TABLE OF CONTENTS

No. 8

Front Cover, by Pamela Colman Smith [i]

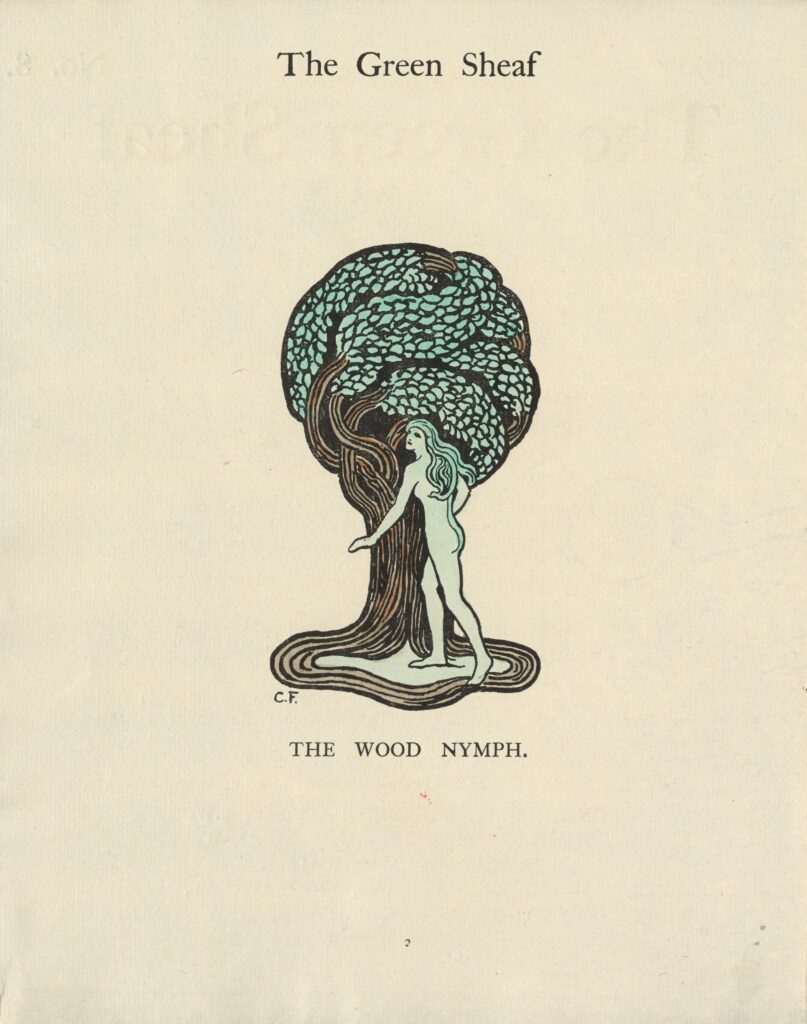

The Wood Nymph, by Cecil French 2

The Wood of Laragh, by Cecil French 3

Page decoration by Pamela Colman Smith 3

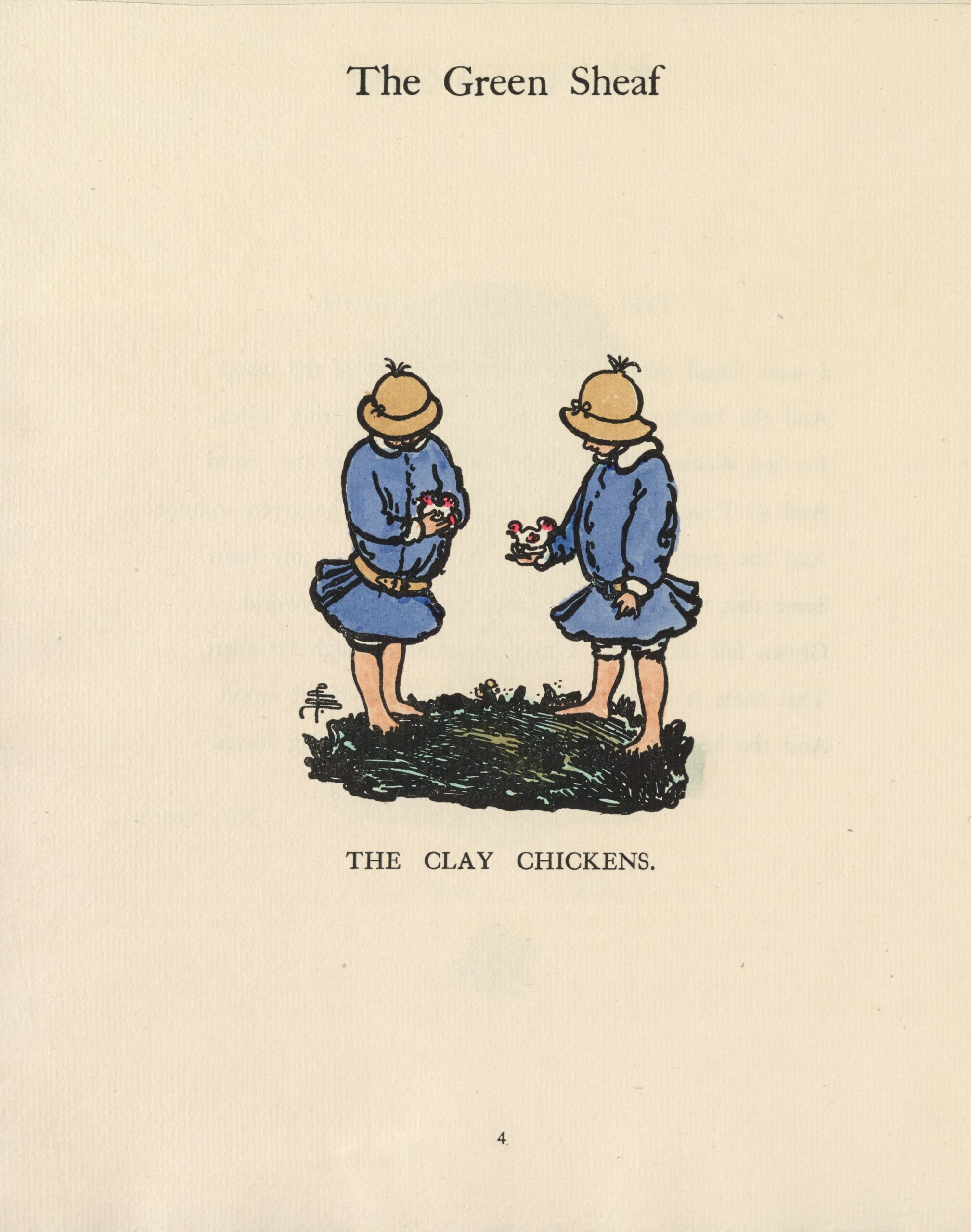

The Clay Chickens, by Pamela Colman Smith 4

The Clay Chickens, by E. Harcourt Williams 5-7

Headpiece illustration by Pamela Colman Smith 5

Tailpiece illustration by Pamela Colman Smith 7

The Gray Coat (A Dream), by Christopher St. John 8-9

