Victoria Cross

[Annie Sophie Cory]

(1868 – 1952)

Victoria Cross (1868-1952) was a British New Woman fiction writer who wove together complex topics such as sexuality, class, race, and gender into her stories and novels. Cross was a prolific writer and after her first short story publications in the mid-1890s, she developed a successful career, publishing more than twenty novels. Despite her international readership, her personal life remained private and mysterious. Cross’s real name was Annie Sophie Cory, but she used many pseudonyms throughout her writing career. She occasionally wrote under the names Victoria Crosse, Vivian/Vivien Cory, and V. C. Griffin (Knapp).

Cross was born in Rawalpindi, India, in 1868 into a family of prolific writers. Cross’s mother was Elizabeth Fanny Griffin (1834-1916); her father, Colonel Arthur Cory (1831-1903), served in the Bengal army, which was part of the British Imperial presence in India. Cross was the youngest of five children; only she and her two older sisters survived to adulthood. In September of 1860 Cross’s brother, Ernest Cory died at three weeks old and her second brother, Harcourt Cory (1862-1863), died at just over a year old in 1863 (Carter 4). Her sisters, Adela Nicolson (1865-1904) and Isabel Cory (1863-1912), both became writers.

Cross’s father, Arthur, had a handful of works published while he was in the military. He served until November 1876, when he retired to pursue his writing career. In 1877 Arthur became a contributor to the Civil and Military Gazette (1872-1963) newspaper in Lahore and later in 1884 he was a part of the Sind Gazette in Karachi. Cross’s older sisters were at a boarding school in London but there is no record of Cross’s attendance. During her childhood, she possibly stayed in India or elsewhere in Europe with her parents or relatives. Further, whether or not Cross had a formal education in her primary years is difficult to determine. Although Cross claimed to have graduated from London University, she failed her examination in 1881 and did not complete her degree (Mitchell). Scholars, such as Charlotte Mitchell, are under the impression that the Cory girls grew up in a socially progressive household, where they were permitted and possibly encouraged to pursue writing careers rather than traditional homemaking roles.

Cross’s sister Adela Nicolson was a well-known erotic poet who wrote under the pseudonym “Laurence Hope.” In 1904, Adela committed suicide due to the grief of losing her husband unexpectedly (Knapp). Cross’s other sister, Isabel Cory, who worked at the Sind Gazette as an editor after their father died, committed suicide in 1912. After her father’s death in 1903, Cross traveled the world with her mother and very wealthy uncle, Heneage Griffin (1848-1939). Following her mother’s death in 1916, Cross would continue to live and travel with her uncle (Mitchell). She had a very close relationship with Griffin and spent the majority of her life by his side. Griffin was also the witness to many of her publishing contracts and he occasionally negotiated with publishers on her behalf.

Cross’s first publication, “ Theodora, a Fragment,” appeared in the fourth volume of The Yellow Book in January 1895. The short story is one of the longest works published in the volume and one of the most provocative. The plot is a tragic love story between the protagonist and narrator, Cecil Ray, and his unconventionally beautiful lover, Theodora. Theodora dresses as a man and tries to seduce Cecil before he leaves on a trip. Despite her androgynous character, he finds himself admiring her features and liberal attitude. Cross’s character Theodora is a portrayal of the New Woman and showcases a new approach to female sexuality and empowerment. The reader is not given a clear understanding of Cecil’s sexual orientation, as there are subtle hints indicating his homosexual past. The ambiguity around homosexuality in the narrative aligns with other queer representations in The Yellow Book (Ledger 18). Laurence Housman’s “ Reflected Faun” in the first volume of this periodical helped establish the motif of androgynous subjects with queer undertones (Housman 117). Cross’s socially outrageous and avant-garde narrative embodies the decadent ambiance that The Yellow Book was so eager to portray.

