rothenstein’s best efforts, Conder was to remain sidelined in all narratives of British art constructed over the course of the twentieth century. When he was recovered, it was by Australian critics: by Ursula Hoff, in the 1970s, and since then by Ann Galbally, whose excellent biography of the artist appeared in 2002, followed by a major exhibition of his work in Sydney, Melbourne, and Adelaide from 2003 to 2004. Conder’s work reappeared as a major component of the 2013 exhibition, Edwardian Opulence, at the Yale Center for British Art, but British scholars continue to overlook him, dismissing his work as fey or insubstantial. There are practical reasons for this neglect: many of Conder’s most delicate paintings have faded over the years and lost their early brilliance. His strengths as an artist, nevertheless, remain perfectly clear – and certainly deserve greater recognition.

© Copyright 2013 Samuel Shaw, Postdoctoral Associate, Yale Center for British Art

Samuel Shaw’s research focuses on the late-nineteenth and early-twentieth century British art world, with a particular interest in the relationship between artists, critics, and the art market. He is currently writing a study of William Rothenstein.

Selected Publications about Charles Conder

- Anon. “Mr. Conder’s Water-Colours.” Athenaeum No.3840 (June 1st, 1901): 701.

- Charles Conder 1868-1909. Sheffield: Graves Art Gallery, 1967.

- Charles Conder 1868-1909. Melbourne: National Gallery of Victoria, 1966.

- Chu, Petra ten-Doesschate. “Siegfried Bing and Charles Conder: The Many Faces of ‘New Art.’” Twenty-First Century Perspectives on Nineteenth-Century Art. Ed. Petra ten-Doesschate Chu and Laurinda S. Dixon. Cranbury: Associated University Presses, 2010.133-149.

- E.M. “The Painter of Pearls, Roses and Prince Charming.” The Academy (November 29 1913): 681.

- Galbally, Ann. Charles Conder: the last bohemian. Melbourne: Miegunyah, 2002.

- Galbally, Ann and Barry Pearce. Charles Conder, 1868-1909 , Sydney: Art Gallery of New South Wales, 2003.

- Gibson, Frank. Charles Conder: his life and work. London: John Lane, 1913.

- Hoff, Ursula. Charles Conder. Melbourne: Lansdowne, 1972.

- MacColl, D. S. “The Paintings on Silk of Charles Conder.” The Studio 13.68 (May 1898): 232-39.

- MacColl, D. S. “Memories of the nineties: two summers with Conder.” London Mercury (November 1938-April 1939).

- Pezzini, Barbara. “New documents regarding the 1902 ‘Fans and other paintings on silk’ exhibition at the Carfax Gallery.” The British Art Journal 13.2 (Autumn 2012): 19-28.

- Ricketts, Charles. “In Memory of Charles Conder.” The Burlington Magazine 15.17 (April 1909): 8-15.

- Rothenstein, John. The Artists of the 1890s. London: Routledge and Sons, 1928.

- – – -. The life and death of Charles Conder, London: Dent, 1938.

- Rothenstein, William. Men and Memories, Vols I & II . London: Faber & Faber, 1931.

- Shaw, Samuel. “British Artists and Balzac at the turn of the twentieth century.” English Literature in Transition 56.4 (2013): 427-44.

- Symons, Arthur. Confessions, London: Haskell House, 1930.

- – – -. Studies on Modern Painters. New York : W.E. Rudge, 1925.

- Trumble, Angus and Andrew Wolf-Rager, eds. Edwardian Opulence . New Haven: Yale UP, 2013.

- Wood, T Martin. “A room decorated by Conder.” The Studio 34 (April 1905): 201-10.

MLA citation:

Shaw, Samuel. “Conder, Charles,” Y90s Biographies , 2013. Yellow Nineties 2.0, edited by Lorraine Janzen Kooistra, Ryerson University Centre for Digital Humanities, 2019, https://1890s.ca/conder_bio/.