Kyn Vyttyn (Before Morning), by L.C. Duncombe-Jewell 10

A Dream, by Victor Bridges 10

The Land of Make-Believe, by Francis Annesley 11

Dawn, by Pamela Colman Smith 11

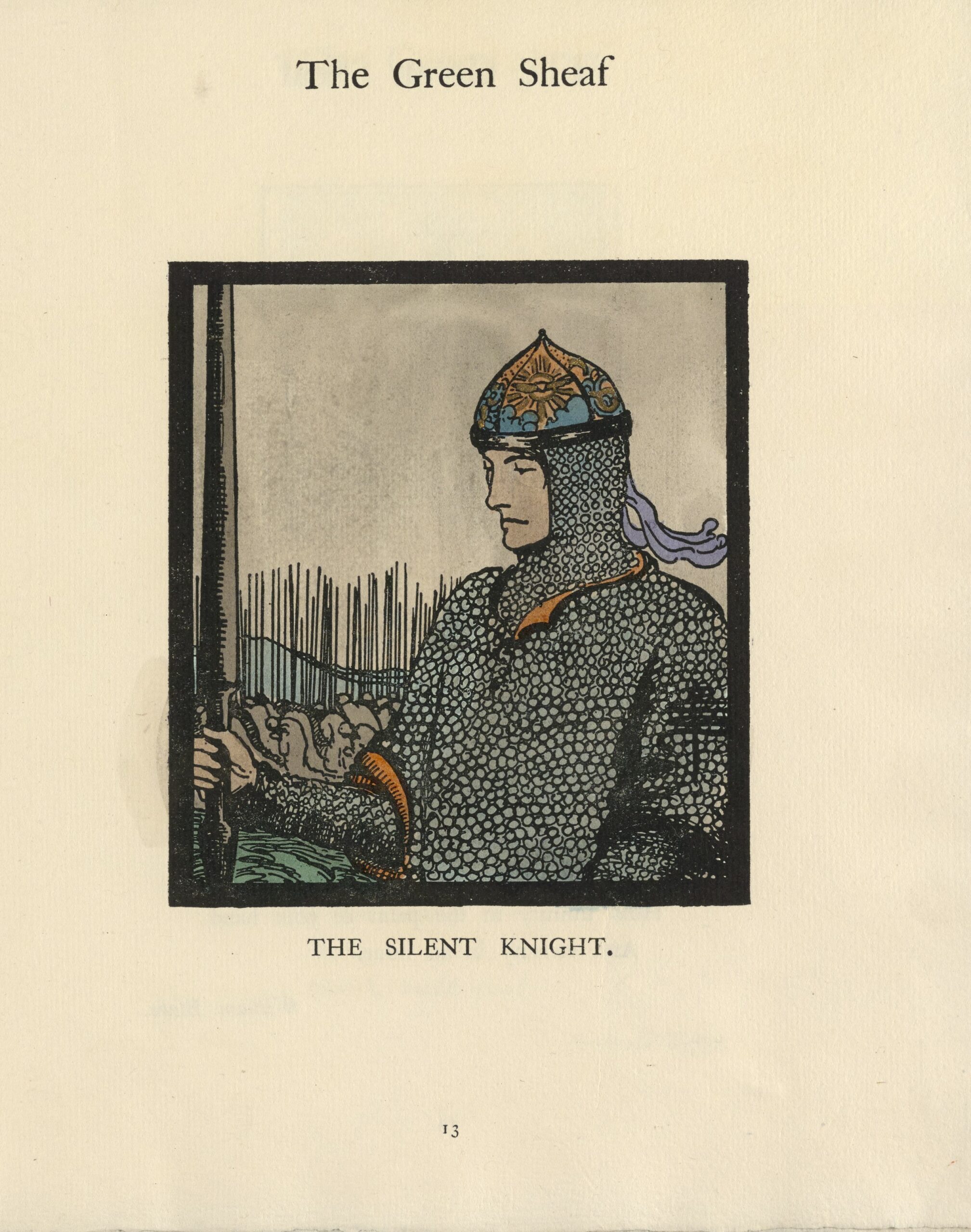

The Knight-Errant, by Alix Egerton 12

The Silent Knight, by Pamela Colman Smith 13

The Definite, by William Blake 14

Illustration by W.T. Horton 14

Belinda, by Reginald Rigby 15

Illustration by Reginald Rigby 15

Advertisements 16

THE WOOD OF LARAGH.

I have found quiet in the hushed twilight of the wood

And the healing of all trouble in the murmuring leaves.

Let me wander till the dusk has hidden away the world

And all I have known, till the silence and the green solitude

And the murmur of the leaves have entered at my heart.

Some day, when dusk has fallen upon me in a world

Grown full of trouble, I may remember, though far apart,

That there is quiet in the hushed twilight of the wood

And the healing of all trouble in the murmuring leaves.