Cross possibly drew inspiration for “ Theodora, a Fragment” from the life of her sister Adela Nicolson. Adela dressed as a boy to accompany her husband on one of his expeditions to the Zhob Valley in Afghanistan after the couple married in 1890. Further, Adela was known for her eccentric clothing and progressive ideals, similar to Cross’s character Theodora (Marx 234). Adela wrote poetry on topics such as interracial love, cross-dressing, sex, and Hinduism. Though there is little evidence to sustain that Cross had a strong relationship with Adela, their shared writing interests and overlapping literary circles suggest that the sisters kept in contact.

Like most of Cross’s controversial work, “ Theodora a Fragment” was both praised and mocked by reviewers. An article written in the Saturday Review disclosed that the attitude of women like Victoria Cross “is not admirable in any one; in women who write novels it is intolerable” (137). The review further says that “Theodora, a Fragment” is a story “whose object is to represent a girl of fashion characterized by ‘a suggestion of a certain decorous looseness of morals and fastness of manners’… and not [written] for any finesse of art” ( The Saturday Review 137).

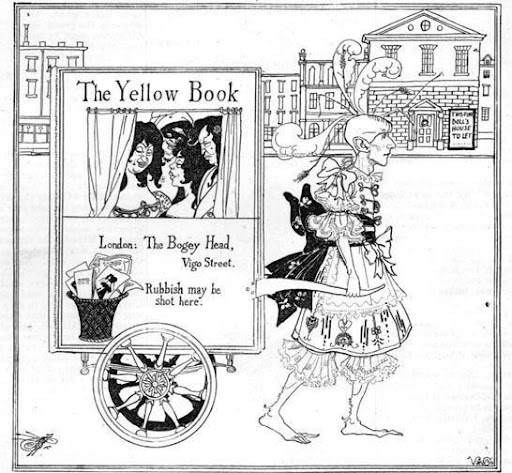

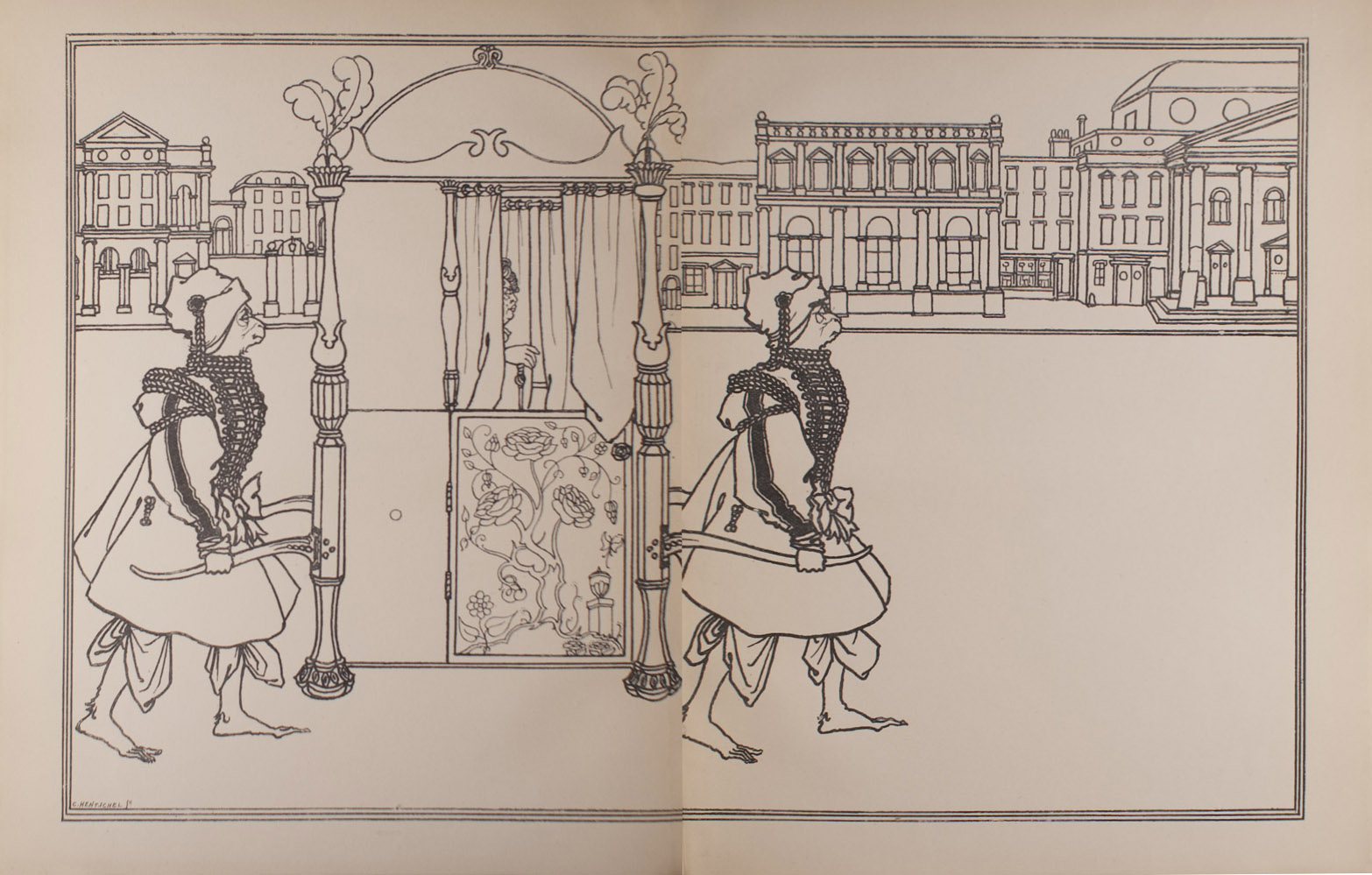

Cross received further criticism on “ Theodora, a Fragment” in Punch, in an article written by Ada Leverson. The title, “Tooraloora a Fragment,” satirizes Cross’s short story and the accompanying caricature ridicules The Bodley Head