BETWEEN the twelfth and the six-

teenth century nearly every country

in Europe possessed some sort of a

religious drama, which in many cases

has lingered on, nearly or quite, to

the present day. Even in England—

in Yorkshire, in Dorset and Sussex,

and perhaps in other counties—the

old Christmas play of St. George and

the Dragon is not quite extinct,

though in its latter days its action

has been rendered chaotic by the

introduction of King George III.,

Admiral Nelson, and other national

heroes, whose relation to either the

Knight or the Dragon is a little

difficult to follow. The stage directions, which are fairly numerous

in most of the old plays which have been preserved, enable us to

picture to ourselves the successive stages of their development with

considerable minuteness. In some churches the ‘sepulchre’ is still

preserved to which, in the earliest liturgical dramas, the choristers

advanced, in the guise of the three Maries, to act over again the scene

on the first Easter-day; while of that other scene, when at Christmas the

shepherds brought their simple offerings, a cap, a nutting stick, or a

bob of cherries, to the Holy Child, a trace still exists in the representa-

tion, either by a transparency or a model, of the manger of Bethlehem,

still common in Roman Catholic churches, and not unknown in some

English ones. When the scene of the plays was removed from the

THROUGH the green boughs, I hardly saw thy face

They twined so close ; the sun was in mine eyes ;

And now the sullen trees in sombre lace,

Stand bare beneath the sinister, sad skies.

O sun and summer ! Say, in what far night,

The gold and green, the glory of thine head,

Of bough and branch have fallen ? O, the white,

Gaunt ghosts that flutter where thy feet have sped,

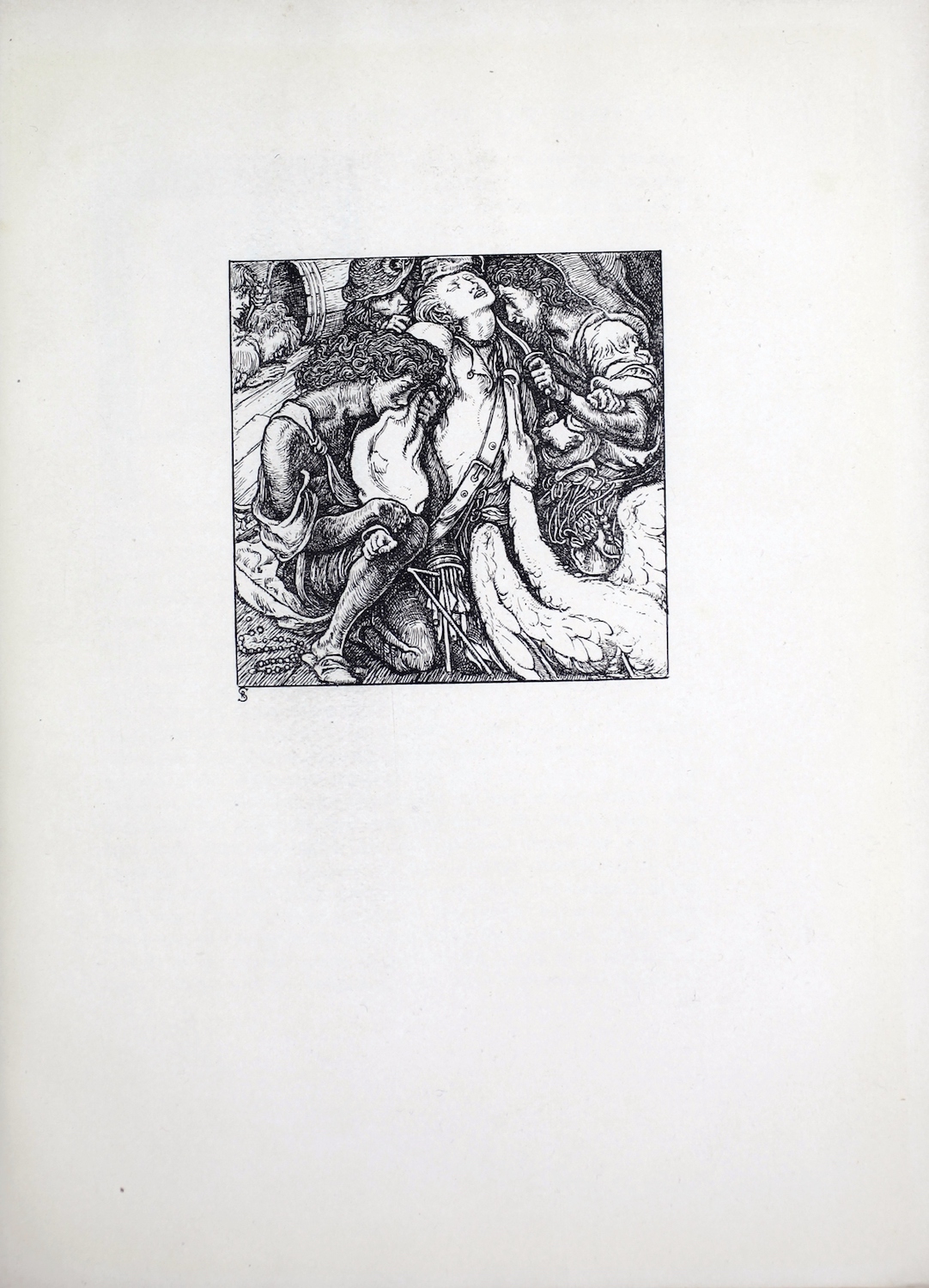

and the fact re-

mains that in only

one country, and

practically only

in one city in that

country (for the

Sienna editions

are merely re-

prints) did the

religious plays,

which in one

form or another

were then being

acted all over

Europe, receive

any contempor-

ary illustration.

This one city was

Florence; and

alike for the

special form in

which the re-

ligious drama

was there de-

veloped, for the causes which contributed to its popularity at the turn of

the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, and for its close connection with

the popular art of the day, the subject is one of considerable interest.

On its literary and religious side, the late John Addington Symonds dis-

cussed it in Studies of the Italian Renaissance with his usual ability,

and many of the plays have been reprinted by Signor Ancona. Of late

years the little pictures by which they are illustrated have also received

attention, a fact amply attested by the extraordinary rise in their

market value. But it is worth while to bring together, even if only in

outline, the pictures and the plays to which they belong, more closely

than has hitherto been attempted, and this is my object in the present

paper.

Across the terrace, that is desolate,

But rang then with thy laughter : ghost of thee,

That holds its shroud up with most delicate

Dead fingers ; and, behind, the ghost of me,

Tripping fantastic with a mouth that jeers

At roseal flowers of youth, the turbid streams

Toss in derision down the barren years

To Death, the Host of all our golden dreams.

nothing for now.

MLA citation:

Dowson, Ernest. “Saint-Germain-En-Laye 1887-1895.” The Savoy, vol. 2 April 1896, pp. 173-183. Savoy Digital Edition, edited by Christopher Keep and Lorraine Janzen Kooistra, 2018-2020. Yellow Nineties 2.0, Ryerson University Centre for Digital Humanities, 2019. https://1890s.ca/savoyv2-dowson-saint