Cecil French.

THE CLAY CHICKENS.

Once upon a time there was an old cheese

maker who had in his care two orphans,

and they all lived in a quiet green valley

high up in the mountains.

Their home was a chalet which stood at the edge of the pine trees. It was

roughly but strongly built of wood, and stained with a rich brown pickle to keep

out the wet.

The orphans, two chubby little boys, were called Philip and Peter. Philip,

the elder by a year, was swarthy like the pines and dark haired, while five-year-old

Peter was as fair as the sun.

One day came toiling up the mountain path that led to the snow beyond,

a traveller—with an enormous white hat. Seeing the old cheese maker busily

churning under the shade of the jutting roof he asked of him a drink of milk.

Whereupon the old peasant went inside, and presently reappeared with some goat’s

milk in a clay bowl, red-glazed and gaily coloured.

The boys who had been playing by the stream that ran down the valley,

came up and eyed—half timidly—half gleefully—the stranger who sat astride the

wood stack that was growing high towards the roof with winter fuel—his wonderful

hat thrown carelessly on the ground. He was looking sad and weary as he glanced

up, but broke into loud laughter at the sight of the barefooted babes in their

blue coats and quaint skull-fitting caps of straw and black velvet with woollen tufts

atop. Children of nature, they were quick to recognise a kindred spirit, and before

long the maker of cheeses left his churning to hold his aching sides and crow

at the unwonted sights he saw.

When evening came the stranger put on his big white hat and swung down

the mountain ; but many were the days he came again, and the boys looked

The Green Sheaf

for his coming with great delight, and he also to finding them. He taught them

games of skill, and how they might waylay the nimble trout. He served them

as a staff for walking, and as a steed for riding. The fine days he beguiled with

play,—the wet with song and story.

Now it so happened, that in spite of all his joy, the stranger was a lonely

man with neither kith nor kindred, and he thought as the autumn drew nigh,

that he would like to take one of the boys to be his son, but such was his love

he could not choose between them. So it befell that on the last day that he came to

see them, ere he went southwards for the winter, he brought with him two

clay money boxes made in the shape of chickens. They were brown in colour

with a blue rosette on the breast and a slit for money in the side. Each side

was also decorated with a design in colour, while the tail was a masterpiece of

the modeller’s art—though little like a tail! He gave one to Philip and one to

Peter who received them with great glee and much lavishing of affection. Then

the man with the hat drew out two silver coins and dropt one into each. For—

thought he—as they use this gift, so shall I be able to judge of their worth.

Whereupon he said farewell to the cheese maker who likewise had a coin—

reluctantly accepted—to slip into the little disused hand-churn that hung beside the

stove and served to keep his frugal store. Then kissing Philip and Peter who

could scarce retain their tears, albeit he promised to come again with the spring,

he went his way.

✱ ✱ ✱ ✱

The snows drew back to their proper and appointed limits on the high

mountains, the fields brought forth their jewels, and the spring came.

Sure enough, too, the man with the white hat came bounding up the mountain

and caught the boys in a long embrace as they stood watching for him by

the stream—now turbid and grey with snow water. When he had shaken the

old peasant by the hand, and drained his bowl of goat’s milk, he sat on the log

stack, small after the winter’s burning, and called Philip and Peter to him.

The Green Sheaf

“Now, Philip, where is your clay chicken?”

Philip, full of a deep mystery, skuttled away and presently returned with a

bundle tied up in a yellow handkerchief spotted with red roses. His baby

fingers fumbled with the knots until suddenly the clay chicken was discovered

shattered in pieces.

The stranger’s eye grew stern. “Why have you done this? Were you so

greedy to get the money?”

“Oh, no! darling Man-with-the-hat. I wanted to give you this—I bought

it of the pedlar yesterday.” The words almost fell over each other with gasps

and spasms of mingled excitement and smiles. He thereupon produced from the

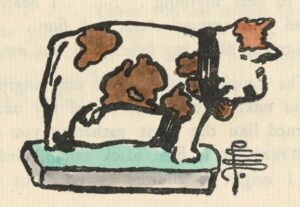

innermost recesses of his garment, a clay cow that stood serenely smiling on a

terra-cotta base that matched her adorning spots.