Publishing House (fig. 1). The article includes lines of dialogue between an English man and woman, similar to Cross’s story. However, the lines are sarcastic and crude, portraying Tooraloora as a derelict prostitute Leverson 58). The drawing attached to the article mocked the fourth volume of The Yellow Book with an outlandish caricature of Aubrey Beardsley ’s “ Frontispiece for Juvenal” (fig. 2)

“ Theodora, a Fragment” was the third chapter of Cross’s novel, Six Chapters of a Man’s Life, which was not published until 1903. In 1894, Cross sent John Lane (1854-1925) and Henry Harland (1861-1905) the manuscripts for both Different Views and The Refiner’s Fire, the initial title of the Six Chapters of a Man’s Life (Mitchell). Different Views was later published without a title as the second work in the 1906 collection, Six Women . Lane was hesitant to publish Cross’s work, thinking the texts were too scandalous in their frank approach to sex. However, Harland strongly advocated that a chapter of The Refiner’s Fire be published in The Yellow Book. In a letter to Lane on November 22 1894, Harland writes:.

My dear Lane, “The Refiner’s Fire” is —tout simplement—a work of genius. And I am not sure that its genius isn’t proved, if possible, more by its defects than by its qualities…. Now, as to the question of publishing it. It seems to me a great pity that it should not be published, a great pity that it should be lost to the world…. Yet, do you know, if I were a publisher, I shouldn’t hesitate an instant. (Beckson and Lasner 417)

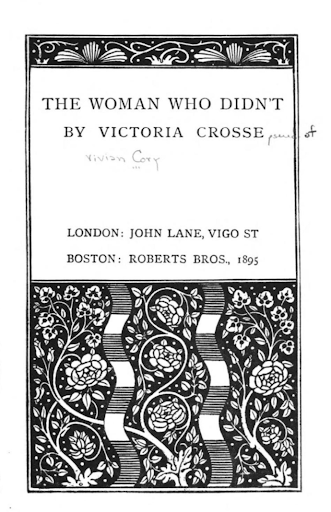

Harland managed to convince Lane that Cross’s work was indeed aligned with The Yellow Book. Just a few months after Cross published “Theodora, a Fragment,” Lane published her novel, The Woman Who Didn’t (Mitchell). Her novel was part of Lane’s “Keynote” fiction series, which consisted of a combination of short stories and novels in thirty-three volumes. The series was published between 1894 and 1897 out of Lane’s Bodley Head Press (W. Harris 1407). Among the first few publications in the series was Grant Allen’s The Woman Who Did in February 1895 (Morton 148). Allen’s novel, “condemned as hideous and repulsive, deals with a woman’s decision to live with a lover in free union,” whereas “Cross’s The Woman Who Didn’t has as its subject not the legitimacy of marriage itself but allegiance to a preexisting commitment” (Knapp). Cross’s direct reply to Grant’s novel only four months later embodied the controversial and self-reflexive avant-garde nature that the Bodley Head Press represented. Cross presented her work at the Bodley Head alongside other New Women writers, including George Egerton (1859-1945), Netta Syrett (1865-1943), Evelyn Sharp (1869–1955), and Olive Custance (1874-1944) (Knapp). Many writers from Lane’s “Keynote” series, including Cross, were also published in The Yellow Book . Aubrey Beardsley (1872-1898) designed the title page and cover for Cross’s novel in Lane’s “Keynote” series using his famous black-ink style (fig. 3).

The Bookman wrote in August of 1895 that Victoria Cross “lives in the country near London” (“The Bookman” 11), which meant that despite her peripatetic life, she resided close to metropolis during the period when Lane was her publisher. Cross led a secluded lifestyle, which was facilitated by her international travels, various pseudonyms, and desire to be excluded from social circles. She rarely frequented literary events, and she did not engage with other authors very often (Knapp). Ella D’Arcy, a Yellow Book contributor and sub-editor, wrote in a brief autobiographical account: “I recall Victoria Cross, with a white face, thick lips, and tightly-curling tow-coloured hair” (Ledger 18). This is one of the few intimate accounts of the otherwise mysterious writer. According to Frank Harris, Oscar Wilde (1854-1900) quipped that “if one could only bed Thomas Hardy with Victoria Cross, he would have had some real light with which to show off his little keepsake pictures of starched ladies” (F. Harris 477). Cross’s sister, Adela Nicolson, was friends with Thomas Hardy and the Crackanthorpe family. Adela attended a London literary salon in 1903 with Hardy (1840-1928) and another Yellow Book contributor, Hubert Crackanthorpe (1870-1896) (Marx 234). Cross possibly accompanied her sister to social events and might have also been acquainted with the Crackanthorpes.

Blanche Crackanthorpe (1847-1928), Hubert’s mother, was a feminist campaigner and hostess of a literary salon who wrote an article entitled “Sex in Modern Literature” in The Nineteenth Century in which she referenced Cross’s work. Crackanthorpe stated that it was unfair that women like the enigmatic author of “Theodora” were often blamed for society’s moral decline. She writes, “instead of walking on the mountain tops, breathing in the pure high atmosphere of imagination freely playing around the truths of life and love…they force [women] down into the stifling charnel-house… it is the fashion of the hour to cry that women are the chief offenders…Whilst male authors proudly produce such [erotic] books… it is unjust to throw the greater blame on the [female] writers” (Crackanthorpe 614). Crackanthorpe articulated similar beliefs in her article “The Revolt of the Daughters,” in which she criticizes Victorian gender roles and advocates for women’s rights to an education (Rubinstein). Crackanthorpe’s description of the challenges faced by New Woman writers suggests one reason Cross may have desired to remain unidentified and hidden from the public.