The stranger turned hurriedly to Peter.

“And yours?”

Peter, the faintest suspicion of self-righteousness gleaming in his eye, displayed

his chicken intact and in perfect condition. The stranger’s face fell. He has kept

it thus—he feared—because he is selfish and would hoard it.

“Oh, Mr. Man-with-the-hat, I wanted to buy you a cow like Philip—(surely

a slip)—but I could not break the chicken because it was so beautiful, and because

you giv’d it me!”

What need is there of more? So glad was the stranger with these answers,

that he took the two fatherless ones to be his sons, and lest the cheese maker might

be lonely, he took him also to be his servant, and they all lived happily ever after.

E. Harcourt Williams.

THE GRAY COAT.

(A Dream.)

ROM my childhood I have been used to dream of fighting.

The clash of swords, the booming of big guns, the rhyth-

mical tramping of feet, the trumpet, the drum, the master

voice of command, the precise movements of many men, the

pageant of uniforms, ragged or grand, the grumbling of veterans,

war songs full of triumph and sadness—this confused mass of sight

and sound is often the background from which emerge dreams

I remember and dreams I forget.

The other night I was in a large cobbled market-place of what seemed a

Flemish town. Together with some other young officers, I was rollicking in

the Square, the object of our merriment being a large and high scaffold in the centre.

We were making wagers about the victims who were walking up a kind of gang-

plank to place their necks under the knife. I remember thinking we were making

too much noise, when a little man in a gray overcoat began to look at me hard

—to my great discomfort. Feeling those eyes upon me, I ceased to enjoy myself,

and I was hardly surprised when someone clapped me on the shoulder, and told

me roughly that it was my turn. “One rash word has done it,” said the little man

in the gray overcoat …. It was Napoleon.

No guards forced you to walk up the steep gang-plank. It was a question of

honour. I had to go, and all I cared about was that I should walk with dignity

and should not move my head about when the time came to place it for the knife

to fall. I felt it depended on me entirely whether the knife made a clean cut or

not …. and I kept very still, for when you are sure that in a minute you will

feel nothing, it is easy to bear anything …. I heard a musical whizz in the

air … my head was severed clean and fine …. and now for the

first time rage and resentment filled my heart. I was not dead.

I stumbled up. The people round seemed very angry that I was not quicker

in making room for the next man. The top of my neck, where my head had

been, throbbed and burned like the worst gathering you ever had on your finger.

The place was red and raw, but it bled black and it bled slowly. In agony and

anguish, I begged that I might be allowed to go down from the scaffold. But

The Green Sheaf

they told me not to be impatient and forced me to stay and watch the others . . .

.

I confess that I now felt some pride at the stillness with which I had met the

knife …. for none of these were still. Their legs twitched, and curled up

like burning feathers as they lay down to place their heads, and they see-sawed

backwards and forwards to such an extent, that the knife made wounds in their

backs, or chopped bits off their hair ….

This horrible sight and my own great pain made me walk but feebly when I

was dismissed from the scaffold …. The crowd roared with laughter as I came

down, and I heard some of them say that I looked funny without my head . . . .

I found refuge in a large empty room with a floor so smooth and so highly polished,

that every picture of its majestic desolation could be seen twice.

There was one bed in the room . . . . I lay down on the floor near it,

hoping that on the icy surface I might find some relief. The man in the bed

stretched out a hand to me, I gripped it and begged him to tell me when I should

be allowed to die . . . .He answered that only one man knew that . . . .

Across the floor stepped that god in the frowsy gray overcoat. I prayed him

that I might die, and that first I might be allowed to write to my mother, for I did

not want her to think worse of me than I deserved.

Napoleon nodded assent with a kind of peremptory irritation …. but

there was nothing small or mean in his impatience.