Cross’s entry into the literary sphere through The Yellow Book and Keynote series was only the start of her prosperous writing career. Lane did not publish her following novels, likely because he thought they were too sexually suggestive after the Oscar Wilde scandal in the spring of 1895 (Mitchell). However, Cross maintained a respectable literary reputation until she signed with Walter Scott (1826-1910), a known erotic publisher, who published Paula in 1896 and A Girl of the Klondike in 1899.

A pivotal moment for Cross’s career came in 1901, when she published Anna Lombard. The novel sold six million copies and was translated into multiple languages. Anna Lombard told the story of a woman who was having a secret affair. In the narrative, Cross reversed traditional roles and characterized the female protagonist as sexually adventurous. In contrast, the men were portrayed as sexual objects for Anna’s pleasure. The moral panic brought on by Anna Lombard shook readers all over the globe. Cross’s scandalous novel was characterized as indecent and corrupt. She fought against the ban of her novel in a New Zealand court case (Mitchell). While many praised her work, her erotic writing prompted some critics to slander her in the press. Regardless of the backlash, her novels rose in popularity and sales. Her success indicates that despite her sexually taboo content, many were actively reading her books.

Cross published Six Chapters of a Man’s Life, formerly titled The Refiners Fire, in 1904. For her next novel, Cross pitted two British publishers, T. Werner Laurie (1866-1944) and John Long against one another, telling each that the other had offered her a better deal for Six Women in compensation and royalties. Her uncle Griffin advocated on her behalf with Long, but in July of 1905 Cross signed with T. Werner Laurie for the publication of Six Women (Mitchell). In letters exchanged between Cross and Laurie, Cross was professional but also adamant about her value as an established novelist. Unfortunately, Cross’s old agent, Hughes Massie, had sent the manuscript for Life’s Shop Window to Mitchell Kennerley without a contract. Kennerley then sold copies of Cross’s book without paying her royalties. The battle of making claims to the novel’s fortune would be dragged out for almost a decade.

Four of Cross’s novels— Life’s Shop Window, Five Nights, Paula, and The Night of Temptation —were turned into films in the 1910s. Cross wanted to adapt her novels as plays and was introduced to the famous dramatist, Reginald Golding Bright (1875-1941). Bright was the husband of George Egerton, the original “Keynotes” author. Unfortunately, Bright rejected the dramatization of her novel The Greater Law and it was not until 1920 that the play was finally produced. In 1917, when Cross dramatized her novel Five Nights, producers deemed the play unfit for public performance. However, Cross was convinced the piece would be a success based on the popularity of the film, and with revisions the play was produced in 1918. She had a long-lasting working relationship with Herbert Thring (1859-1941) from the Society of Authors and they exchanged many letters between the years of 1910 and 1920 (Mitchell). Thring was a confidant of Cross, and she often shared her publishing struggles with him and asked him for business or legal advice.

Over the years Cross travelled between North America, Europe, and India, living in lavish hotels with her uncle. Her stories also crossed borders, with book reviews about her novels, plays, and films published all around the world, from the Times of India to the Washington Post (Dierkes-Thrun 205). She published Jim, her last book, in January of 1937 at the age of 69, but by then her book advances were reduced by half and her fame had slowly subsided.

Cross mentioned to her cousin in 1943 that she was in love with an American but for the most part her personal life remains unknown. She never married or publicized any relationships (Mitchell). Her secluded personal life is rather bewildering, so little is documented about her friendships and love interests; it is difficult to imagine how the prolific romantic and sexual topics she explores in her writing came to fruition. When Cross died in 1952 in Milan, she left her estate to her dear friend Paolo Tosi. Malcolm Nicolson (1900-1979), Adela Nicolson’s only child, accused Tosi of manipulating Cross for her and her uncle’s remaining estate. However, Tosi argued that following the death of Griffin in 1939, he was there for Cross when she fell into a depression and struggled with suicidal thoughts (Mitchell).

Cross succeeded at concealing her identity well for a writer who produced dozens of popular works and was frequently targeted by the media. She remained largely unseen, with the exception of a handful of personal accounts from fellow Yellow Book contributors. Cross and her works received increased academic attention during the late 1990s when Shoshana Knapp published the first biography on Cross and analyzed her texts. Knapp’s biography paved the way for Charlotte Mitchell’s extensive and recent biographical research on Cross. Cross’s contributions to the New Woman’s movement are substantial and her work is now being analyzed by many scholars through feminist, queer, and postcolonial lenses.

©2021, Helena Wright, Ryerson University, Toronto, Canada.

Selected Publications by Victoria Cross

- “Theodora, a Fragment.” The Yellow Book, vol. 4, January 1895, pp. 156-188. Yellow Book Digital Edition, edited by Dennis Denisoff and Lorraine Janzen Kooistra, 2010-2014. Yellow Nineties 2.0, Ryerson University Centre for Digital Humanities, 2019. https://1890s.ca/YBV4_cross_theodora/

- The Woman Who Didn’t. London, Lane, 1895. (Boston, Roberts, 1895).

- Paula: A Sketch from Life. London, Scott, 1896. (New York, Munro, 1898).

- A Girl of the Klondike. London, Scott, 1899. (New York, Macaulay, 1899).

- Anna Lombard. London, Long, 1901. (New York, Kensington, 1902).

- Six Chapters of a Man’s Life. London, Scott, 1903. (New York, Kennerley, 1908).

- To-morrow? London, Scott, 1904. New York, Macaulay, 1904. (New York, Kennerley, 1908).

- The Religion of Evelyn Hastings. London, Scott, 1905. (New York, Kennerley, 1908).

- Life of My Heart. London, Scott, 1905. (New York, Macaulay, 1915).

- Six Women. London, Laurie, 1906. (New York, Kennerley, 1906).

- Life’s Shop Window. London, Laurie, 1907. (New York, Kennerley, 1907).

- Five Nights. London, Long, 1908. (New York, Kennerley, 1908).

- The Love of Kusuma: An Eastern Love Story, as Bal Krishna . London, Laurie, 1910.

- The Eternal Fires. London, Laurie, 1910. (New York, Kennerley, 1910).

- Self and the Other. London, Laurie, 1911. (New York, Hewitt, 1911).

- The Life Sentence. London, Long, 1912. (New York, Macaulay, 1914).

- The Night of Temptation. London, Laurie, 1912. (New York, Macaulay, 1914).

- The Greater Law. London, Long, 1914. (New York, Macaulay, 1914).

- Daughters of Heaven. London, Laurie, 1920. (New York, Brentano, 1920).

- Over Life’s Edge. London, Laurie, 1921. (New York, Brentano, 1921).

- The Beating Heart. London, Daniel, 1924. (New York, Brentano, 1924).

- Electric Love. London, Laurie, 1929. (New York, Macaulay, 1929).

- The Unconscious Sinner. London, Laurie, 1930. (New York, Macaulay, 1930).

- A Husband’s Holiday. London, Laurie, 1932.

- The Girl in the Studio: The Story of Her Strange, New Way of Loving . London, Laurie, 1934.

- Jim. London, Laurie, 1937.

Selected Publications Referring to Victoria Cross

- “Adela Florence Cory Nicolson.” Gale Literature: Contemporary Authors , Gale, 2003. Gale Literature Resource Center .

- Beardsley, Aubrey. “Frontispiece for Juvenal.” The Yellow Book , vol. 4, 1895, pp. 288-289. Yellow Book Digital Edition , edited by Dennis Denisoff and Lorraine Janzen Kooistra, 2011-2014. The Yellow Nineties 2.0, Ryerson University Centre for Digital Humanities, 2020, https://1890s.ca/yb4-beardsley-juvenal/

- Beckson, Karl, and Mark Samuels Lasner. “ The Yellow Book and Beyond: Selected Letters of Henry Harland to John Lane.” English Literature in Transition, vol. 42, no. 4, 1999, pp. 401–405.