I followed him into another room, spacious, and furnished with great splendour.

A black servant handed me a quill and I sat down and wrote, nervous because

Napoleon had his eye on me, but determined to be honest …. and not to

cry out …. By this time my headless neck was giving me such torture,

that a cry would have been no great treachery. And I wrote to my dear mother

(who had long been dead) that I had paid the utmost penalty for one rash word,

but that I had kept my head still under the knife, and I hoped she would not

think too badly of me . . . . There was no mercy in Napoleon’s eyes when

I had done, but there was just a fleeting thrill of pride …. and because

it that minute he praised me silently for having kept my head still . . . .

I felt that I had served him, though I was young …. and in great happiness

I began to float upon the viewless wind.

Christopher St. John.

KYN VYTTYN (BEFORE MORNING).

Go back, sweet slip of cambric to my own,

And bid her wait for day:

The night is wet, the windy stars are flown,

The taller trees beside the river moan,

The dawn can be but gray.

Cambric and tears: rain on a soul a-fire:

Dew in the tulip’s heart:

The trampled lane is ankle-deep in mire,

Yet orchard birds, in undesponding quire,

Sing lauds for those who part.

=Go back to her, the light is spreading fast,

Tell her my lips are dumb:

Clouds veil the sun; but say that at the last

Each storm-torn sail and every shaken mast

To some safe port must come.

L.C. Duncombe-Jewell.

4 Mîs Mê, 1903.

A DREAM.

I stood beside my couch, and saw my soul

Radiant, unfettered, beautiful and bright,

Rise from the flesh, and softly steal away

Into the lonely silence of the night.

One glance it cast upon the senseless clay,

In those impassioned eyes I saw the gleam

Of bitter hatred and divine regret;

And cold with fear I woke from out my dream.

Victor Bridges.

THE LAND OF MAKE-BELIEVE.

To thee we turn, O Land of sunny dream,

Kind refuge from a world attuned to grey

With toilsome travail—pleasures reft of play

Where souls go masked and are not what they seem;

But like expectant children at thy door

We stand, and open with love’s golden key,

Nor fear to face the manifold mystery

Of fancy’s realm and read its hidden lore.

Our web of life is woven up with sleep,

Wherefrom but echoes few and faint we bring,

But treasures of our waking dreams we keep

To fill a world-wide space that crowns us king;

Life filches joys—but yet we will not grieve

If we have still our Land of Make-Believe.

Francis Annesley.

DAWN.

Oh come, the woman cried, Oh come with me,

To where the wind-clouds lift the purple sea;

Down from the hills the dawn drives mist away,

And through the forest shoots the glint of day.

THE KNIGHT-ERRANT.

A knight comes riding out of the west,

(De Montfort, De Montfort.)

His armour is bright as steel can be

He carries his pennon waving free.

His device for all the world to see.

(De Montfort, to the rescue.)

“Loyale quand même et loyale toujours”

(De Montfort, De Montfort.)

Three pheons sable upon his shield,

A mailéd arm on an argent field,

A bloody dagger the hand doth wield.

(De Montfort, to the rescue.)

The title he bears is, The Silent Knight,

(De Montfort, De Montfort.)

He won his spurs after long delay.

In the street was he knighted in open day.

By the Lady he loves as she passed that way.

(De Montfort , to the rescue.)

The bravest are those who conquer fear

(De Montfort, De Montfort.)

His quests are many, his victories few,

A coward at heart yet his heart is true,

Can more be said for the bravest of you?

(De Montfort, to the rescue.)

And he rides in the Enchanted Land

(De Montfort, De Montfort.)

He dreams by night and he dreams by day,

And at times he sings on his lonely way

Of the Lady he loves for ever and aye.

(De Montfort , to the rescue.)

Alix Egerton.

BLAKE’S PROPHETIC BOOKS

EDITED BY

A. G. B. Russell & E. R. Maclagan.

JERUSALEM.

Cr. 4to, 6/- net.

A. H. Bullen, 47, Great Russell Street,

London, W.C.

HAND COLOURED PRINTS by Pamela Colman Smith, of

Miss Ellen Terry:—

as “Nance Oldfield” … Price Is. Post free.

as “Meg Page” … … ” Is. ”

as “‘Portia’ hurrying to

the Railway Station” … ” Is. ”

as “Sans Gêne” … … ” Is. ”

as “Queen Katharine” … ” 2s. 6d. ”

as “Mistress Page” … ” 2s. 6d. ”

as “Hiördis” (in the

Vikings) … … … ” 2s. 6d. ”

Subscribers to The Green Sheaf may obtain “Hiördis”

for Is. Post free.

⎯

THE GALLERY,ONE PRINCE’S TERRACE, HEREFORD ROAD,W.

JOHN BAILLIE requests the honour of a visit. Exhibitions every three weeks.

A fine Collection of Modern Jewellery always on view.

Classes for Enamelling, Metal-work, Carving, Bookcasing, Water Colours, Fan

Painting, Wood Engraving, &c.

Gallery open 10.30 a.m. to 6 p.m.

⎯

From ELKIN MATHEWS’ AUTUMN LIST.

THE WINGLESS PSYCHE. (Essays) By Morley Roberts. Author of “Rachel

Marr.” Fcap. 8vo, 2s. 6d. net.

“The writing is supple and sparkling.”—Times.

“Exquisitely written, tinged with philosophic melancholy.”—Vanity Fair.

THE SEASONS WITH THE POETS. An Anthology. Arranged by IDA

Woodward. Pott 4to, 5s. net.

“The wideness of the range adds to the charm of the selections.”—Court Journal.

RECOLLECTIONS OF DANTE GABRIEL ROSSETTI AND HIS CIRCLE.

Cheyne Walk Life. By the late Henry Treffry Dunn. Edited and Annotated by Gale Pedrick,

with a Prefatory Note by W. M. Rossetti. Photogravure and other Illustrations. Cr.

8vo, 3s. 6d. net.

NOTES FROM A LINCOLNSHIRE GARDEN. By A.L.H.A. Cr. 8vo, 3s. 6d.net.

“The writer is evidently a keen observer of nature.”—Morning Post.

“There is a quite particular attraction about this volume.”—Daily News.

THE GOLDEN HELM AND OTHER VERSE. By Wilfrid Wilson Gibson,

Fcap. 8vo, 2s. 6d. net.

“Words and thought move together in noble harmony, and the work is the outcome of

passion and imagination, controlled by a

wise artistic restraint.”—Glasgow Herald.

FIRES THAT SLEEP. By Gladys Schumacher. Cr. 8vo, 3s. 6d. net.

YEATS’ (JACK B.) Plays in the Old Manner, viz., “James Flaunty, or the Terror

of the Western Seas,” and the “ Scourge of the Gulph,” Both illustrated by the Author.

Together with

a miniature presentation plate portrait of R. L. Stevenson, by W. Strang. In a picture

envelope, 2s. net.

A CHRISTMAS GARLAND. Carols by ELIZABETH GIBSON. With Drawings by

EDITH CALVERT. 16mo, 6d. net.

New Volumes in the Vigo Cabinet Series. Royal 16mo, Is. net each.

BALLADS. By John Masefield. Author of “ Salt Water Ballads.”

“Full of that grimness of adventure that comes nowadays to save romance from mere

ethereal dissipations.”—Manchester Guardian.

“Brave ballads with a line swing.”—Academy.

DANTESQUES, a Sonnet Companion to the Inferno. By George A. Greene,

THE LADY OF THE SCARLET SHOES, and other Verses. By Alix Egerton.

⎯

London: ELKIN MATHEWS, Vigo Street, W.

MLA citation:

The Green Sheaf, No. 8, 1903. Green Sheaf Digital Edition, edited by Lorraine Janzen Kooistra. Yellow Nineties 2.0, Toronto Metropolitan University Centre for Digital Humanities, 2022. https://1890s.ca/gsv8_all/