- The Bookman, New York, Aug. 1895, p. 11. https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=uva.x000280677&view=1up&seq=23/

- Carter, Jennifer. “Colonel Arthur Cory,” Kipling Society of Australia , 1994.

- Crackanthorpe, Blanche. “The Revolt of the Daughters,” Nineteenth Century, vol. 35, 1894, pp. 23-31

- —. “Sex in Modem Literature.” The Nineteenth Century , April 1895, pp. 607-616 https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=mdp.39015019134702&view=1up&seq=634/

- Deirkes-Thrun, Petra. “Victoria Cross’s Six Chapters of a Man’s Life: Queering Middlebrow Feminism.” Middlebrow and Gender 1890-1945, edited by Christoph Ehland and Cornelia Wächter, Rodopi, 2016, pp. 202–227, doi:10.1163/9789004313378_012.

- Grundy, Isobel. “Victoria Cross.” Orlando: Women’s Writing in the British Isles from the Beginnings to the Present , Cambridge, 2006. http://orlando.cambridge.org.ezproxy.lib.ryerson.ca/protected/svPeople?formname=r&person_id=crosvi&subform=1

- Harris, Frank. Oscar Wilde: His Life and Confessions . vol. 2, Book Jungle, 2010.

- Harris, Wendell V. “John Lane’s Keynotes Series and the Fiction of the 1890’s.” Publications of the Modern Language Association of America , vol. 83, no. 5, Oct. 1968, pp. 1407–1413. JSTOR, doi:10.2307/1261313.

- Housman, Laurence. “The Reflected Faun.” The Yellow Book , vol. 1, 1894, p. 117. Yellow Book Digital Edition , edited by Dennis Denisoff and Lorraine Janzen Kooistra, 2011-2014. Yellow Nineties 2.0, Ryerson University Centre for Digital Humanities, 2020, https://1890s.ca/yb1-housman-faun/

- Knapp, Shoshana Milgram. “Victoria Cross.” Dictionary of Literary Biography Late-Victorian and Edwardian British Novelists: Second Series , edited by George M. Johnson, vol. 197. Gale Literature Resource Center, 1999.

- Ledger, Sally. “Wilde Women and The Yellow Book: The Sexual Politics of Aestheticism and Decadence.” English Literature in Transition, 1880-1920 , vol. 50, no. 1, 2007, pp. 5–26. roject MUSE , doi:10.1353/elt.2007.0007.

- Leverson, Ada. “From the Queer and Yellow Book.” Punch, 2 Feb. 1895, pp. 58. https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=mdp.39015055218641&view=1up&seq=66

- Marx, Edward. “Reviving Laurence Hope.” Women’s Poetry, Late Romantic to Late Victorian , 1999, pp. 230–242. Springer Link, doi:10.1007/978-1-349-27021-7_11.

- Mitchell, Charlotte. “Victoria Cross.” Victorian Fiction Research Unit , School of English, Media Studies and Art History, Univ. of Queensland, 2002. https://victorianfictionresearchguides.org/victoria-cross/

- Morton, Peter. Busiest Man in England: Grant Allen and the Writing Trade 1875-1900. Palgrave Macmillan, 2016.

- Saturday Review of Politics, Literature, Science and Art , London Vol. 79, 26 Jan. 1895, pp. 137-138. https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=hvd.32044092859404&view=1up&seq=155

- Rubinstein, David. “1894: English Women protest: The Revolt of the Daughters and the New Woman.” Protest and Punishment. Presses Universitaires François-Rabelais, 1984, pp. 29-43. doi:10.4000/books.pufr.4403.